Introduction: Approximately 70-80% of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the skin is composed of collagen, primarily types I & III[1]. Following injury, damaged collagen attracts inflammatory cells, succeeded by fibroblasts and keratinocytes to the dermal wound, aiding in debridement, angiogenesis and re-epithelialization, respectively[2]. Given its prominent role in wound healing, collagen has been widely used in commercial tissue engineering and chronic wound care products. In particular, collagen dressings in wound care vary in the preservation of native ECM, ranging from intact ECM to gelatin[2],[3]. The thermal and structural properties of eight commercially available collagen wound care dressings were explored using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). DSC has historically been used to demonstrate the effects of greater tissue processing in lowering the onset of melting temperature (To) of regenerative surgical scaffolds[4], but its use in comparing wound dressings is novel.

Materials and Methods: DSC. Samples of CollaSorb (CS; N=45; Hartmann) , Endoform Dermal Template (EDT; N=45; Hollister Incorporated), Promogran, Promogran Prisma (Pr and PrPr; N=45 each; Systagenix), Puracol and Puracol Plus (P & PP; N=45 each; Medline), Fibracol Plus (FP; N=15; Systagenix), and Skin Temp II (ST; N=15; Human Biosciences) were hydrated in phosphate buffered saline, hermetically sealed in crucibles, and heated. In a preliminary survey, a scan from 2-125˚C was performed on the first N=5 from each group. The remaining samples in each group of dressings were scanned from 5-85˚C. All DSC scans were performed at 1˚C/min. Thermograms were analyzed using linear method to determine the To of each sample. SEM. Cross-sections and both sides of dry samples of each collagen dressing were imaged at 250, 500, & 1000X. TEM. EDT and Pr were hydrated, serially dehydrated and fixed then embedded in Spurr resin prior to imaging at 3524, 6523, & 12,114X.

Data Analysis: A nested ANOVA was performed to compare average To across dressings. Tukey’s post hoc test and an F-test were used to identify significant differences between dressings and within lots of each dressing, respectively.

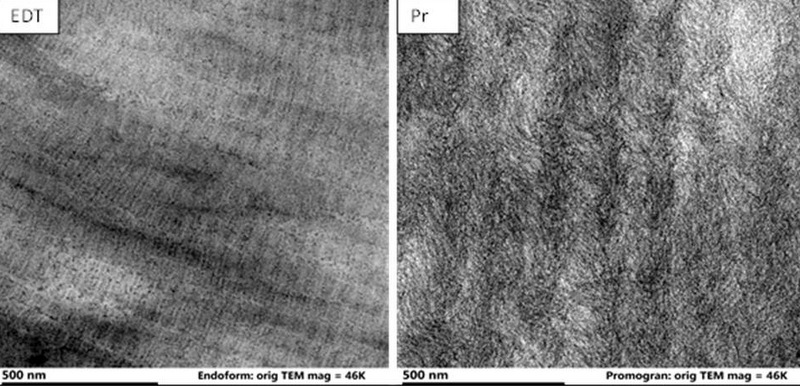

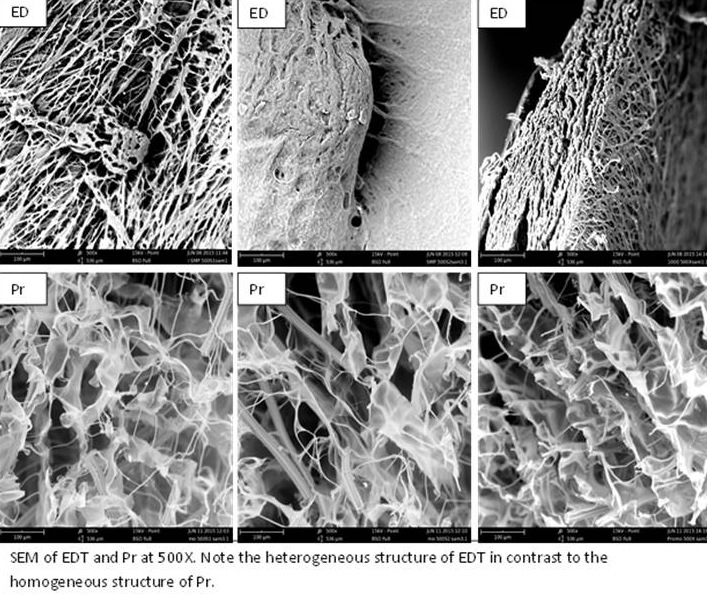

Results: Overall mean To ± std dev for the groups were CS: 43.26±1.3; EDT: 58.68±1.7; Pr: 35.64±1.3; PrPr: 35.05±1.0; P: 41.35±2.8; PP: 41.64±3.7; FP: 36.18±0.4; & ST: 36.33±0.7°C, with EDT differing significantly from the other dressings (p<0.001). SEM showed preservation of native ECM sidedness in EDT, while all other dressings appeared homogeneous across surfaces. TEM confirmed the presence of native collagen banding periodicity of ~65nm[5] in EDT, which was lacking in Pr.

Discussion: Collectively these DSC and SEM data demonstrate greater preservation of native ECM properties in EDT in comparison to the other dressings studied. TEM data confirmed these differences between EDT and Pr. While the impact of these thermal and structural differences on clinical performance are unknown, the retention of native ECM properties has been hypothesized to correlate to the observation of broader in vitro inhibition of proteases by EDT over Pr[3].

This work was funded by Hollister Incorporated

References:

[1] Oikarinen A & Knuutinen A (2002). Mechanical Properties of Human Skin: Biochemical Aspects. In Bioengineering of the Skin, Vol 5: Skin Biomechanics. Elsner P ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

[2] Westgate S, Cutting K, DeLuca G, & Asaad K (2012). Collagen dressings made easy. Wounds UK, 8(1), 1-4.

[3] Negron L, Lun S, & May B (2012). Ovine forestomach matrix biomaterial is a broad spectrum inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases and neutrophil elastase. Int Wound J, 392-397.

[4] Sun WQ, Xu H, Sandor M, & Lombardi J. (2013). Process-induced extracellular matrix alterations affect the mechanisms of soft tissue repair and regeneration. Journal of Tissue Eng, 4: 1-12.

[5] Yannas I (2004). Chapter 2.8 Natural Materials. In Biomaterials Science, Second Edition: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine. Ratner BD, Allan S. Hoffman AS, Schoen FJ, Lemons JE. San Diego: Academic Press.

[6] Cullen B, Watt PW, Lundquist C, Silcock D, Schmidt RJ, Bogan D, Light ND. (2002) The role of oxidised regenerated cellulose/collagen in chronic wound repair and its potential mechanism of action. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 34(12): 1544-56.