- 1Doctorate in Agricultural Sciences, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia (FMVZ) Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz, Mexico

- 2Irapuato Unit, Department of Biotechnology and Biochemistry, Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute (CINVESTAV-IPN), Irapuato, Mexico

- 3Medicinal Chemistry and Chemogenomics Laboratory, Facultad de Bioanálisis, Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz, Mexico

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), often referred to as nature’s antibiotics, are ubiquitous in living organisms, spanning from bacteria to humans. Their potency, versatility, and unique mechanisms of action have garnered significant research attention. Unlike conventional antibiotics, peptides are biodegradable, adding to their appeal as potential candidates to address bacterial resistance in livestock farming—a challenge that has been under scrutiny for decades. This issue is complex and multifactorial, influenced by a variety of components. The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed a comprehensive approach known as One Health, emphasizing the interconnectedness of human-animal-environment relationships in tackling such challenges. This review explores the application of AMPs in livestock farming and how they can mitigate the impact of this practice within the One Health framework.

Introduction

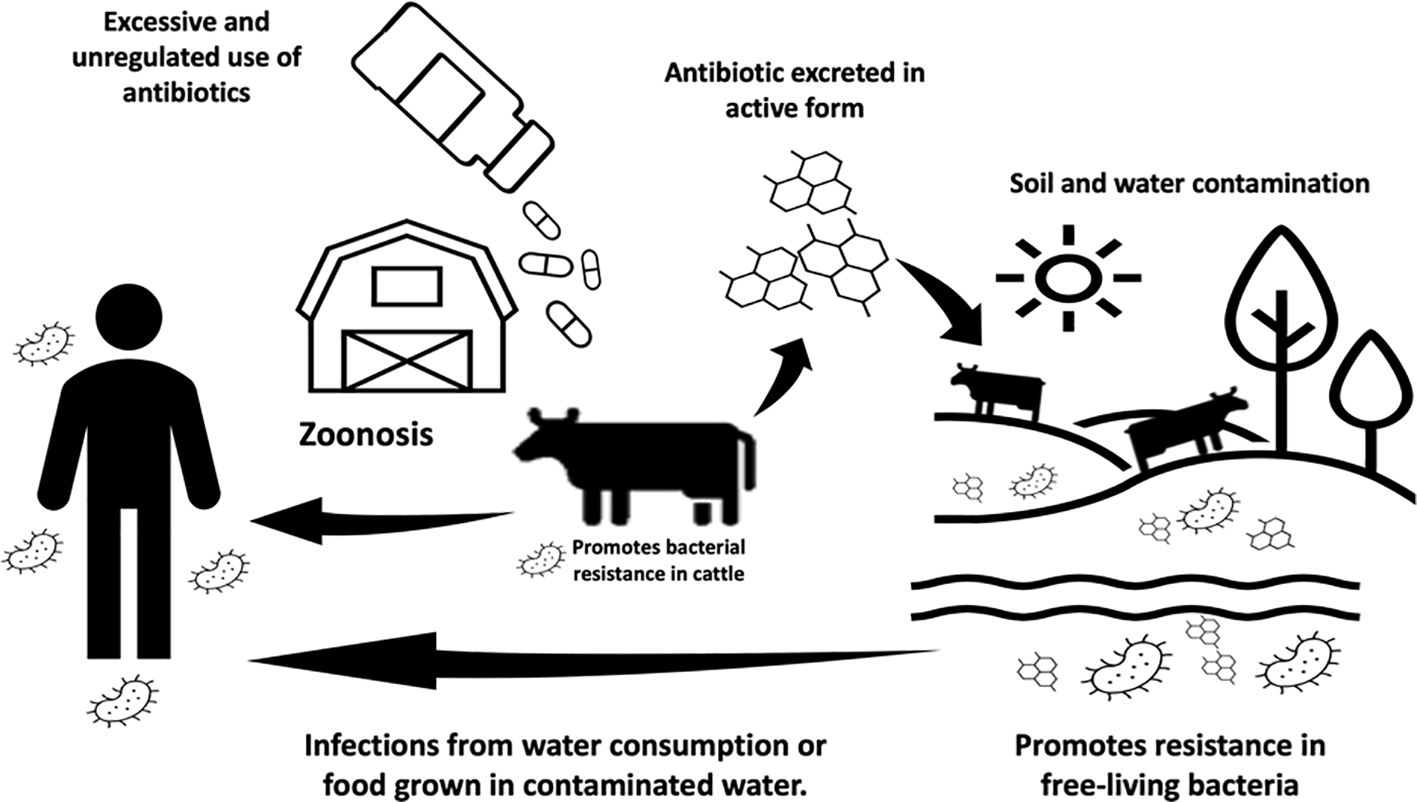

Conventional antibiotics have been extensively used for metaphylaxis and as growth promoters in various forms of livestock farming. The correlation between administering antibiotics at sub-therapeutic doses and enhanced animal weight gain is the driving force behind this practice (Dodds, 2017). These sub-therapeutic doses create a favorable environment for beneficial bacteria while impacting intestinal mucosa and motility, i.e., reducing undesirable pathogens and nutrient wastage (Bacanlı and Başaran, 2019) and improving overall animal health (Palma et al., 2020). However, the use and abuse of antibiotics exert selective pressure on microorganisms, contributing to the surges of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) within intensive animal food production systems. Metaphylaxis, in particular, extends this selective pressure to entire animal groups when an infection is identified in one individual (Economou and Gousia, 2015). In both cases, sensitive microorganisms in infected animals or asymptomatic carriers among healthy animals develop resistance (Figure 1) (Mellor et al., 2019).

Figure 1 Schematic pathway and ramifications of antibiotic contamination in animals and the environment.

The rise of AMR has direct and indirect consequences on our public health and global economy. The direct consequences of AMR include impacts on food security and animal health, with infected animals facing slaughter or mutilation in the absence of effective treatment. Indirect consequences include the associated costs of treating and quarantining infected animals and the public health risks of drug-resistant pathogens with zoonotic potential. The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed a unifying strategy known as One Health to prevent emerging zoonoses such as H1N1 flu and Hendra virus (Becker et al., 2022). The organization suggests shifting the current paradigm in our global food systems by recognizing the interdependence between the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, and the wider environment. This approach relies on the collective participation of communal, federal, and national entities to ensure the surveillance, regulation, and policy over antibiotic use (Figure 1) (Schmidt et al., 2017; Algammal et al., 2020; Bolte et al., 2020; Maity and Ambatipudi, 2021; Molineri et al., 2021; Velazquez-Meza et al., 2022). By working together, government and industries can identify emerging threats and develop more effective therapies.

Most organisms produce antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) as defense mechanisms in response to pathogenic infections. AMPs have gradually emerged as promising alternatives within the One Health approach in addressing the global challenge of AMR (Magana et al., 2020). First, the peptides exhibit broad-spectrum microbicidal activities against various pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses (Mookherjee et al., 2020). This makes them invaluable in both human and veterinary medicine. Second, AMPs do not induce bacterial resistance mechanisms due to their non- specific mechanisms of action on the bacterial membranes (Anaya-López et al., 2013; Assoni et al., 2020). This property is crucial in the fight against AMR, aligning with the One Health approach by offering a sustainable solution across human, animal, and environmental health. Finally, AMPs occur in Nature and are often biodegradable, posing fewer ecological risks than conventional antibiotics, which can persist and promote resistance development in microbial communities. By reducing environmental contamination, AMPs support the ecological aspect of the One Health approach. In summary, AMPs represent sustainable, broad-spectrum, and environmental- friendly alternatives to conventional antibiotics, directly supporting the goals of the One Health approach. Here, we describe the promising uses of antimicrobial peptides in veterinary medicine.

Environment and antibiotic bioaccumulation

Antibiotics, much like plastic and fossil fuels, are among the significant advancements of the 20th century that were developed and utilized for their immediate value without a comprehensive understanding of their long-term environmental and biological impacts. Consequently, the presence of antibiotics in various natural environments, including lakes, rivers, and fields fertilized with biosolids, is well-documented in current scientific literature (Storteboom et al., 2010; Booth et al., 2020). The persistence of antibiotics in the environment (Figure 1) is a concern because a substantial proportion of antibiotics is not entirely metabolized and is excreted while retaining their activity (Sukul et al., 2009). These residual antibiotics persist in natural settings, interacting with various bacteria. This includes organisms such as Escherichia coli, which can originate from wastewater discharges, and free-living bacteria like Vibrio cholerae (Jang et al., 2017; De, 2021). In these interactions, residual antibiotics can trigger various biological mechanisms that promote bacterial resistance. Among these mechanisms are selective pressure and the exchange of mobile genetic elements. Thus, the environment plays a crucial role in disseminating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) (Williams et al., 2016).

Zoonoses and the spread of antimicrobial resistance

Zoonoses are transmissible diseases from animals to humans, such as the well-documented examples of anthrax caused by Bacillus anthracis, bovine tuberculosis by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, brucellosis by Brucella abortus, and hemorrhagic colitis by Escherichia coli (Rahman et al., 2020). Beyond bacteria, zoonotic pathogens also include viruses (e.g., Hendra virus, influenza virus A) (Leifels et al., 2022) and parasites (e.g., Trypanosoma cruzi and Toxoplasma gondii) (Weiss, 2008). These pathogens can reach humans through direct contact with food, water, or the environment (Figure 1). They represent a global health threat due to our close relationships with animals in agriculture, as companions, and in the natural environment. Zoonoses disrupt our current food production systems, leading to the spread of foodborne outbreaks (Abebe et al., 2020; Preena et al., 2020). Zoonoses have also become the sources of AMR with pathogens like extended-spectrum beta- lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), becoming notably resistant to our antibiotics. Comprehensive reviews have documented the connections between zoonotic diseases and the spread of antimicrobial resistance (Srivastava and Purohit, 2020; Olaru et al., 2023). The indirect transmission of zoonoses involves vector insects or pets acting as a bridge between production areas and households (Bolte et al., 2020). The need to discover antibacterial molecules that are environmentally non-persistent has become a top priority. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) emerge as potential alternatives to contemporary antibiotics. To understand the progress in this domain, we listed peptides tested in livestock production (Table 1), considering associated bacteria for different livestock types and emphasizing achieved outcomes.

Swine livestock

In swine, one of the most important bacteria in veterinary clinics is Haemophilus parasuis, which causes Glässer’s disease. Teixeira and colleagues, in 2013, isolated a peptide from the culture supernatant of Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizezinii. Characterization of the peptide revealed antimicrobial activity against H. parasuis (Teixeira et al., 2013). On the other hand, using peptides as dietary additives for pigs has proven beneficial, as demonstrated by Tang and colleagues in 2011. They analyzed the effect of dietary supplementation with 100 mg/kg of lactoferricin peptide in a model of gastrointestinal infections by E. coli in 21-day-old pigs.

The study yielded positive results for the animals, with one of the main effects being the alteration of the gastrointestinal microbiome. This led to beneficial consequences such as improved nutrient retention and intestinal morphology, reduced incidences of gastrointestinal diseases like diarrhea, and promoted animal growth. This treatment reduced the concentration of E. coli and increased the presence of commensal bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. Additionally, it counteracted the effects of E. coli on intestinal architecture by promoting the height of intestinal villi in the jejunum and ileum compared to the group without the peptide. Furthermore, lower concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta, and IL-6 were found, along with higher concentrations of growth hormone in the treated pigs (Tang et al., 2011). Another group of peptides evaluated for swine pathogens were surfactins from B. subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis against intestinal pathogens Brachyspira hyodysenteriae and Clostridium perfringens, which cause swine dysentery and necrotic enteritis. In this group of peptides, both the dose-response relationship and treatment effectiveness were compared between them. The results showed that B. subtilis surfactin is more effective against B. hydrodysenteriae, while B. licheniformis surfactin is more effective against C. perfringens. This suggests that peptide isoforms between species may have selective effectiveness against specific pathogens (Horng et al., 2019).

Goat livestock

Among the peptides studied in goats, researchers have explored recombinant porcine defensin PBD-mI and the peptide isolated from flies, LUC-n. The supplementation of these peptides resulted in a notable alteration of the rumen microbiome, as demonstrated by the analysis of 16S bacterial genes and 18S rRNA genes of ciliated protozoa. Post-treatment analysis revealed an increase in beneficial genera, such as Fibrobacter, Anaerovibrio, Succiniclasticum, and Ophrysocolex, while pathogenic genera, like Selenomonas, Succinivibrio, Treponema, Polyplastron, Entodinium, and Isotricha decreased. Additionally, there were changes in enzymatic activity, including xylanase, pectinase, and lipase (Liu et al., 2017). These peptides underwent further evaluation using a different experimental design. Goats were divided into three groups: a control group, one supplemented with 2 grams per day of a combination of AMPs, and another with 3 grams per day. Ren and colleagues conducted this study in 2019 with a distinct experimental setup but arrived at results similar to the previous study: changes in digestion translated into an increase in the mass of treated animals compared to the control group. It is noteworthy that the group administered with 2 grams per day of the peptide combination showed greater mass gain than those given 3 grams, leading to the conclusion that the administered peptide quantity does not linearly affect the increase in body mass of animals, at least in goats. Therefore, an appropriate dosage is more relevant than a high amount administered (Ren et al., 2019). Bacteriocins from Bacillus thuringiensis were also evaluated in clinical isolates of goat mastitis. Various pathogenic species, such as Enterococcus durans, Brevibacillus spp., Enterobacter sp., Escherichia vulneris, Pantoea spp., Pseudomonas brenneri, and encapsulated yeast Cryptococcus neoformans, as well as several Staphylococcus species, were identified. The microbiocidal activity was observed in 67% of these isolated bacteriocins. However, species like Staphylococcus epidermidis, Enterobacter sp., E. vulneris, and C. neoformans proved resistant to all bacteriocins (Gutiérrez-Chávez et al., 2016). Finally, a novel perspective on mastitis treatment in goats involves the generation of peptides directly in milk. This is achieved by transfecting animals with plasmid vectors containing the peptide sequence. For instances, cecropin B, an AMP from the giant silk moth, was transfected into goat mammary glands, resulting in inhibitory effects against S. aureus (Luo et al., 2013).

Bovine livestock

Cattle suffer from various zoonotic diseases, including tuberculosis (e.g., Mycobacterium bovina) and mastitis (e.g., Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Staphylococcus aureus), leading severe loss in animal production. Several peptides have been particularly evaluated to treat S. aureus-induced bovine mastitis and ulcers on teats, as the pathogen can reside intracellularly within mammary gland epithelial cells (Alva-Murillo et al., 2017). For example, the peptides NZ2114 and MP1102, derived from plectasin, an amphipathic peptide isolated from the fungus Pseudoplectania nigrella, were evaluated in murine models of S. aureus-induced mastitis and sterile milk cultures. Of note, milk components (among other pathophysiological factors) might significantly affect peptides (Schmelcher et al., 2015). As a result, the peptides were also tested on bovine mammary epithelial cells infected with this bacterium. Both peptides exhibited activity against S. aureus in sterile milk cultures, indicating that their effectiveness is not compromised in milk. They demonstrated intracellular activity against S. aureus without any cytotoxic effects at concentrations of up to 100 μg/mL. These peptides were also effective in experimental mastitis treatment (Li et al., 2017). Bacteriocins are another group of antimicrobial peptides that were evaluated against S. aureus-induced bovine mastitis. As such example, in 2009, Barbosa and colleagues determined that S. aureus AMR isolates obtained from milk of cows diagnosed with mastitis were sensitive to five bacteriocins from B. thuringiensis, with morricin 269 and kurstacin 287 exhibiting the greatest activity (Barboza-Corona et al., 2009). Likewise, bovicin HC5, a bacteriocin obtained from Streptococcus equinus HC5 (found in the horse gastrointestinal tract), possesses valuable characteristics for food preservation. It is a thermo-stable peptide with a mechanism of action described as lipid II-dependent, soluble at neutral pH, and effective even in acidic pH. This peptide inhibited the growth of mastitis-causing bacteria such as S. aureus, S. agalactiae, Streptococcus bovis, and Streptococcus uberis at concentrations ranging from 40 to 2560 arbitrary units (u.a.)/mL (Godoy-Santos et al., 2019). Finally, in 2021, Sharma and colleagues proposed the directed expression of the tracheal antimicrobial peptide (Tap) to treat S. aureus-associated mastitis in mice. They observed significant antibacterial effects in both in vitro and in vivo experiments by introducing a vector with the TAP peptide into mice infected with S. aureus associated with bovines (Sharma et al., 2021). Similarly, in 2017, the expression of a peptide derived from lactoferricin was carried out using the PiggyBac plasmid in bovine mammary epithelial cells, resulting in successful protection against S. aureus and E. coli (Sharma et al., 2017). The aforementioned peptides are all derived from external sources. Some peptides originally from cattle or their milk have also been studied for their antimicrobial properties. In 2007, Chockalingam and co-workers synthesized the hybrid peptide named bBPI90–99,148-161, where bBPI stands for bovine bactericidal permeability-increasing protein. This hybrid peptide had an average inhibitory concentration of 16 μg/mL against E. coli and 128 μg/mL for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, but was ineffective against Serratia marcescens. In addition, the antimicrobial activity of the peptide decreased after being suspended in milk, while it remained stable when tested in serum. These results indicated the importance of assessing different fluids in which the peptides may be administered (Chockalingam et al., 2007). Cow milk also holds a rich source of proteins and potential AMPs. Examples include beta- lactoglobulin, alpha-lactalbumin, and lactoferrin (Mohanty et al., 2016). The latter is a glycoprotein with iron- binding properties that plays a significant role in the bovine immune system. This 692- residue protein has demonstrated antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects (Woodman et al., 2018). Lactoferricin is a small peptide derived from lactoferrin, which has been effective in treating subclinical mastitis caused by E. coli and Staphylococci in cattle. It also exhibited in vitro activity against an alga called Prototheca zopfii, responsible for protothecal mastitis, and yeast strains causing fungal mastitis (Bruni et al., 2016).

Poultry industry

Clostridium perfringens is one of the most significant pathogens in the poultry industry, being the primary etiological agent of necrotic enteritis, a disease that causes substantial economic losses for producers (Ben Lagha et al., 2017). Factors predisposing to infection and various strategies to control the effects of this pathogen have been extensively studied (Allaart et al., 2013). In 2015, Wang and colleagues reported sublancin, a bacteriocin produced by B. subtilis, for its potential antimicrobial effect against C. perfringens in chickens. Their results revealed that the peptide displayed similar antimicrobial activity to the commercial antibiotic lincomycin. Unlike the group administered with sublancin, the lincomycin-treated group also experienced a reduction in Lactobacillus colonies, a commensal bacterium in the chicken digestive system. Sublancin might not affect other bacterial species in the avian intestinal microbiomes, but there is evidence of potentially greater specificity between species compared to conventional antibiotic treatments (Wang et al., 2015). Alternatively, peptides have also been employed as dietary supplements to promote growth in poultry. One such example is piscidin, isolated from the fish Epinephelus lanceolatus, which was utilized as a dietary additive and compared with control groups. Its antimicrobial activity against strains of S. aureus, E.coli, P. aeruginosa, and various strains of Riemerella antipestifer was evaluated, with the first three and some R. antipestifer strains proving sensitive to the peptide (Tai et al., 2020). Piscidin also exhibited immunomodulatory properties, increasing the secretion of interferon-gamma, immunoglobulins G, and interleukin-10 compared to the control group. Finally, the peptide induced significant changes in bacterial communities, increasing the families Enterococcaceae and Lactobacilliaceae while decreasing Enterobacteriaceae and Staphylococceaceae.

Antimicrobial peptides in livestock-relevant clinical strains

Antimicrobial peptides have been used against important clinical strains of the same genus and species. For example, bacteriocins isolated from S. aureus and S. epidermidis against other strains of S. aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from bovine mastitis. In 2007, Varella Coelho and co-workers identified bacteriocin A53 had a moderate effect against some clinical strains. However, when used in combination with A70, a bacteriocin with a similar effect alone, the synergistic effect resulted in increasing the inhibition percentages in S. agalactiae (i.e., from 67.6% to 91.9%) and in S. aureus (i.e., from 74.4% to 91.5%) (Varella Coelho et al., 2007). These results suggest that antimicrobial peptides from pathogenic bacteria might be helpful against similar pathogens. Another bacteriocin named nisin from Lactococcus lactis has been noted for having high antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria. In 2019, Castelani and co-workers evaluated its antimicrobial potential against Staphylococcus spp. isolated from cases of bovine mastitis. The peptide exhibited antibacterial effects against antibiotic-resistant strains. In combination with dioctadecyldimethylammonium bromide, a quaternary amine with broad antimicrobial activity, it enhanced the susceptibility of isolates to the bacteriocin, reducing the minimum bactericidal concentration from 50 to 3 µg/mL (Castelani et al., 2019). These two examples showed that synergistic effects should be considered in future studies.

Conclusions

The significance of developing therapies in veterinary medicine aligns with the “One Health” concept, acknowledging the interdependence of health across ecosystems, including livestock, pets, wildlife, and plants. Embracing this holistic approach, the urgency to invest in novel peptide-based antimicrobials becomes apparent. These peptides exhibit dual mechanisms of action: direct effects on microorganisms and stimulation of the host’s immune response, enhancing their effectiveness against infections. A particularly challenging scenario is observed in bovine mastitis, where the need for peptides capable of remaining stable in the presence of milk components is crucial. Regulatory challenges and concerns about resistance to AMPs complicate their applications in livestock. Despite these challenges, the slower pace of bacterial adaptation to these peptides compared to conventional antibiotics places AMPs as novel therapeutic agents against infections, extending beyond the realms of veterinary clinics and mastitis. AMPs offer a potential solution to the scarcity of effective antibiotics against multidrug-resistant bacteria, emphasizing the need for responsible antibiotic use across all sectors. Efforts to manage antibiotic use, including exploring strategies like genetically engineered microbes for environmental clean-up, are imperative for global health and food security.

Author contributions

OR: Investigation, Writing – original draft. GO: Writing – review & editing. FP: Validation, Writing – review & editing. CB-S: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Dirección General de Investigaciones (DGI-UV), Universidad Veracruzana. 2023 Call for Support for Publication Payments.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Dirección General de Cómputo y de Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación (DGTIC) of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) for allocation of computer time on the Miztli supercomputer and DGAPA-UNAM grant PAPIIT- IN210023. And to Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (CYTED) (219RT0573). Red Temática en Salud. Desarrollo de Péptidos Antivirales y Antimicrobianos para Cepas Multi-resistentes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abebe, E., Gugsa, G., Ahmed, M. (2020). Review on major food-borne zoonotic bacterial pathogens. J. Trop. Med 2020, e4674235. doi: 10.1155/2020/4674235

Algammal, A. M., Hetta, H. F., Elkelish, A., Alkhalifah, D. H. H., Hozzein, W. N., Batiha, G. E.-S., et al. (2020). Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): One health perspective approach to the bacterium epidemiology, virulence factors, antibiotic- resistance, and zoonotic impact. Infect. Drug Resist 13, 3255–3265. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S272733

Allaart, J. G., van Asten, A. J. A. M., Gröne, A. (2013). Predisposing factors and prevention of Clostridium perfringens-associated enteritis. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis 36, 449–464. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2013.05.001

Alva-Murillo, N., Ochoa-Zarzosa, A., López-Meza, J. E. (2017). Sodium Octanoate Modulates the Innate Immune Response of Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells through the TLR2/P38/JNK/ERK1/2 Pathway: Implications during Staphylococcus aureus Internalization. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol 7. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00078

Anaya-López, J. L., López-Meza, J. E., Ochoa-Zarzosa, A. (2013). Bacterial resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. Crit. Rev. Microbiol 39, 180–195. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.699025

Assoni, L., Milani, B., Carvalho, M. R., Nepomuceno, L. N., Waz, N. T., Guerra, M. E. S., et al. (2020). Resistance mechanisms to antimicrobial peptides in gram- positive bacteria. Front. Microbiol 11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.593215

Bacanlı, M., Başaran, N. (2019). Importance of antibiotic residues in animal food. Food Chem. Toxicol 125, 462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.01.033

Barboza-Corona, J. E., de la Fuente-Salcido, N., Alva-Murillo, N., Ochoa-Zarzosa, A., López-Meza, J. E. (2009). Activity of bacteriocins synthesized by Bacillus thuringiensis against Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated to bovine mastitis. Vet. Microbiol 138, 179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.03.018

Becker, D. J., Eby, P., Madden, W., Peel, A. J., Plowright, R. K. (2022). Ecological conditions predict the intensity of Hendra virus excretion over space and time from bat reservoir hosts. Ecol. Letter 26, 23–36. doi: 10.1111/ele.14007

Ben Lagha, A., Haas, B., Gottschalk, M., Grenier, D. (2017). Antimicrobial potential of bacteriocins in poultry and swine production. Vet. Res 48, 22. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0425-6

Bolte, J., Zhang, Y., Wente, N., Mahmmod, Y. S., Svennesen, L., Krömker, V. (2020). Comparison of phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance patterns associated with Staphylococcus aureus mastitis in German and Danish dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci 103, 3554–3564. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-17765

Booth, A., Aga, D. S., Wester, A. L. (2020). Retrospective analysis of the global antibiotic residues that exceed the predicted no effect concentration for antimicrobial resistance in various environmental matrices. Environ. Int 141, 105796. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105796

Bruni, N., Capucchio, M. T., Biasibetti, E., Pessione, E., Cirrincione, S., Giraudo, L., et al. (2016). Antimicrobial activity of lactoferrin-related peptides and applications in human and veterinary medicine. Molecules 21, 752. doi: 10.3390/molecules21060752

Castelani, L., Arcaro, J. R. P., Braga, J. E. P., Bosso, A. S., Moura, Q., Esposito, F., et al. (2019). Short communication: Activity of nisin, lipid bilayer fragments and cationic nisin-lipid nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus spp. isolated bovine mastitis. J. Dairy Sci 102, 678–683. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-15171

Chockalingam, A., Zarlenga, D. S., Bannerman, D. D. (2007). Antimicrobial activity of bovine bactericidal permeability–increasing protein–derived peptides against gram-negative bacteria isolated from the milk of cows with clinical mastitis. Am. J. Vet. Res 68, 1151–1159. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.68.11.1151

De, R. (2021). Mobile genetic elements of vibrio cholerae and the evolution of its antimicrobial resistance. Front. Trop. Dis 2. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2021.691604

Dodds, D. R. (2017). Antibiotic resistance: A current epilogue. Biochem. Pharmacol 134, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.12.005

Economou, V., Gousia, P. (2015). Agriculture and food animals as a source of antimicrobial- resistant bacteria. Infect. Drug Resist 8, 49–61. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S55778

Godoy-Santos, F., MS, P., Barbosa, A. A. T., Brito, M. A. V. P., Mantovani, H. C. (2019). Efficacy of a ruminal bacteriocin against pure and mixed cultures of bovine mastitis pathogens. Indian J. Microbiol 59, 304–312. doi: 10.1007/s12088-019-00799-w

Gutiérrez-Chávez, A. J., Martínez-Ortega, E. A., Valencia-Posadas, M., León-Galván, M. F., de la Fuente-Salcido, N. M., Bideshi, D. K., et al. (2016). Potential use of Bacillus thuringiensis bacteriocins to control antibiotic-resistant bacteria associated with mastitis in dairy goats. Folia Microbiol 61, 11–19. doi: 10.1007/s12223-015-0404-0

Horng, Y.-B., Yu, Y.-H., Dybus, A., Hsiao, F. S.-H., Cheng, Y.-H. (2019). Antibacterial activity of Bacillus species-derived surfactin on Brachyspira hyodysenteriae and Clostridium perfringens. AMB Express 9, 188. doi: 10.1186/s13568-019-0914-2

Jang, J., Hur H, -G., Sadowsky, M. J., Byappanahalli, M. N., Yan, T., Ishii, S. (2017). Environmental Escherichia coli: ecology and public health implications—a review. J. Appl. Microbiol 123, 570–581. doi: 10.1111/jam.2017.123.issue-3

Leifels, M., Khalilur Rahman, O., Sam, I.-C., Cheng, D., Chua, F. J. D., Nainani, D., et al. (2022). The one health perspective to improve environmental surveillance of zoonotic viruses: lessons from COVID-19 and outlook beyond. ISME Commun 2, 107. doi: 10.1038/s43705-022-00191-8

Li, L., Wang, L., Gao, Y., Wang, J., Zhao, X. (2017). Effective Antimicrobial Activity of Plectasin-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides against Staphylococcus aureus Infection in Mammary Glands. Front. Microbiol 8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02386

Liu, Q., Yao, S., Chen, Y., Gao, S., Yang, Y., Deng, J., et al. (2017). Use of antimicrobial peptides as a feed additive for juvenile goats. Sci. Rep 7, 12254. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12394-4

Luo, C., Yin, D., Gao, X., Li, Q., Zhang, L. (2013). Goat mammary gland expression of cecropin B to inhibit bacterial pathogens causing mastitis. Anim. Biotechnol 24, 66–78. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2012.745417

Magana, M., Pushpanathan, M., Santos, A. L., Leanse, L., Fernandez, M., Ioannidis, A., et al. (2020). The value of antimicrobial peptides in the age of resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis 20, e216–e230. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30327-3

Maity, S., Ambatipudi, K. (2021). Response to Comments on “Mammary microbial dysbiosis leads to the zoonosis of bovine mastitis: a One-Health perspective” by Maity and Ambatipudi. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol 97(1), fiaa241. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiab079

Mellor, K. C., Petrovska, L., Thomson, N. R., Harris, K., Reid, S. W. J., Mather, A. E. (2019). Antimicrobial resistance diversity suggestive of distinct salmonella typhimurium sources or selective pressures in food-production animals. Front. Microbiol 10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00708

Mohanty, D., Jena, R., Choudhury, P. K., Pattnaik, R., Mohapatra, S., Saini, M. R. (2016). Milk derived antimicrobial bioactive peptides: A review. Int. J. Food Prop 19, 837–846. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2015.1048356

Molineri, A. I., Camussone, C., Zbrun, M. V., Suárez Archilla, G., Cristiani, M., Neder, V., et al. (2021). Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Vet. Med 188, 105261. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2021.105261

Mookherjee, N., Anderson, M. A., Haagsman, H. P., Davidson, D. J. (2020). Antimicrobial host defence peptides: functions and clinical potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 19, 311–332. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0058-8

Olaru, I. D., Walther, B., Schaumburg, F. (2023). Zoonotic sources and the spread of antimicrobial resistance from the perspective of low and middle-income countries. Infect. Dis. Poverty 12, 59. doi: 10.1186/s40249-023-01113-z

Palma, E., Tilocca, B., Roncada, P. (2020). Antimicrobial resistance in veterinary medicine: An overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci 21, 1914. doi: 10.3390/ijms21061914

Preena, P. G., Swaminathan, T. R., Kumar, V. J. R., Singh, I. S. B. (2020). Antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture: a crisis for concern. Biologia 75, 1497–1517. doi: 10.2478/s11756-020-00456-4

Rahman, M. T., Sobur, M. A., Islam, M. S., Ievy, S., Hossain, M. J., El Zowalaty, M. E., et al. (2020). Zoonotic diseases: Etiology, impact, and control. Microorganisms 8, 1405. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091405

Ren, Z., Yao, R., Liu, Q., Deng, Y., Shen, L., Deng, H., et al. (2019). Effects of antibacterial peptides on rumen fermentation function and rumen microorganisms in goats. PLoS One 14, e0221815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221815

Schmelcher, M., Powell, A. M., Camp, M. J., Pohl, C. S., Donovan, D. M. (2015). Synergistic streptococcal phage λSA2 and B30 endolysins kill streptococci in cow milk and in a mouse model of mastitis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 99, 8475–8486. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6579-0

Schmidt, K., Mwaigwisya, S., Crossman, L. C., Doumith, M., Munroe, D., Pires, C., et al. (2017). Identification of bacterial pathogens and antimicrobial resistance directly from clinical urines by nanopore-based metagenomic sequencing. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 72, 104–114. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw397

Sharma, A., Gaur, A., Kumar, V., Sharma, N., Patil, S. A., Verma, R. K., et al. (2021). Antimicrobial activity of synthetic antimicrobial peptides loaded in poly-Ɛ-caprolactone nanoparticles against mycobacteria and their functional synergy with rifampicin. Int. J. Pharm 608, 121097. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121097

Sharma, N., Huynh, D. L., Kim, S. W., Ghosh, M., Sodhi, S. S., Singh, A. K., et al. (2017). A PiggyBac mediated approach for lactoferricin gene transfer in bovine mammary epithelial stem cells for management of bovine mastitis. Oncotarget 8, 104272–104285. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.v8i61

Srivastava, S., Purohit, H. J. (2020). Zoonosis: an emerging link to antibiotic resistance under “One health approach. ” Indian J. Microbiol 60, 139–152. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00860-z

Storteboom, H., Arabi, M., Davis, J. G., Crimi, B., Pruden, A. (2010). Identification of antibiotic- resistance-gene molecular signatures suitable as tracers of pristine river, urban, and agricultural sources. Environ. Sci. Technol 44, 1947–1953. doi: 10.1021/es902893f

Sukul, P., Lamshöft, M., Kusari, S., Zühlke, S., Spiteller, M. (2009). Metabolism and excretion kinetics of 14C-labeled and non-labeled difloxacin in pigs after oral administration, and antimicrobial activity of manure containing difloxacin and its metabolites. Environ. Res 109, 225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.12.007

Tai, H.-M., Huang, H.-N., Tsai, T.-Y., You, M.-F., Wu, H.-Y., Rajanbabu, V., et al. (2020). Dietary supplementation of recombinant antimicrobial peptide Epinephelus lanceolatus piscidin improves growth performance and immune response in Gallus gallus domesticus. PLoS One 15, e0230021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230021

Tang, Z. R., ZH, S., XS, T., ZM, F., Zhou, D., DF, X., et al. (2011). Dietary bovine lactoferricin improved gut microflora, benefited intestinal mucosal morphology and inhibited circular cytokines delivery in 21-day weaned piglets. J. Appl. Anim. Res 39, 153–157. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2011.565570

Teixeira, M. L., Rosa, A. D., Brandelli, A. (2013). Characterization of an antimicrobial peptide produced by Bacillus subtilis subsp. spizezinii showing inhibitory activity towards Haemophilus parasuis. Microbiol 159, 980–988. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.062828-0

Varella Coelho, M. L., Do Santos Nascimento, J., Fagundes, P. C., Madureira, D. J., de Oliveira, S. S., Vasconcelos de Paiva Brito, M. A., et al. (2007). Activity of staphylococcal bacteriocins against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae involved in bovine mastitis. Res. Microbiol 158, 625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.07.002

Velazquez-Meza, M. E., Galarde-López, M., Carrillo-Quiróz, B., Alpuche-Aranda, C. M. (2022). Antimicrobial resistance: One Health approach. Vet. World 15, 743–749. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2022.743-749

Wang, S., Zeng, X. F., Wang, Q. W., Zhu, J. L., Peng, Q., Hou, C. L., et al. (2015). The antimicrobial peptide sublancin ameliorates necrotic enteritis induced by Clostridium perfringens in broilers. J. Anim. Sci 93, 4750–4760. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-9284

Weiss, L. M. (2008). Zoonotic parasitic diseases: Emerging issues and problems. Int. J. Parasitol 38, 1209–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.05.005

Williams, M. R., Stedtfeld, R. D., Guo, X., Hashsham, S. A. (2016). Antimicrobial resistance in the environment. Water Environ. Res 88, 1951–1967. doi: 10.2175/106143016X14696400495974

Keywords: antimicrobial peptides, veterinary medicine, mastitis, One Health, bacterial resistance

Citation: Robles Ramirez O, Osuna G, Plisson F and Barrientos-Salcedo C (2024) Antimicrobial peptides in livestock: a review with a one health approach. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14:1339285. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1339285

Received: 15 November 2023; Accepted: 25 March 2024;

Published: 24 April 2024.

Edited by:

Sandra Aguiar, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Sandip Patil, Shenzhen Children’s Hospital, ChinaMagdalena Zalewska, University of Warsaw, Poland

Copyright © 2024 Robles Ramirez, Osuna, Plisson and Barrientos-Salcedo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carolina Barrientos-Salcedo, Y2FiYXJyaWVudG9zQHV2Lm14

Oscar Robles Ramirez

Oscar Robles Ramirez Gabriel Osuna

Gabriel Osuna Fabien Plisson

Fabien Plisson Carolina Barrientos-Salcedo

Carolina Barrientos-Salcedo