Citizens' Contrasting Aspirations About Their Political System: Entrustment, Participation, Identification and Control

- Centre Emile Durkheim, Sciences po Bordeaux, Pessac, France

Empirical political science has increasingly focused on citizens' conceptions of their political system. Most existing studies draw upon large quantitative datasets which have produced contradictory results. Qualitative approaches are used more and more commonly to identify the general narrative produced by ordinary citizens on their political system, but they tend to underplay the variations found in their discourses. In this article, I use semi-directed interviews to explore citizens' contrasting aspirations about their political system. This article is based on 32 interviews conducted with French citizens across Fall and Winter 2017 and on 24 interviews conducted during the Yellow Vests movement in fall 2019. During these interviews, citizens were asked to define in their own terms what politics is, what it should achieve, what the flaws and advantages of their political system are and what should be changed. These citizens have produced four ideal-typical discourses, uncovering four distinct conceptions of what the political system is, how it legitimizes itself, what types of procedures it should lay on and what types of outcomes it should produce. Citizens' discourses heavily focus on alternative logics of political representation, which remains unavoidable to channel political decisions. They express four competing aspirations: entrustment, participation, identification, and control & sanction. The two latter conceptions remain under-explored empirically.

The conceptions of the political system of citizens who live in democracy is a topic that has attracted more and more concern in recent years. Quantitative research has underlined the existence of competing aspirations. Support for traditional representative democracy is challenged by a growing demand for citizen participation (Norris, 1999, 2011) and the prevalence of “stealth” democratic attitudes supporting the empowerment of experts and successful businessmen (Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009; Coffé and Michels, 2014; Fernández-Martínez and Fábregas, 2018). Qualitative approaches have adopted another perspective which focuses on the general narrative produced by ordinary citizens on their political system (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2002; Clarke et al., 2018; Saunders and Klandermans, 2019).

How can we account for the contrasting aspirations expressed by citizens about their political system using qualitative methods? I argue that it is necessary to complement existing studies with qualitative analyses tackling specifically the variation found in the ideal-typical discourses produced by citizens on their political system. To do so, this article is based on individual interviews with French citizens, complemented with the use of interviews with Yellow Vests activists' conducted between 2017 and 2019. France is an interesting laboratory to explore this research question for several reasons. Firstly, France is a semi-presidential majoritarian democracy in which alternatives to representative democracy are limited, parties are particularly weak, where the presidential figure is dominant, and where a large part of voters are not represented in Parliament (Grossman and Sauger, 2010). Secondly, it is characterized by an intensive use of democratic reforms (Bedock, 2017), by the existence of important social movements challenging the current state of French democracy, and by a very low level of confidence in existing political institutions (Grossman and Sauger, 2017). Debates about the “right” political system are therefore unusually high on the agenda compared to other democracies. This enables an easier access to citizens' views on the political system during interviews.

By using an inductive and qualitative approach, I show that French citizens produce four ideal-typical discourses about their political system that reveal four distinct conceptions of what the political system is, how it legitimizes itself, what types of procedures it should lay on and what types of outcomes it should produce. My focus was on the political system in general. Easton defined it as the interactions through which values are authoritatively allocated in a society (Easton, 1965). We could also describe it as the decision-making process turning inputs into policy outputs. Even though we adopted this wide focus over the course of the inquiry, we found that citizens' discourses about the political system are mostly structured by alternative conceptions of political representation.

The first section comes back on the quantitative and qualitative empirical studies on citizens' aspirations about their political system, and on their limitations. The second section briefly presents the material and the thematic analysis. Sections The Aspiration to Entrustment, The Aspiration to Participation, The Aspiration to Identification, and The Aspiration to Control and Sanction discuss in turn the four aspirations emerging from our thematic analysis: entrustment, participation, identification, and control. For each of these conceptions, I analyze the definition of politics, the discourses about elected representatives, about the political process and about policy outputs identified in the discourses of the interviewees, before discussing the social and political properties of the individuals who held the most archetypical discourses.

What Do Citizens Expect From Their Political System? Existing Empirical Evidence

Participation, Expertise, and Representation: Three Competing Aspirations Identified by Survey Research

In recent decades, many scholars have conducted surveys on citizens' preferences regarding how democracy should be organized (to name a few, see Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009; Webb, 2013; Coffé and Michels, 2014; Font et al., 2015; Caluwaerts et al., 2018). They show the co-existence of three models of democracy (Bengtsson and Christensen, 2016). The first model—the participation model—implies that citizens should be actively involved in decision-making through extensive mechanisms of participation. The expertise/technocratic model insists on efficiency, values experts to take political decisions, and requires limited citizens' involvement. Finally, the representation/elitist model posits that elected representatives should remain in charge of political decisions and be accountable in front of their voters.

A growing share of the population supports the idea to give more opportunities to citizens to get involved in the political process, or even to make them the main policy-makers (Webb, 2013; Font et al., 2015; Bengtsson and Christensen, 2016; del Río et al., 2016; Gherghina and Geissel, 2017). Some studies focus on more specific instruments of participation, such as referendums (Bowler et al., 2007; Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009; Schuck and de Vreese, 2015; Bowler and Donovan, 2019), deliberative democracy (Neblo et al., 2010; Caluwaerts et al., 2018), or sortition to involve citizens or even replace politicians in the decision-making process (Bedock and Pilet, 2020). These studies all show that a significant proportion of individuals across various contexts support increased citizen participation in various forms, direct democracy being particularly popular. Other scholars insist on the pervasiveness of stealth democratic attitudes among ordinary citizens. Stealth democrats want independent experts or successful businessmen to take the most important decisions and reject partisan politics. The prevalence of stealth democratic attitudes has been observed in various contexts: the US (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2002; VanderMolen, 2017; Medvic, 2019), Finland (Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009), the Netherlands (Coffé and Michels, 2014), or the UK (Webb, 2013; Stoker and Hay, 2017).

In other words, a large proportion of citizens across different countries seem not to consider that elections and representation are the only acceptable mechanism to take political decisions in democracy. These contrasting aspirations (participation, expertise, representation) are not randomly distributed. Several authors show that reforms reinforcing the role of citizens in the political process are supported by young, educated, politically interested and post-materialist individuals (Donovan and Karp, 2006; Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009; Norris, 2011; Dalton and Welzel, 2014; Schuck and de Vreese, 2015; Dalton, 2017). Other authors demonstrate that support for alternatives such as the empowerment of experts, lay citizens, or direct democracy is linked with a strong disenchantment with representative democracy (Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009; Neblo et al., 2010; Webb, 2013; Schuck and de Vreese, 2015; del Río et al., 2016; Bertsou and Pastorella, 2017; Gherghina and Geissel, 2018). Political orientation also matters: left-wing oriented individuals are more supportive of participatory mechanisms, whereas right-wing individuals are more prone to support technocratic mechanisms (Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009; Bertsou and Pastorella, 2017). Finally, recent studies have shown that individuals who are more politically and socially marginalized are more likely to support various alternatives to the political status quo (Ceka and Magalhães, 2020), such as the increased use of referendums (Bowler and Donovan, 2019) or sortition (Vandamme et al., 2018; Bedock and Pilet, 2020).

Despite these general trends, existing results are often contradictory and implicitly assume that citizens who express support for alternative actors in surveys favor mechanisms that would strongly disrupt political representation. These pieces of work identify variations in the conceptions of the political system among ordinary citizens, but these variations are very dependent upon the indicators that are being used. Responses to survey questions about process preferences depend, to a significant extent, on the questions being asked. According to Clarke et al. (2018, 179), “if researchers ask questions designed to confirm stealth theories, they tend to achieve such confirmation; but if they ask questions designed to confirm alternative “sunshine” theories, they also tend to achieve such confirmation.” Citizens have a harder time taking a clear position when they are presented with unfamiliar options and often express at once support for apparently contradictory options (Bengtsson, 2012). This calls for methodological approaches giving citizens “the opportunity to speak or write freely about formal politics without being guided by tightly worded survey instruments” (Clarke et al., 2018, 179).

Stealth Democracy, Stealth Populism or Participatory Skepticism? Qualitative Evidence

Another strand of research has used qualitative methods (in particular archives and focus groups) to identify how citizens speak about the political system in their own words. These studies have tempered the idea that citizens have become more assertive and more willing to participate outside of electoral politics (Norris, 1999, 2011; Dalton and Welzel, 2014).

Using focus groups conducted in the US in the early 2000s, Hibbing and Theiss-Morse have developed an influential study on “stealth democracy” (see supra.). They argue that surveys suggesting that people want to increase the power of ordinary citizens are misleading and only measure the intense distrust of American citizens of their political elites. During the focus groups, politicians were considered as knowledgeable but self-interested and blinded by partisan considerations, whereas citizens were considered as too politically apathetic to become more involved in politics. Interviewees defined governing as good management rather than the representation of diverse interests. As a consequence, citizens expressed the will to be governed by independent experts or successful businessmen that would move decision-making away from clashing interests and be instinctively in touch with citizens' aspirations.

In a more recent study conducted in the United-Kingdom, Clarke et al. used archives comprising hundreds of letters from panelists about politicians, parties, and government, and compared the post-World War II period with the 2000–2015 period. They show the increasing prevalence of “anti-politics,” i.e., “citizens' negative sentiment toward the activities and institutions of formal politics (politicians, parties, elections, councils, parliaments, governments” (Clarke et al., 2018, 2–3). They argue that already after the Second World War, British citizens' expressed a “stealth” understanding of democracy and saw parties as diversions from the general interest. Contrary to what Hibbing and Theiss-Morse suggested, British citizens do not want experts to be in charge, but statesmen who would work in grand coalitions. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, “a stealth understanding of politics has transformed into a stealth populist understanding, by which many citizens imagine “the people”—who largely agree and so just need action from competent, independent representatives—but also an incompetent and out of touch political elite” (Clarke et al., 2018, 262). The authors argue that what is expected from a “good politician” has changed over time: “many citizens came to expect politicians not only for the people (sincere, hard-working, able, moderate, strong), but also of the people (normal, in touch)”. Other studies using focus groups show the importance of the national context–party configurations, current political institutions, recent social movements and more generally of current social and political events–to understand the differences in the way in which citizens see politics and their political systems (Saunders and Klandermans, 2019), but confirm the prevalence of “anti-politics” feelings.

These examples show the importance of not relying solely on survey research to analyze citizens' aspirations about their political system and invite political scientists to question their own understanding of democracy. Indeed, even more so since the “deliberative turn” taken by political theory (Goodin, 2008), political scientists tend to value deliberation as the best way to restore faith in politics, often assuming that most, if not all citizens, also share this view. All of these studies have one strong limitation: they focus on the single dominant narrative found in the countries investigated and not on the variations found in the ideal-typical discourses of citizens. Research conducted in Spain have started to challenge this dominant approach, focusing on the alternative forms of decision-making privileged by different groups of citizens. Although citizens do share a relatively similar understanding of the failures of their political system—blaming political parties and the professionalization of politics–not all groups favor the same alternatives (Ganuza and Font, 2018). Disadvantaged social groups are unconvinced about their own ability to get involved in the political process and skeptical of participatory democracy (García-Espín and Ganuza, 2017). By contrast, people who are engaged politically and vote for leftist parties tend to consider that the solution to the failures of the Spanish political system is more participation. Even if exploratory in nature, this article aims at showing that there may be a way to reconcile quantitative and qualitative approaches by considering at once the variety of conceptions and the social and political differences that could explain it–as done by survey research–and by analyzing a rich material enabling to dig deeper in people's discourses—as done by qualitative research.

Interview Collection and Thematic Analysis

This article relies on individual interviews. Focus groups are more heuristic when one focuses on the shared understanding that interviewees have on a given topic in homogenous groups (Van Ingelgom, 2014), and on how interactions and disagreements enable to make these shared meanings emerge (Duchesne and Haegel, 2004). By contrast, I am interested in the differences and the variations found in the discourses of citizens about their political system, but also in the way in which these can be related with their socialization.

The following conclusions are mainly based on in depth qualitative interviews with 32 French citizens conducted in Fall 2017 about their visions of the political system, with individuals of various social backgrounds, generations, levels of diploma, places of residence, ideological preferences and political engagement. The main objective behind the selection of interviewees was to uncover the variety of discourses formulated about the French political system by diversifying as much as possible the profile of the interviewees (see Supplementary Appendix 1). To better understand one of the four aspirations that these interviews enabled to identify (see infra.), I also used elements of the 24 interviews conducted with activists during the Yellow Vests Movement with other colleagues (Bedock et al., 2020) in Spring 2019 as a complementary empirical material. This social movement has gathered a majority of individuals coming from disadvantaged social backgrounds as well as many people who mobilized for the very first time (Collectif d'enquête sur les Gilets jaunes, 2019).

Our two samples are not fully representative of the French population. For the 32 interviews with lay citizens, there is a gender imbalance in favor of men, individuals between 18 and 24 years old and people over 65 years old, people with a university degree and executives and professionals. This imbalance can be explained by the theme at stake, presented to the interviewees as “citizens' views about French politics.” This can be intimidating for individuals lacking interest in politics and coming from a social and educational background who tend to lack a “sense of empowerment” in expressing opinions about the political world (Gaxie, 2007). By contrast, the sample of Yellow Vests interviewed is less educated, and more of them belong to working class backgrounds. In both samples, individuals self-identifying with the left are over-represented, which can be partly explained by fact that interviews were conducted face-to-face (Mayer, 2018) and by the over-representation of politicized individuals. Around a third of interviewees in both samples did not situate themselves ideologically during the interview, and 56% of our interviewees never had any political engagement (involvement in social movements, political associations, trade unions, parties, etc.). We did our best to diversify the profile of the interviewees to reach respondents who were distant from politics and who were closer to the right and the center. In both samples, we followed the principle of data saturation and planned interviews until no additional information was provided by new interviews (Ando et al., 2014).

The interviews lasted between 40 min and 2 h and 45 min. First, we asked a series of questions to understand their social and professional background, their current news habits, their political socialization and their views about the most recent elections (the 2017 French presidential election and the 2019 European election for the Yellow Vests interviewees). This part aimed at characterizing the social and political background of the interviewee. In the second part, we focused on their conceptions of the political system: feelings about politics, the French political system, the ideal political system and the reforms that should be put in place. Finally, in the third and final part, interviewewees were presented vignettes of institutional reforms adopted in France or other countries and were asked to react about them. These reforms were chosen as ideal-typical reforms embodying various visions of democracy uncovered by political theory: direct democracy controlled by citizens (through recall votes in the US), deliberative democracy (through the citizens' assembly organized in Ireland since 2016), stealth democracy giving power to unelected experts (through the Autorité de la concurrence in France or technocratic governments in Italy) and representative democracy (through gender quotas reforms to promote women in politics in France).

All interviews have been fully transcribed verbatim and coded manually and inductively using the Nvivo qualitative analysis software, in order to identify and analyze the themes spontaneously evoked by interviewees when presented with the topic (see Supplementary Appendix 1 for a detailed presentation of the coding process). The codes were reviewed several times in order to make them consistent and stabilized. The same segment could refer to various themes at once. The codes were regrouped into overarching themes that are the ones used in this article to analyze the conceptions of citizens about their political system: the conception of politics, the evaluation of elected representatives, the conception of the political process and the conception of policy outputs.

We identify four ideal-typical discourses corresponding to four fundamental aspirations: one valuing entrustment to competent individuals above partisan considerations, one valuing participation of ordinary citizens in every step of the political process, one valuing identification and representatives who look like the general population and finally one discourse focusing on control and sanction of existing representatives. These four discourses should not be understood as rigid categories, but rather as contrasting aspirations among which citizens “navigate” when they verbalize their vision of what their political system is and ought to be. Citizens do have ambiguous and sometimes contradictory and opposite aspirations when it comes to the political system. As argued by Ewick and Silbey, “in order for something to be meaningful at all, it must contain, at least implicitly, an opposing or contrasting meaning” (Ewick and Silbey, 1998, 52).

In the following sections, we will discuss in turn the conception of politics, of the political representatives, of the political process and of policy outputs formulated by the interviewees.

Some individuals formulate discourses that are “closer” to the ideal-typical aspirations identified, and can be considered as paragons. We will examine the social background and the political socialization of these paragons, which give us interesting indications about the typical profile related to each of the four aspirations.

The Aspiration to Entrustment

Conception of Politics

In the first discourse we identified, the adversarial and ideological character of politics is criticized as a diversion. Partisanship is rejected, with the implicit idea that it is possible to reach objective and universally acceptable solutions, very much in line with the “stealth aspirations” identified by several authors (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2002; Clarke et al., 2018). Lin1 (female, 38, unemployed) argues:

“I don't like discourses involving too much the notion of conflict. (…) Everyone sticks to his guns, instead of thinking together about what we could do to, say, maximize advantages and limit drawbacks. Anyway, for me, political choices are only about this. It is about mediation. It's about picking the least worst or the best”.

Good politics is associated with harmony, pragmatism, or even truth. For instance, Fabien (male, 38, winegrower) dislikes political debates on TV, because “as long as one does not face the truth, one cannot solve an issue.” In this perspective in which one believes in the possibility to reach an acceptable, dispassionate and depoliticized agreement, politics mainly plays a role of guarantor preserving everyone's liberties. Christophe (male, 23, political science student) argues that:

“Politics shouldn't meddle in everything, quite the contrary. (…) Politics is law. It's people who must make laws to make sure that life in society goes on as well as possible. (…) Make sure things work, that's it. It's like a waiter when you're in a restaurant. It's very important that he's there but you should not see him”.

Vision of Political Representatives

This conception of politics is related with an ideal vision of what political representatives should be like. Politicians should have exceptional qualities that put them aside from the mass of ordinary citizens. Politicians should be knowledgeable, master the art of talk and reject demagogy. This elitist conception of politicians is in line with the analysis of Manin about the inherently aristocratic nature of representative democracy which denotes “the lack of similarity between electors and elected” (Manin, 1997, 159). Lin (38, female, unemployed) draws a distinction between “statesmen” and politicians. According to her,

“A statesman should be aware that everything he says, or everything he does will have an impact on the lives of many people. And even beyond, for future generations. (…) If a politician tells you that it is simple to be a politician, I think he does a very bad job!”

Another interviewee, Christian (71, male, former army colonel) underlines the many qualities he considers as indispensible to become president of the Republic: a good knowledge of French history, of economy, of public law, and a thorough general culture. His discourse refers to many French political personalities from Charles de Gaulle to François Fillon, Alain Juppé, Nicolas Sarkozy, Valery Giscard d'Estaing or Benoît Hamon, who are evaluated and dissected. He also refers to physical attitudes making people apt for the presidential function, underlying the necessity to have not only a mastery of the mind, but also of the body. For instance, talking about the debate opposing the right-wing contenders during the primary in autumn 2016 to select the presidential candidate, he said:

“Juppé drooled, at one point. And my friends (…) said, ‘seeing a man who is not able to make a discourse without drooling, for me, this means that he's unreliable, he can't become president of the Republic!”

In other words, not everyone can (or at least, should) become a politician: only particularly gifted individuals should take this path. This can be related with findings of Clarke et al. who show that British citizens after the WWII expected politicians to be true statesmen, allying moderation, competence, sincerity, and leadership (Clarke et al., 2018).

Vision of the Political Process

In this discourse focusing on the entrustment of political decisions to particularly skilled individuals, the ideal political process is a system guaranteeing efficiency, stability, the ability to reform and the competency of those who take part in the political process. Interviewees proposed various reforms such as the suppression of useless levels of government, the cut of the number of representatives, the installment of a Senate composed exclusively of people who have studied law, or a 7-year term for the president of the Republic to give him more “political height.” More generally, this discourse emphasized the need tend to defend the existing institutional status quo of the Fifth Republic, praising the ability of the current regime to “reform” against so-called conservative forces. For instance, Marion (25, female, lawyer in a hospital) defends the article 49.3 enabling the government to pass a law without a vote if there is no motion of no-confidence adopted with the following arguments: “there are decisions which should be taken rapidly.” The stability of the regime is attributed to the current French constitution, and stability is used as the standard meter to evaluate the current political procedures.

Interviewees who held this discourse often formulate harsh judgments about their fellow citizens, considering that “the problem is not so much the political system, it's people!” (Alexia, 20, female, student in an engineering school). They argue that citizens have unrealistic demands toward politics which could create chaos and instability. Laws and policy-making is considered as “too complex” to allow the participation of lay citizens in the political process. Politicians in general and the President of the Republic in particular should be beyond partisan and vote-seeking considerations and embody the solemnity attached to the presidential function. More generally, in this discourse, interviewees support the existing procedures as long as they “work.” Christophe (23, male, political science student) argues: “whether one agrees with the way it works, this is a different problem. In any case, it works.” This implies, for instance, in the French case, the defense of the two-round majoritarian electoral system which limits the representation of small parties but facilitates the emergence of a strong parliamentary majority. More generally, the judgment of these interviewees on existing French institutions is in line with the dominant discourse of constitutional lawyers and political representatives on the Fifth Republic who strongly value the stability it has supposedly brought to the country.

Vision of Policy Outputs

This discourse values the search for a “middle ground” between interventionism and liberalism, in order to guarantee everyone a minimum quality of living. For instance, Lin (38, female, unemployed), argues:

“I think that ideally, the State should provide its citizens a space of life in which they have the freedom and the affluence to feed themselves, to have proper housing, to move about, and to create businesses”.

Public policies are therefore mere providers of social and economic safety nets. The emphasis is put on individual freedom. The French State is judged as too costly, “too generous and too social” (Christian, male, 71, former military officer) and other citizens as prone to “abuse” the generosity of the State. This goes hand in hand with the notion of “managerial,” or “steering state” coined by specialists of public policy (Clarke and Newman, 1997; Bezès, 2007).

Paragon

Christian is the interviewee who best typifies this aspiration to entrustment in our sample. He is born in 1946 and is a former army colonel. After having studied in a French military high school and embraced a military career, he studied law and developed a strong interest for political matters. Christian comes from a middle-class background: his father was in the army before becoming an insurance broker, and his mother worked for him as a secretary after having been a housewife. He defines his father as a “Gaullist,” and his mother as “right-wing.” None of them were ever involved in a political organization. Christian follows current affairs closely. He listens to a general interest commercial radio (RTL) everyday, reads regularly several conservative weekly newspapers (Le Point, Valeurs actuelles), and does not like television except for the history channel. He votes at every single election and considers voting as an absolute moral and civic duty, but has never been part of any association, political organization or trade union, or participated in demonstrations.

Christian corresponds well to the archetype of the “allegiant citizen” described by Dalton and Welzel (2014): he is deferent to authority, trusts current institutions, and strongly values conventional forms of political participation. He has a strong interest for politics and a good knowledge of French current affairs, but considers that his role as a citizen is mainly to select apt political leaders. His socialization (in his family, at school, and later in the professional world) revolves around the army, a universe structured by conservative values: authority, leadership and order.

The Aspiration to Participation

Conception of Politics

The second archetypical discourse encountered in our interviews can be thought as the reverse mirror of the first one. It revolves around one fundamental aspiration: participation. In this second discourse, politics refers primarily to “civic life.” For instance, Bruno (male, trainer for a pharmaceutical company, 42) argues: “I think [politics] involves everyone. The life of the municipality, the life of the département, the life of the region, the life of France.” In this perspective, politics is seen as inherently antagonistic, because it involves the confrontation of opposing visions of the common good. These clashing orientations require a thorough debate and the organization of a transparent discussion. Léa (Female, 36, artist) argues that “politics is a time of debate. We can debate about different ideas to reach a compromise.” This idealized vision of politics is often contrasted with what politics actually is, namely a pure quest for power. For Jean-Jacques (male, 69, former German teacher and administrative assistant) politics “is a noble word, (…) which is probably tarnished by the practice of politics as it is done today.” Strikingly, this vision of politics is closely related to arguments developed in political theory by authors focusing on pluralism who argue that politics is a space of confrontation and negotiation between opposing interests in order to reach a compromise (Bellamy, 2002, 2012). These interviewees fully recognize the pluralistic nature of politics and democracy (Dahl, 1971).

Vision of Political Representatives

In this discourse, the main issue about politicians is the confiscation of power associated with the professionalization of politics. For Jean (male, 75, former English teacher) politics is “a cast, a court. (…) People coopting each other, people who have power thanks to their relations”. These interviewees refuse the idea that all politicians are inherently corrupted, but consider that corruption is the consequence of the monopolization of power by a few individuals. According to Bruno (male, 42, trainer in a pharmaceutical company), “politics should not be a profession. It should be a personal engagement for the collective good limited in time and widely distributed. Once we do that, I think that rotten politics will no longer exist.” Interviewees also expect politicians to have strong convictions, integrity, and to connect with ordinary people in order to defend their ideas. Personalization of politics and eloquent speakers are rejected. According to André (male, 65, former music teacher):

“Politicians should become amateurs, that's it! And not only people who went to the right school, the ENA,2 schools in which they have been a bit brainwashed (…) At school they're taught that… One should not express doubts. (…) You ask a question, and there is always an answer coming out.”

For Marie-Paule (female, 55, archeologist), politicians should be “normal people. Who are not pure egos. Who do not put their ego on the front, who are there for a function.” In other words, politics should not be a profession, but a function, in which politicians are not exceptional individuals, but rather ordinary people temporarily engaged in a collective enterprise for the common good.

Vision of the Political Process

Logically following from this rejection of professionalization and personalization, political institutions are conceived as means to facilitate the de-personalization of the political process and the inclusion of citizens in decision-making. Some interviewees support the recognition of blank votes, others defend proportional representation, compulsory voting, participatory mechanisms, other still the development of checks and balances in the French political system or political education in secondary schools. These aspirations are put in perspective with the current functioning of the French political system, perceived as a “Republican monarchy”, not inclusive, too personalized and lacking transparency. For instance, Jean (75, male, former English teacher) despises a system characterized by “opacity (…) There are rooms without doors and without windows, with a secret code. And only the holders of the code can enter”.

All of these reforms are seen as means to guarantee inclusion, horizontality, proximity, transparency, and the reversal of the symbolic power between elected politicians and citizens. The political process is seen as having the potential of being an emancipatory instance. Citizens are seen as universally competent, and procedures should ensure that decisions emerge collectively. Solange (69, female, former biologist) argues:

“I think we're always less stupid when several people are involved. (…) There are plenty of people who have an opinion! But there are people who don't dare talking. And those who say: ‘if you don't have the right words, you shouldn't speak'. That's part of what I call popular education. (…) [Politics] can be taught, it's like everything.”

This inclusive discourse is strongly associated with the local level, perceived as a relevant political scale for citizens to become political actors on a day to day basis. Léa (36, female, artist) describes her ideal system as one “starting from the principle that we can be actors locally.”

Vision of Policy Outputs

In this discourse, politics is seen as an instrument of social progress and equity. These interviewees relate the professionalization of politics and the confiscation of power with the implementation of policies that only benefit specific and privileged groups. For instance, Jean-Jacques (69, former German teacher) criticizes harshly the fact that “politics is more and more done by lobbies and CEOs in France and elsewhere.” The policies advocated relate to welfare, public service, education, health or the environment, always with the idea that politics is an instrument of collective progress. Taxes are seen as necessary and positive, as they are the main resource allowing for social progress. At the same time, the interviewees who held this discourse often regretted the fact that the French welfare state was being dismantled, and criticized the rise of social inequalities. Elise (female, 69, former snack and bar tender) said to me: “Why don't we do anything? Why is the gap getting larger? We must change the world! (…) All the social progress earned by class struggle, this social progress is gone. Definitively gone.” The aspiration to inclusion and participation relates, in terms of public policies, to the support for policies promoting social equality and the collective good more generally.

Paragon

Solange (69, former biologist) is the best archetypical example of this aspiration to participation. Born in 1948, she obtained a PhD in 1978 and worked as a research engineer. She has experienced a strong ascending social mobility as she comes from a working-class background: her father was a cabinetmaker and her mother a seamstress. Her media habits are typical of the intellectual and highly politicized individuals (Le Hay et al., 2011). She reads Libération (a national left-leaning daily newspaper) everyday, but she has also been a subscriber of Le Monde (the most prestigious daily newspaper in France) or Le Monde diplomatique (a monthly newspaper gathering many left-wing contributions). She does not own a television, defines herself as an “all-time adept of France Culture” (an intellectual public radio channel) and is an avid reader of political and economic essays. She started her political engagement by joining the CFDT3 in the 1970s as she felt close to the PSU (Socialist Unified Party, a self-managed political party)4. She has been part of multiple political associations: ATTAC (Association for the Taxation of financial Transactions and citizens' action), an association for the recognition of blank ballots, or the International League for Human rights. During the interview, she situates herself very precisely in the intricacies of the French political left. She votes systematically at every election, often attends local political meetings, and has taken part in various demonstrations.

To use Dalton and Welzel's typology again, Solange is the embodiment of the “assertive citizen” (2014). She values and practices very diverse forms of political activities, distrust authorities, strongly believes in the virtues of inclusion and participation and is very critical of existing French political institutions. Her interest in politics and her participatory conception of the political system was built over time in self-managed and highly politicized circles, in particular thanks to her trade union activities which led her to various other forms of political engagement on the left and made her particularly politically competent.

The Aspiration to Identification

Conception of Politics

The third discourse could be summarized by the aspiration to identification, that is to say the will to have representatives who share characteristics with oneself. In the first two archetypical discourses presented above, politics is seen as a potentially positive force, with the ability to affect people's lives. In the third discourse, on the contrary, politics is associated with vanity, uselessness and ridiculousness. It lacks any concreteness and has no hold over people's lives. According to Arthur (male, 20, unemployed): “a lousy politician in government has never changed a thing.” Consequently, in this perspective, citizens refuse to place any hope or expectations into politics. Talking about the last presidential elections, Basile (male, 24, designer) argues:

“I could never imagine that all of these promises could one day spill over onto me, or my closed ones, or the real life of people. (…) [Politics] bores me. It bores me, because it's a lot of efforts for nothing. It's like tilting at windmills”.

Vision of Political Representatives

Interviewees holding this third discourse judge politicians primarily by comparing their socio-demographic characteristics with the characteristics of the general population and their own characteristics, noting the gap existing between the two categories. Current politicians are considered as identical, interchangeable, in politics for too long, or even “redundant.” Elected politicians should resemble the general population, because individuals from a certain group are better suited to represent the interests of a specific segment of the people.

This idea goes hand in hand with the notion of “descriptive representation” coined by Pitkin, who argued that “a representative body is distinguished by an accurate correspondence or resemblance to what it represents, by reflecting without distortion” (Pitkin, 1967, 60). According to Faly (22, male, student in a business school) politicians are “the vast majority of the time people who have a certain age, who have been in politics for a while. So, from a physical point of view, yes, they all sort of lookalike (…) they are almost redundant.” Talking about the qualities he sees in Emmanuel Macron, he argues “what attracted me is the fact that he is young. And therefore, for me, a young president is a good point because (…) I am fed up of seeing always the same faces.” By contrast, another interviewee (Arthur, 20, male, unemployed) with working class origins strongly rejects Macron because “he is a banker.” He voted for Philippe Poutou5 “because he is a worker, so he knows what a factory is.” These two interviewees project certain desirable characteristics (age for the former, or social class for the latter) in order to reach a positive or negative judgment about given politicians.

Vision of the Political Process

As good institutions ensure that political representation is a mirror of society, interviewees support reforms in favor of the social, generational and sometimes ethnic diversification of elected representatives. This is in direct opposition with the first aspiration in which competence and stability should prevail over considerations such as representativeness and diversity. Manon (23, female, student in a nursing school), makes the following argument:

“Getting interested [in politics] is complicated, because when we try we realize that people who do politics have nothing to do with us (…) Because someone talking about immigration, or this, or that, but who has all of his life lived in beautiful houses, with a lot of money, we wonder, ‘but what does he know exactly?”

Diversity is seen as a gateway to diffuse various personal experiences into the political debate, with the idea that the common interest and the legitimacy of the political process are linked with the ability of the institutions to encompass and aggregate diversity. Basile (male, 24, designer) defends a system in which people from different social backgrounds could enter politics, in order to reconnect citizens with politics. He considers that the root of political disenchantment is due to the lack of diversity: “Social diversity would enable people to identify themselves. (…) It would give us many more different ways of thinking.” According to their own socio-demographic characteristics, some insisted more on social diversity, some on the over-representation of older people, or on the lack of representatives with foreign origins. For example, Amine (21, male, unemployed), who is originally from Maghreb, says that “it would be good if there were not only French people in the parliament.” These interviewees consider that when someone has not experienced concretely a given situation, she is not able to elaborate good public policies. More generally, a good political system is a system in which individuals are legitimate because they have various personal backgrounds enabling them to take political decisions rooted on personal experience. Jane Mansbridge formulates a similar argument and argues that descriptive representation improves the quality of decision and deliberation and the legitimacy of the polity. She also considers also that descriptive representation can be understood not only as visible characteristics (being a woman, or being black for instance) but mostly as shared experiences (Mansbridge, 1999).

Vision of Policy Outputs

In the two previous conceptions, interviewees evaluated public policies by providing a general discourse on the general interest rather than relying on the evaluation of their own personal situation. Here, by contrast, the evaluation of policy outputs is based first and foremost on the perception that the State does too little for the social, ethnic or generational group one belongs too. As the political system only represents certain people, it also only provide policies and public services for certain segments of the population to the expense of other groups that do not have access to public decision—a belief that is, in fact, quite supported by empirical evidence (Bartels, 2018). For instance, Arthur (20, male, unemployed), who is a young unemployed working-class boy wants “economic change, employment. (…) Those who are concerned with unemployment are people my age. From 18 to 25 years old.” Other interviewees also refer to their “generation”: for instance, Basile (male, 24, designer), argues “we feel, our generation, that we have the all the bad sides.” He agrees with the idea of paying taxes in principle but that he feels that other groups benefit from it, and he and his generation do not. Maelys (24, female, administrative assistant) also reproaches the French welfare state not to provide financial aids catered to people in her own situation: she graduated and is not entitled to any financial help before turning 25. Faly (22, male, student in a business school, who is black) says he sometimes feels like a “sub-French” and considers that France is not supportive enough of its ethnic and religious diversity. More generally, these young interviewees advocated for policies addressed specifically at them. They evaluate policies based on egotropic considerations rather than sociotropic ones, to use a concept of economic voting.

Paragon

Basile is the most archetypical example of this discourse. Born in 1993, he comes from Paris and has a Higher National diploma in interior design. He started his first stable job one year before and still lives with his father (his parents are divorced). His mother is a teacher in a professional high school, and his father never really had a stable professional situation. He comes from a leftist and politicized family: his mother in particular is involved in Unbowed France and was part of a trade union during all of her career. Several of his relatives were communists. Basile clearly defines himself as left-wing and mentions demonstrations, strikes and sit-ins in which he took part when he was in high school. He is therefore clearly able to situate himself politically and is quite knowledgeable about politics. Despite this background, Basile is less and less interested in politics since he has started working. He used to read Le Monde on his smartphone, but uninstalled the app, and occasionally flips through newspapers that he finds at work. He does not have a TV and never listens to the radio. He votes very intermittently as he considers that elections do not change anything. He is not part of any political organization and justifies what he calls his own “individualism” by the powerlessness he feels about politics.

What dominates in Basile's interview is the discrepancy between his leftist convictions, his politicized environment, and the rapid loss of interest for political matters. This interview also reveals the deep-seated gap between what Basile expects from the political system and his perception of what it actually is, which leads to political apathy even if he comes from an environment making him predisposed to political engagement.

The Aspiration to Control and Sanction

Citizens closer to this fourth and final discourse are particularly distant from formal politics which makes interviews about political questions quite difficult. Lay citizens who were closer to this discourse did express clear criticisms about the current system, but did not have very precise attitudes on the reforms that were needed. It is the reason why this fourth discourse can also be informed by the interviews done with a peculiar group of Yellow Vests: those who got involved for the very first time in a social movement. Indeed, these interviewees also used to share the idea that politics is an estranged world, but eventually joined the movement anyway and develop a structured discourse about their vision of the political system and their institutional aspirations (Bedock et al., 2020). Their discourses enable us to inform the attitudes of citizens who are distant from formal politics about the political system.

Vision of Politics

The fourth discourse is the one that involves the most negative vision of politics and political representatives. Politics is seen as a physically separate space, with its own impenetrable language. Citizens feel uninvolved as in the previous discourse, but more fundamentally, they are profoundly apart from a political world they do not understand, frequently using metaphors relating to physical distance. The strong disinterest for politics is linked with a perceived inability to decipher political discussions. With Jessica (female, 27, farm worker), I have the following discussion when I ask her what politics is about.

- “- J: Pffffffffft. It does not interest me at all in fact! No, not at all.

- Me: Why doesn't it interest you?

- J: I don't know, it doesn't attract me…. First, I understand nothing. I tried, when there were the elections and so on, I tried to have a look but I understand strictly nothing. (…) It's their way of talking, of developing and so on, really too… Too much into their own language, I don't know if you see what I mean.

- Me: Yes, as if there were talking to themselves, or…

- J: Yes, that's it, exactly”.

As a consequence, politics only relates to a few familiar characters, such as Emmanuel Macron or Marine Le Pen, but is just not part of everyday life. As Daniel Gaxie argued, “for categories weakly concerned by political questions (…) the feelings of misunderstanding and incompetence are mutually reinforcing and lead to self-disqualification” (Gaxie, 2007, 750).

Vision of Political Representatives

Politicians are perceived as an undifferentiated group benefiting from unjustifiable privileges, apart from the general population, and not living like ordinary people. The opposition between “us” (the people) and “them” (all politicians) is particularly pregnant, and refers to the inability of politicians to understand the ordinary conditions of most citizens because they inhabit “different spheres” (Clément, 40, male, builder). Politicians are seen as rich, bourgeois, disconnected, privileged, and corrupted. Still according to Jessica:

“[Politicians] are in their world. (…) They don't live like us. They should put themselves in our shoes (…) I think they have not experienced the same miseries as us. For us, there are times at the end of the month when we have trouble feeding ourselves, but they don't have this problem. (…) They are too much into their little bubble of rich people, of posh people. (…) They're born with a silver spoon”.

Behind this discourse lies the idea that politicians are not able to have empathy for “us,” the “people,” understood as a totalizing unit. Politicians are presented as completely socially homogenous, equally guilty and corrupted. This generalizing discourse is often “borrowed” from other people rather than fully incorporated by interviewees who tend to set themselves aside from politics. For instance, Gabin (20, male, waiter) tells me:

- “G: My relatives complain a lot. So I have a bad opinion because of that.

- Me: What do they complain about?

- G.: That the system is rotten. Really rotten. That's what comes out. (…)

- Me: Rotten in the sense… In what sense, do you know?

- G.: Sort of, but that's difficult to explain”.

The privileges of elected representatives—whether real, or fantasized—are heavily criticized. For instance, Jean-Louis (69, involved in the Yellow Vests and former skilled-worker) tells us that “If I had been a politician, I would drive a Rolls Royce (…) I would make 10.000 euros a month!”

Vision of the Political Process

The interviewees who expressed the strongest disinterest for politics did not to formulate very precise expectations about the necessary reforms of the political system, but were overwhelmingly positive when ideas such as recall and direct democracy controlled by the citizens themselves are being discussed at the end of the interviews. The privileges associated with the elected function are seen as unbearable, undeserved, and aggravating the gap between the political class and ordinary citizens. The comparison between politicians and ordinary workers is often mentioned, in particular when we discussed recall. The threat of recall is seen as particularly positive, because it would turn politicians into ordinary workers who could be “fired” when they misbehave. Aurélien (male, 24, unemployed) argues that “they would work much more,” Fabien (38, male, winemaker) that “if I hire an employee and he does a bad job, I fire him.” Interviewees expect the political system to give them the possibility to control and sanction politicians and to prevent them from becoming a separate, lazy, privileged and often corrupt cast. The logical consequence of this generalized suspicion is the will to punish politicians who abuse their position of power when they are not held accountable by castigatory mechanisms. Direct democracy is not understood as a tool of permanent citizen participation, but rather as something that should be used punctually either to punish politicians while keeping a rather distant relationship to politics.

Yellow Vests activists' discourses help us to better understand what lies behind this will to control and sanction elected representatives. Recall and direct democracy are mentioned spontaneously by all of the Yellow Vests interviewed, as they are part of the demands of the Yellow Vests movement (Collectif d'enquête sur les Gilets jaunes, 2019). Despite the severity of the judgment made about elected politicians, these interviewees do not wish to do without them. The idea to delegate one's political power to elected politicians is accepted, but under very strict conditions: political mandates should be binding thanks to recall mechanisms to make politicians truly accountable (see Vandamme on recall in this research topic), representatives should seek to represent the general will of the people, and they should have not only a physical, but also a statutory proximity with their voters (Bedock et al., 2020). This statutory proximity involves a “normal” salary and the absence of privileges attached to the political sanction, but also the possibility to be “fired.” In other words, representatives are conceived as simple delegates of “the people” who should be made accountable through recall mechanisms (Marx, 1871; Cronin, 1990).

Vision of Policy Outputs

In this final discourse, interviewees feel that existing policies drag down “the people” as a whole. The politicians are considered as an elite with unlimited rights, that wastes people's money and uses policies to strengthen its privileges. Talking about politicians, Cathy (49, female, medical secretary) argues that “they help themselves!” which prevents them from having in mind the interests of the people. These interviewees also resent what they perceive as a decline of the country, in which everything is more expensive, more difficult, in which they feel less and less secure and more and more excluded. Jessica (21, female, farm worker) mentions immigration, terrorism, the high cost of living in a discourse in which a diffuse fear of the future shows through. She expresses a deep pessimism about the future of her country: “the more it goes, the less we will have, France will be penniless, it will be really…We will really have nothing anymore.” Mentioning the social benefits granted to immigrants according to a Facebook post she saw, she is convinced that politicians have organized a system in which some groups are granted more rights than “normal people.”

Again, the opposition between “we” and “us” is structuring the discourse, “us” referring to self-serving politicians, or to immigrants, and more generally to social entities opposed to “the people.” This discourse very much resonates with the “stealth populist” discourse which portrays “an incompetent and out-of-touch political elite (who act, the story goes, against the interests of the people” (Clarke et al., 2018, 262).

Paragon

Jessica is the archetypical examples of this fourth and final discourse. Born in 1990, she left school when she was 16 without any diploma. She has worked as a farm worker in vineyards for more than 10 years. She comes from a small and impoverished city and has never lived elsewhere. Jessica is a single mom. Her mother used to be a cleaning lady and her father a stonemason. She does not follow political issues and Facebook is her only source of information. She has never voted in any election. Jessica and all of her relatives have never been involved in any political organization, or participated in any political or social movements. Her socialization made Jessica particularly impervious to politics: she does not have a diploma and her family has always kept politics at arm's length. Her social situation is particularly difficult: she has a very physical, demanding and low-paid seasonal job, and is obligated to rely on her parents and on employment benefits to raise her daughter. She has no professional perspective and perceives this situation as fundamentally unfair. As a result, she rejects all individuals and groups that appear to take advantage of people like her.

Conclusion and Discussion

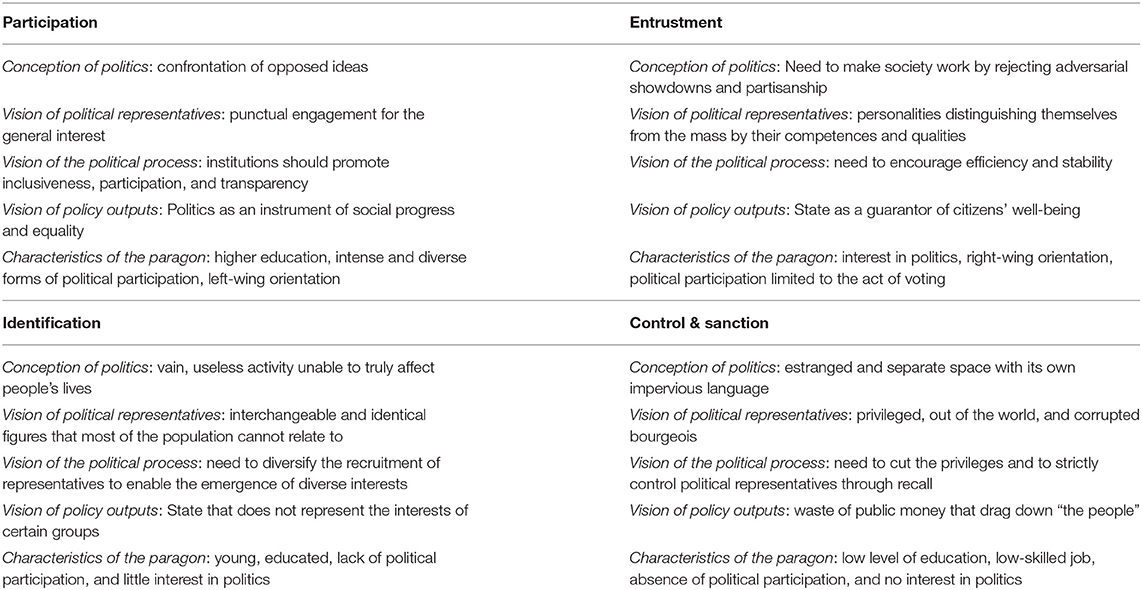

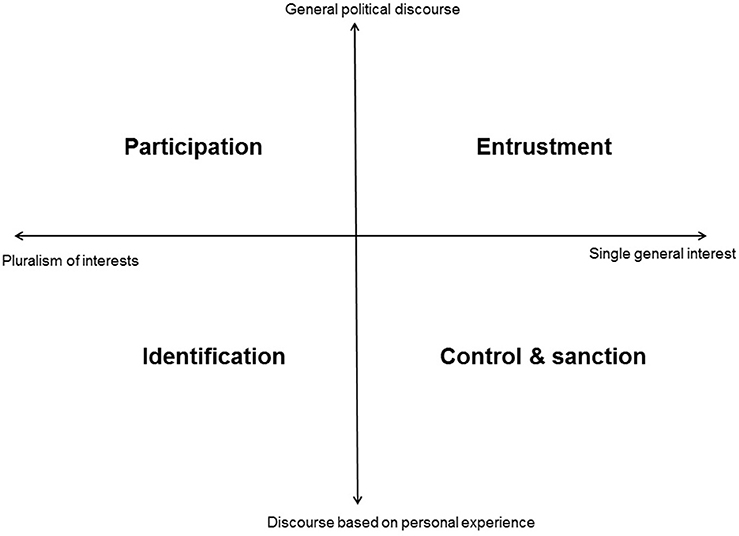

Table 1 summarizes our findings and the four aspirations expressed by French citizens about their political system. Two oppositions structure these four aspirations (see Figure 1). The first structuring dimension concerns the level of politicization of individuals, intended here as the ability to formulate general discourses and to enunciate general political principles (Hamidi, 2006). In the participation and in the entrustment aspirations, individuals formulate discourses based on general principles. Similarly, in these two discourses, interviewees formulate expectations about their political ideals. They do not refer to their own personal experience to formulate these ideals, but to moral and political values that should guide political action. By contrast, in the identification and in the control & sanction aspirations, interviewees base their judgments about the political system on their personal experience. A fair political system should do more for people in their situation. When they refer to political representatives, they criticize them and express a negative judgment, but they do not refer explicitly to the ideal qualities that political representatives should have.

The ability to formulate general discourses appears to be linked with the level of political participation and involvement in public affairs. The description of the four paragons shows that the main political characteristic enabling to differentiate between the four discourses is the intensity and the nature of political participation. Political orientation also matters. Individuals who use various forms of political participation to express themselves (vote, but also demonstrations, activism in political organizations, etc.) and who are left-leaning tend to be much closer to the participation discourse. Those who are politically interested, who limit their participation to elections and situate themselves to the center or to the right are closer to the entrustment discourse. By contrast, individuals who express the identification and control & sanction aspirations have a low level of political interest and involvement. What differentiates them is their level of education and their social position: individuals who are closer to the identification discourse are overall more educated, whereas interviewees who express the most bluntly the aspiration to control & sanction are characterized by a low level of education and low-skilled jobs.

The second structuring dimension relates to the conception of the general interest. It opposes the participation and the identification aspirations that acknowledge “the plurality of reals” (Laski, 1917, 9) that should be accommodated in the political system and the entrustment and control & sanction aspirations that have a unitary and non-pluralist vision of the general interest. The aspirations to participation and to identification are based on the belief that individuals have multiple and opposed interests based on their social background and life experience. On the contrary, the aspirations to entrustment and control & sanction have one thing in common: the belief that “there are things that are either good or bad for the whole of society and political action can be either good or bad for a society in its entirety” (Caramani, 2017, 60). Those who were closer to the entrustment aspiration consider that general interest can be achieved by delegating political power to competent, a-partisan and moderate statesmen, whereas those who were closer to the control & sanction discourse consider that general interest can be achieved by having the ability to punish political elites.

What is particularly striking in our inquiry is the fact that the discourses of French citizens revolve very much around the different logics of political representation, even though our research design dealt with the vision of the political system in general. Several citizens did not express very precise expectations or ideas about the institutional organization of the country—such as the electoral system, the balance of power between the executive and the legislative power, or the vertical organization of powers. This does not mean, however, that they did not have opinions about the political system: rather, these attitudes and discourses were structured by a more general reflection on the modalities of delegation of political power. All citizens we met implicitly or explicitly agree with the idea that political power should be delegated to representatives, but they had different visions about what this representative should do or look like. Political representation remains inescapable in the minds of our interviewees. This result was unexpected, as there is a heated debate in empirical and theoretical political science about the idea that political representation could be bypassed.

Each of the four ideal-typical discourses can be related with a vision of political representation discussed in political theory. Pettit underlines the existence of three types of representatives which can be related with three out of the four discourses: trustees, delegates, and proxies. Trustees are representatives who speak with authority for another, with the freedom to take their own political decisions with no direct control of the represented (Pettit, 2009). As underlined by Manin (1997), the representative government draws its legitimacy from the superiority of the representatives over the represented. This first vision of political representation closely resembles the entrustment discourse. Delegates can be compared with attorneys who act for their clients with the explicit or implicit direction of the represented. As Pettit underlines, “the control that the people exercise over such public representers may take an active, hands-on form, as when the representees impose suitable constraints on representers or give them explicit instructions. But it may often be just virtual in character, constituting a sort of hands-off, arm's length control” (Pettit, 2009, 72). This vision of political representation closely resembles the aspiration for control & sanction. These two first conceptions of representation implicitly imply that representatives are able to represent a single general interest, either because they use their authority to take the best political decisions, or because they are supposed to implement the putative “will of the people” (Caramani, 2017).

Proxies are representatives who stand for the represented in the sense of epitomizing them (Pettit, 2009): their legitimacy stems from the fact that they act in the same way as the represented would, because they share characteristics and life experiences with them. This conception of representation shows through in the identification discourse. Finally, we can discuss a fourth conception of representation that is closer to the one expressed by interviewees in the participation discourse. It focuses on the link between electoral and non-electoral forms of representation. As underlined by Saward and others, representation is a process of making, accepting or rejecting representative claims (Saward, 2010; Guasti and Geissel, 2019a,b). Representation cannot be reduced to elections and to the action of political representatives, but also takes place in multiple other settings: citizens' assemblies, social movements, various political and non-political organizations, etc. In the participation discourse, interviewees do not want to get rid of electoral representation which remains the cornerstone of the political system, but they reflect upon the way in which citizens could be part of the political process not only during elections, but also more generally. Political representatives do not have the monopoly of representation and political decisions and representation is therefore understood as a more fluid process. These last two conceptions of representation rely on the idea that society is composed of multiple interests, and that the role of political representatives is to channel these diverse interests.

These results are, of course, exploratory in nature and rooted in the French context. As already underlined, France is a majoritarian, strongly adversarial semi-presidential democracy dominated by the figure of the President of the Republic. It leaves few opportunities for citizens to participate outside of elections. Parties, trade unions and other organizations are relatively weak compared to most West European countries, and French citizens are particularly critical of their existing institutions. In our analysis, three out of the four archetypical discourses identified express deep-seated criticisms about the functioning of French democracy. Our results largely echo previous findings in the UK (Stoker and Hay, 2017; Clarke et al., 2018) which may suggest that citizens in majoritarian democracies share similar views about their political system. Citizens in other national settings may be less severe and formulate alternative discourses. Saunders et al. note the importance of taking into account the institutional and political context when analyzing the conceptions of politics and democracy of lay citizens (2019). Existing studies, both quantitative and qualitative, suggest in particular that citizens in consensual democracies—that Lijphart famously qualified as “kindler and gentler” democracies Lijphart (1999)–have a more positive view of their political system, in particular when direct democratic procedures are in place (Ferrin and Kriesi, 2016; Saunders and Klandermans, 2019). For instance, Swiss citizens stand out because of their positive overview about their political system and the limited prevalence of anti-politics feelings. Future works should explore the impact of the national context on citizens' contrasting aspirations about their political system.

I used individual interviews in order to explore the discourses of lay citizens about their political system. Most qualitative studies on similar topics use focus groups, which are ideal to analyze the effect of context, group composition and group dynamics on the production of a shared understanding about a given topic. Individual interviews cannot achieve this, but enable to better understand the strong variations of the discourses of lay citizens and how these discourses are related to their social and political characteristics. This choice has enabled to pinpoint some of the limitations of the existing literature. For instance, the opposition between expertise and political representation, which has been underlined in many existing studies, is in fact a bit of a false opposition. There is no evidence in our qualitative interviews that individuals wish to make technocracy the guiding principle in the political system by replacing politicians by experts. However, several of our interviewees—those who aspire to entrustment–do share the belief that politics should be a-partisan and give more weight to competent, but elected, individuals, in particular when they believe that a consensus can be found on the general interest (Medvic, 2019). The opposition between representation and expertise (Bengtsson and Christensen, 2016) may relate to the evaluation of current politicians, but does not appear to express a true aspiration for non-elected technocracy, confirming a diagnosis already made in the UK (Clarke et al., 2018).

Most of the existing studies have identified the opposition between the aspiration to political participation and the aspiration to entrustment. For instance, Dalton and Welzel talked about the opposition between allegiant and assertive citizens (2014) to describe the shift from citizens who value current forms of political participation and those who want to participate more intensely. It is quite striking that the aspirations to identification and control & punishment have been much less discussed in the existing literature. Pitkin had already pointed out the concept of descriptive representation (1967), which is key to legitimize democratic reforms such as gender quotas. However, the extent of this aspiration to identification has not been at the center of existing studies on democratic conceptions of the political system. The aspiration to control & sanction, with mechanisms such as recall and delegate forms of political representation has not been thoroughly discussed in empirical contributions, with very few exceptions (Welp and Whitehead, 2020). We argue that these gaps may be due to the very social and political characteristics of individuals who share these two aspirations. Our article suggests that identification and control & sanction are aspirations of individuals who do not participate a lot politically and/or who are socially marginalized. This result is sobering and suggests that political scientists themselves may have biases when they examine citizens' conceptions of the political system, which leads them to pay too little attention to the aspirations of the most marginal individuals in society. Future studies, in particular quantitative and comparative ones, should explore these two aspirations further in order to have a more complete picture of the conceptions of the political system of ordinary citizens in democracies.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The participants provided oral informed consent for the publication of their verbatim quotes, in accordance with national legislation at the time of interview.

Author Contributions

CB has written the article, collected transcribed and coded the 32 interviews with French citizens used as the main material for the article. CB, Tinette Schnatterer, Loïc Bonin and Tinette Schatterer have jointly collected and transcribed the 24 interviews with Yellow Vests used as a complementary material in Section The Aspiration to Control and Sanction of the article. CB and Tinette Schnatterer have coded these 24 interviews.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

CB wants to warmly thank Pierre-Etienne Vandamme, Jean-Benoît Pilet, and Tinette Schnatterer for their careful reading of previous versions of this article and for their stimulating advice. CB warmly thanks Tinette Schnatterer, Loïc Bonin, and Pauline Liochon for their huge contribution to the fieldwork and the coding of the Yellow Vests interviews used as a complementary empirical material in this article.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2020.563351/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The names of the interviewees were changed and replaced by similar surnames in terms of popularity by year and social and ethnic origins, based on the website https://dataaddict.fr/prenoms/.

2. ^National School of Administration. This is one of the most prestigious schools in France, training higher civil servants. A substantial part of the national political class has been trained in this school.

3. ^French Democratic Confederation of Labor.

4. ^As underlined by Bourdieu (1979, 496), supporters of the PSU are typically found among the intellectual class and are characterized by the fact that they see everything through a political prism.

5. ^Philippe Poutou was the candidate of the New Anticapitalist Party in 2017.

References

Ando, H., Cousins, R., and Young, C. (2014). Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: development and refinement of a codebook. Compr. Psychol. 3:3.4. doi: 10.2466/03.CP.3.4

Bartels, L. M. (2018). Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bedock, C. (2017). Reforming Democracy: Institutional Engineering in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198779582.001.0001

Bedock, C., and Pilet, J. (2020). Who supports citizens selected by lot to be the main policymakers? A study of French citizens. 1–20. doi: 10.1017/gov.2020.1

Bedock, C., Bonin, L., Liochon, P., and Schnatterer, T. (2020). Une représentation sous contrôle : visions du système politique et réformes institutionnelles dans le mouvement des gilets jaunes. Participations 2.

Bellamy, R. (2002). Liberalism and Pluralism: Towards a Politics of Compromise. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203007327

Bellamy, R. (2012). Democracy, compromise and the representation paradox: coalition government and political integrity. Gove. Opposit. 47, 441–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2012.01370.x

Bengtsson, Å. (2012). Citizens' perceptions of political processes: a critical evaluation of preference consistency and survey items. Revis. Int. Sociol. 70, 45–64. doi: 10.3989/ris.2012.01.29

Bengtsson, Å., and Christensen, H. S. (2016). Ideals and actions: do citizens' patterns of political participation correspond to their conceptions of democracy? Gove. Opposit. 51, 234–260. doi: 10.1017/gov.2014.29

Bengtsson, Å., and Mattila, M. (2009). Direct democracy and its critics: support for direct democracy and ‘stealth' democracy in Finland. West Eur. Poli. 32, 1031–1048. doi: 10.1080/01402380903065256

Bertsou, E., and Pastorella, G. (2017). Technocratic attitudes: a citizens' perspective of expert decision-making. West Eur. Polit. 40, 430–458. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2016.1242046

Bezès, P. (2007). The “steering state” model: the emergence of a new organizational form in the French public administration. Sociol. Travail 49, e67–e89. doi: 10.1016/j.soctra.2007.10.002

Bowler, S., and Donovan, T. (2019). Perceptions of referendums and democracy: the referendum disappointment gap. Polit. Gov. 7, 227–241. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i2.1874

Bowler, S., Donovan, T., and Karp, J. A. (2007). Enraged or engaged? Preferences for direct citizen participation in affluent democracies. Polit. Res. Q 60, 351–362. doi: 10.1177/1065912907304108

Caluwaerts, D., Biard, B., Jacquet, V., and Reuchamps, M. (2018). “What is a good democracy? Citizens' support for new modes of governing,” in Mind the Gap : Political Participation and Representation in Belgium, ed. K. Deschouwer (Colchester: ECPR Press), 75–90.

Caramani, D. (2017). Will vs. reason: the populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government. Am. Poli. Sci. Rev. 111, 54–67. doi: 10.1017/S0003055416000538

Ceka, B., and Magalhães, P. C. (2020). Do the rich and the poor have different conceptions of democracy? Socioeconomic status, inequality, and the political status quo. Comp. Polit. 52, 383–412. doi: 10.5129/001041520X15670823829196

Clarke, J., and Newman, J. (1997). The Managerial State: Power, Politics and Ideology in the Remaking of Social Welfare. London: SAGE.

Clarke, N., Jennings, W., Moss, J., and Stoker, G. (2018). The Good Politician: Folk Theories, Political Interaction, and the Rise of Anti-Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108641357