- Attallah College of Educational Studies, Thompson Policy Institute on Disability, Chapman University, Orange, CA, United States

In response to the COVID-19 school closures in both K-12 and higher education, a group of education partners in the United States collaborated to offer a statewide webinar series, 12 webinars in total, to support preservice teachers as they worked to complete their clinical hour requirements. The webinars and extension activities provided via Padlets covered topics associated with best practices and related to credential requirements such as applying universal design for learning and differentiating instruction. This study explored the perceptions of 248 preservice teachers regarding the virtual professional learning format and extension activities, as well as what professional learning they felt they needed in the future as they began their first year teaching during COVID-19. Findings suggest preservice teachers were receptive to learning through the structured webinar platform and found extension activities helpful in applying content. Their knowledge, sense of preparedness, and application of the topics and strategies presented increased, and the topics were relevant and supported the required practicum hours and future teaching practice.

The Spring 2020 semester for teacher candidates (also referred to as preservice teachers) conducting their clinical hours in student teaching placements may be the most unique student experience since the practice began. Immediate school closures due to COVID-19 caused schools, teachers, and teacher preparation programs to scramble to figure out how to do everything virtually in a matter of days. In California, as with many places throughout the United States and across the world, teacher education programs had to figure out how to support preservice teachers with meeting the clinical hour requirements for completion of the teaching credential/licensure. This includes student teachers who were no longer able to work with, or had limited access to, the K-12 students in their student teaching placements due to a number of factors including district virtual teaching rules or schools and districts providing at-home packets or work for students in lieu of virtual learning environments.

To provide professional learning and extension activities that may meet the clinical hour requirements, a consortium of partners across the state of California collaborated to offer free professionally prepared webinars to student teachers, university supervisors, mentor teachers, and university faculty. Each webinar was structured using researched methods for engagement and virtual learning retention, employed highly regarded speakers in the field of education, and supported deeper learning through the use of recordings and Padlets. This paper presents results of a study focused on assessing preservice educator perceptions of these professional learning activities and what those educators feel they need to be successful moving into their first year of teaching during a pandemic.

Background

Development and content

In response to the limited access teacher candidates had to classroom settings, due to COVID-19 school closures, the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing [CCTC] (2020) published a resource titled, Guidance for Field Experience in Educator Preparation Programs on COVID-19. Three broad areas emerged from the guiding document:

1. Co-planning with veteran practitioners for lessons the candidate will deliver;

2. Working with professional learning communities and grade level and department teams; and

3. Working with veteran practitioners, grading and analyzing student work, reflecting on lessons, and planning for the needs of individual students.

The CCTC encouraged programs to think broadly and creatively when developing alternatives to some of the clinical practice requirements. We developed an Active Education Webinar Series was developed in response to the adjusted expectations.

By inviting the education community, including institutions of higher education, county offices of education, school district administration, experienced teachers, new teachers, and teacher candidates, the webinars offered the opportunity to co-plan and meet with veteran educators and peers. Extension activities offered opportunities for teacher candidates to continue developing skills beyond the webinar and breakout room. Additionally, the webinars offered teacher candidates the opportunity to accrue hours working in professional learning communities along with other educators across the state. The intentional webinar structure offered the opportunity for teacher candidates to discuss grading practices, analyze student work samples, reflect on lessons, and plan collaboratively to meet the individual needs of students. Extension activities included ideas and links to lesson planning and content area materials, videos, and books for candidates use in collaboration with mentor teachers, university supervisors, or other experienced educators.

The CCTC requires credential programs to provide, in their coursework and through clinical practice, introduction, development, and practice of specified content. This content is articulated in the teaching performance expectations (TPEs), a set of standards that must be met through a performance-based assessment at the culmination of student teaching (California Commission on Teacher Credentialing [CCTC], 2016). Pre-COVID-19, teacher candidates would complete clinical practice, in a classroom setting, during their coursework semesters and in their student teaching practice. With school closures, this clinical practice had to be modified. The intention of the webinars was to provide space for candidates to develop and practice skills needed to apply the learning acquired in their coursework. Topics were selected based on the TPE requirements and included positive behavior supports, culturally responsive teaching, evidence-based literacy practices, universal design for learning (UDL), multitiered system of support, co-teaching, differentiated instruction, and the California Teacher Performance Assessment.

Design aligned with best practices in remote learning

The Active Education Webinar Series was designed to provide engaging virtual professional learning and extension activities to teacher candidates whose student teaching was disrupted due to school closures because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The web-based seminars focused on high access strategies that can be applied by all teachers to reach all students. Research indicates face-to-face learning environments do not seamlessly transfer to the virtual world (Andersen, 2010; Hersh, 2020). The structural characteristics of web-based seminars, commonly known as webinars, are critical for active engagement, collaboration, and learning retention (Frederick, 2011; Yates, 2014; Gschwandtner, 2016; Lieser et al., 2018; Bondie, 2020; Hersh, 2020). The webinars designed are based on research–identified, high–yield practices focused on preparation, presentation, and post-webinar follow up (McBrien et al., 2009; Andersen, 2010; Yates, 2014; Gschwandtner, 2016; Lieser et al., 2018; Bondie, 2020; Hersh, 2020). Preparation included items such as technology, presentation design, and defining the roles of the hosts. Presentation included elements of setting expectations, frequent checks for understanding, interaction, interest polls, and use of chat functions. Finally, post-webinar follow up embedded items including communication, additional resources, and use of polling or surveys (McBrien et al., 2009; Andersen, 2010; Yates, 2014; Gschwandtner, 2016; Lieser et al., 2018; Bondie, 2020; Hersh, 2020).

Preparation

The format and design of a webinar impacts engagement and retention (Yates, 2014). Knowing audience characteristics is critical when determining presentation materials, pacing, and activities (Andersen, 2010; Yates, 2014; Lieser et al., 2018; Fontichiaro et al., 2021). Andersen (2010) emphasized the value of investing substantial time in developing good presentation materials as a foundation for a successful webinar. In effective webinars developers to design the session with participants in mind (Lieser et al., 2018; Fontichiaro et al., 2021). Yates (2014) found high-quality sessions supported sustained attention and engagement was dependent on the relevance. Using theories of competency-based learning and the 4 Es learning cycle (i.e., engagement, exploration, explanation, and extension), Lieser et al. (2018), developed a framework of tools that promote active learning. The proper platform can support the use of webinar tools and aid in the success of the presentation (Frederick, 2011).

Ease of technology supports presenter and participant motivation and engagement (Yates, 2014). McBrien et al. (2009) and Yates (2014) reported if participants experience technical difficulties, the effect of the presentation is weakened. Research suggests hosts and presenters know how to use the features available for the selected platform and be able to troubleshoot or use IT support before and during the presentation (Frederick, 2011; Gschwandtner, 2016; Lieser et al., 2018). Andersen (2010) supported arriving at the webinar early enough to go through a dry run to head off issues with slide sharing, polls, and sound.

Collaborative webinars include teams of hosts who share in completing the task of behind-the-scenes preparation. Defining the roles of each member supports smooth execution of the webinar session (Andersen, 2010). Teams should consider who will communicate with participants prior to the session, who will keep track of attendance, who will be host/co-host, who will share the slides, who will let participants into the session, who will introduce the speaker, who will be the moderator, and who will monitor the chat. Answering questions like these, in advance, gives team members clear direction and eliminates confusion and delays during the session. Practicing or performing a dry run of the presentation allows teams to predict and troubleshoot issues that may arise during the webinar. Teams meet with the presenter to check links and video sound, ensure screen sharing and polls are working, and preview the entire presentation by walking through the agenda (Andersen, 2010; Fontichiaro et al., 2021). Purposeful planning and preparation allow participants to actively engage in a variety of learning modalities. Setting the agenda for these activities allows forward progression of the presentation and ensures the learning outcomes are met within the designated time frame.

Presentation

After welcoming the participants to the session, facilitators should allow time to take care of typical housekeeping matters, set clear expectations that will support participants’ understanding of how they can ask questions, respond using emoticons, participate in polls, mute/unmute, and use the chat feature (Andersen, 2010). Webinars function to develop the professional capacity of participants (Fontichiaro et al., 2021). Facilitators should make participants aware of the learning objectives as well as, provide information on the session takeaways, the practical applications, and the extension opportunities (Aguilar and Cohen, 2022). Establishing the schedule and previewing activities will provide attendees with a roadmap for the session. The intentionality of the time that will be spent on each agenda item allows the moderator the discretion of structured flexibility (Fontichiaro et al., 2021; Aguilar and Cohen, 2022). Advanced practice of the agenda allows the presenter to predict when and how they will check for understanding and address questions posed in the chat.

Checking in with participants throughout the session is key to monitoring understanding and engagement. There are features built into many platforms that allow participants to post comments and questions in a chat box or respond to polls. These features can also be used to support active engagement and drive instruction (McBrien et al., 2009; Gschwandtner, 2016; Lieser et al., 2018; Hersh, 2020; Fontichiaro et al., 2021; Aguilar and Cohen, 2022). McBrien et al. (2009) found the chat option increased student involvement, reduced anxiety, and provided a space for shy participants to express opinions. In the same research, it was noted that polls allowed for everyone to see how others felt (McBrien et al., 2009). Virtual learning platforms limit participant-to-participant interaction (Yates, 2014). Chats or backchannel communication features, polls, and breakout room sessions mitigate the perceived distance of virtual learning (McBrien et al., 2009; Gschwandtner, 2016; Lieser et al., 2018; Aguilar and Cohen, 2022).

Effective webinars include time for participants to interact with one another (McBrien et al., 2009; Gschwandtner, 2016; Lieser et al., 2018; Aguilar and Cohen, 2022). Facilitation of breakout rooms supports active collaboration and allows time for information processing (McBrien et al., 2009; Lieser et al., 2018; Bondie, 2020; Hersh, 2020; Fontichiaro et al., 2021; Aguilar and Cohen, 2022). Structuring the breakout session allows participants to make the most of their time together and be prepared to share out when reentering the whole group session (Bondie, 2020; Hersh, 2020). To wrap up the session, facilitators are advised to take time to summarize, reflect, and gather feedback; remind participants of the learning objectives and how they were accomplished; highlight important thoughts, comments, and questions that were unique to the learning session; and gather immediate data that will inform future webinars (Bondie, 2020).

Post-webinar follow up

Follow up with participants after the webinar has concluded is recognized as best practice. Andersen (2010) recommends preparing a short email thanking them for their participation, reiterating the main points of the session, and providing them with any additional information mentioned during the session. Participants should be given a link that allows them to provide feedback. This can be accomplished through a survey (Guskey, 2002; Gschwandtner, 2016; Bondie, 2020; Hersh, 2020). Feedback allows the design team to make adjustments and tailor webinar offerings to the current needs of the audience.

Webinar series implementation

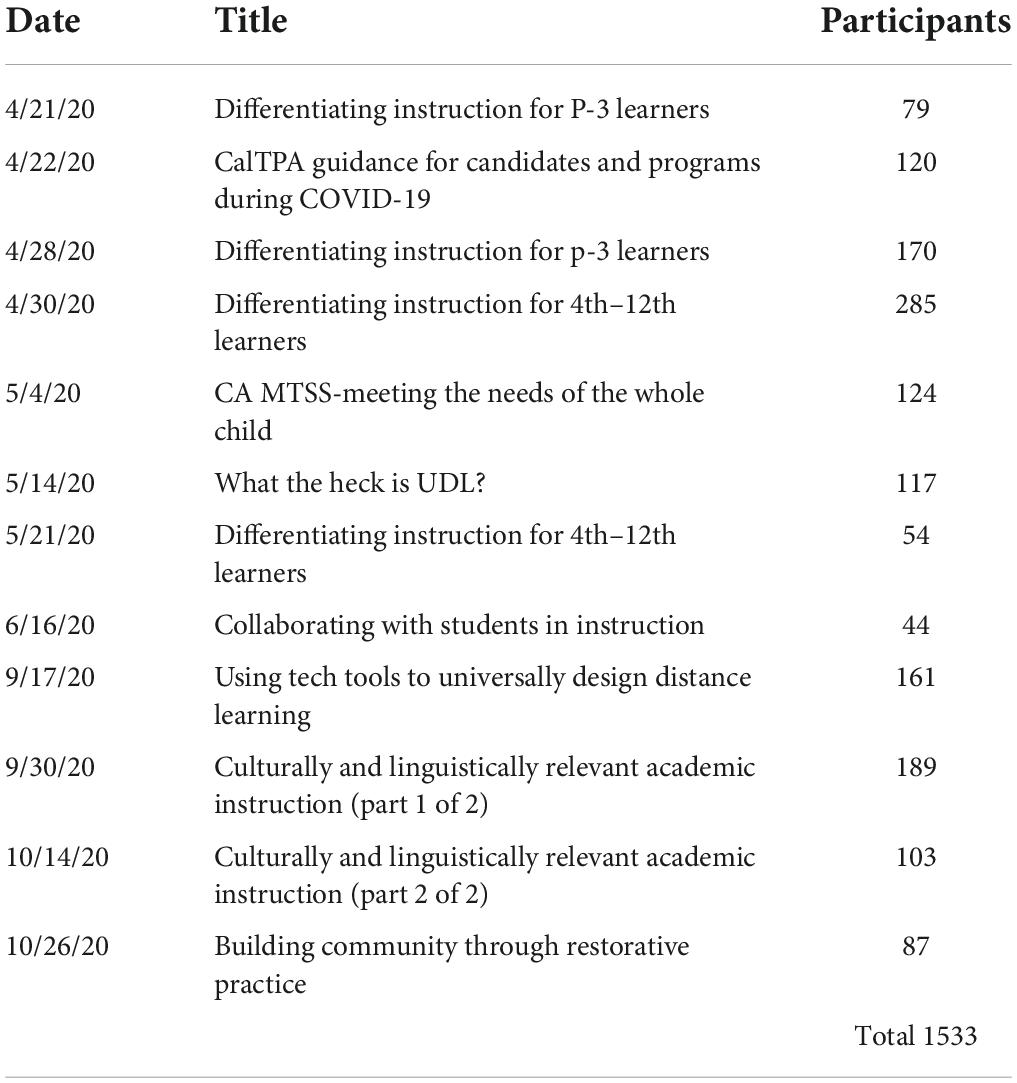

From April 2020 to November 2020, a team of education faculty designed and delivered 12 webinars on several topics associated with best practices and aligned with state credentialing requirements (see Table 1). The webinars were designed based on prior research and aimed at supporting preservice educators as they worked to complete their clinical hour requirements. Webinars were also made available to educator preparation program faculty, mentor teachers, and university supervisors. The webinar design team used available research and embedded best practices for virtual learning environments to support retention, engagement, and collaboration. Pre-Webinar planning responsibilities were divided, with one team member assigned to be the liaison between the team and the presenter; this team member was also responsible for developing the Padlet. One member was responsible for registration and communication with the registrants. One member was assigned as the session moderator. All members of the design team met regularly to check-in and collaborate. Webinars were structured to be one to two hours in length. Some webinars included breakout rooms, and others included whole group engagement with opportunities for questions and answers. Backchannel chats and interest polls were used to guide discussions. All webinars included a Padlet with extension activities that aligned with CCTC requirements for clinical hours. Each webinar was followed up with an email to participants that included an appreciation note, a link to the survey and Padlet, and information about upcoming learning opportunities.

The purpose of this study was to address the following research questions: (a) How, if at all, did participants perceive the webinars and extension activities impact their understanding of and ability to apply content and strategies introduced in the webinars? (b) How did candidates perceive the usefulness of the webinars and extension activities in obtaining clinical hours? and (c) How do participants perceive the remote learning practices used in the delivery of the webinars?

Materials and methods

This study was based on standard survey design (Creswell and Creswell, 2018) using descriptive analysis of a survey with five-point Likert scale questions and an option for comments. We focused on this specific design to make sense of the data and make decisions about professional learning opportunities and formats for the 2020–2021 academic year, in which many preservice and in-service teachers would be engaging in remote professional learning. To establish face validity of the instrument, the instrument was reviewed by five experts in the field of preservice and in-service teacher learning and research. Adjustments were made to wording and items based on feedback. The overall survey design included three parts and was constructed with the intention to focus on demographic information (Section “Background”), impact of webinars on learning and practice (Section “Webinar series implementation”), and impact on attainment of clinical hours as well as recommendations for future webinars (Section “Materials and methods”). The survey was kept general and was used across all webinars regardless of topic area (see Appendix for survey questions).

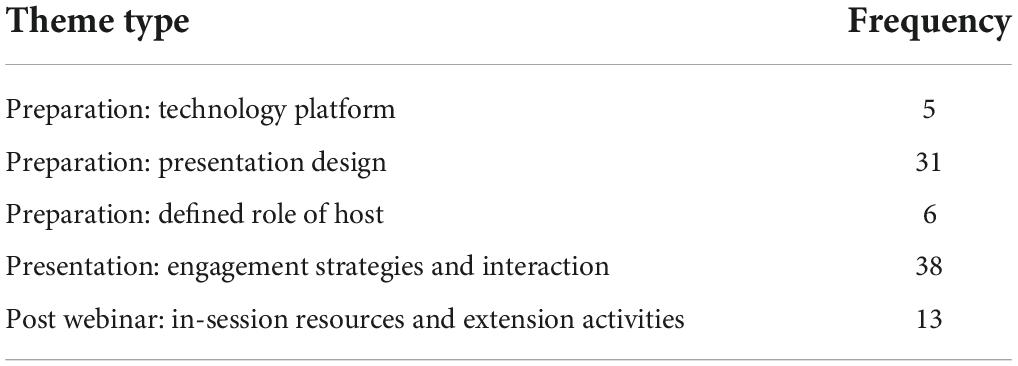

In regard to Research Question 3, the survey did not ask questions specifically related to the webinar format. Rather, we sought to explore whether participants naturally comment on these features in the context of responses to the other questions on the survey. Thus, we developed an a priori coding scheme (Saldaña, 2013) with codes that relate directly to the three main components of webinar development and associated subcomponents introduced in the manuscript (i.e., preparation, presentation, and post-webinar follow up; McBrien et al., 2009; Andersen, 2010; Yates, 2014; Gschwandtner, 2016; Lieser et al., 2018; Bondie, 2020; Hersh, 2020).

Participants

Surveys were sent to 1,533 individuals across the state of California who logged on to engage in one or more of the webinars. Participants represented 219 school districts, 35 counties across the state, and 55 institutions of higher education. The response rate of teacher candidates for the post–session survey was approximately 16%, yielding 248 responses. The Active Education Webinar Series drew the attention of candidates across multiple credential types (see Table 2). Multiple subject (MS; i.e., elementary licensure) candidates account for 43.48% of the preservice teacher demographic profile, single subject (SS; i.e., middle or high school licensure) candidates represented 27.8%, and special education (ES; i.e., education specialists mild/moderate and moderate/severe—special education credential options in California) candidates combined to represented 12.9%. The two additional categories were bilingual and “other.” Bilingual educators represented 0.02% of the population. The “other” category, which represented 12.9% of the participant population included primarily early childhood educators and educators with multiple credentials (e.g., multiple subject and educational specialist dual credential). See Table 2 for complete information.

Data sources

Survey data were collected following each webinar via an email invitation sent to all webinar participants, with a second follow up invitation sent a week later. Twenty-three questions were included in the survey. The first three items were demographic in nature and reported out in the participant’s section. There were seven likert-scale items with options for expanded comments for each item. One additional item requested information related to additional learning, take-a-ways, or recommendations. Comments were reviewed and coded in direct relation to specific items, research questions, and the remote learning format used. Only participants who responded to every question on the survey are included.

Results

The overarching research questions included: (a) How, if at all, did participants perceive the webinars and extension activities impact their understanding of and ability to apply content and strategies introduced in the webinars? (b) How did candidates perceive the usefulness of the webinars and extension activities in obtaining clinical hours?, and (c) How do participants perceive the remote learning practices used in the delivery of the webinars? We report the results of the Likert portion of the survey and then report comments to provide context for responses. A detailed description of the analysis can be found in Table 2.

Participant perceptions of impact

In regard to perceptions of impact, participants were asked to indicate whether the introduced content increased or reinforced their understanding, whether they felt more prepared to apply the content, and whether they felt more prepared to develop content and deliver lessons that engage students and families. When responding to “My understanding of the content introduced in the webinar has increased or been enforced,” 96.3% (n = 239) of participants strongly agreed or agreed with this statement. There was little difference across credential areas, with 93.3% (n = 105) of MS preservice teachers indicating strongly agree or agree, 94.7% (n = 66) of SS preservice teachers indicating strongly agree or agree, and 91.3% (n = 30) of ES indicating strongly agree or agree. Participants representing the bilingual credential (n = 6) and other category (n = 32) responded with 100% strongly agree or agree. Overall, much smaller percentages were noted for neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree, with an average of 3% (n = 9) of participants choosing those options, ranging from 0.9 to 4.3% for MS, SS, and ES.

Similar to the understanding of content, all participants felt prepared to apply content and develop and deliver lessons. When responding to “My ability to apply content has been increased or reinforced,” approximately 95% (n = 237) of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that their ability to apply the content introduced in the webinar had increased or been reinforced. For specific subgroups, 93.6% (n = 102) of MS preservice teachers and 95.6% (n = 66) of SS preservice teachers indicated strongly agree or agree. Similarly, 96.9% (n = 31) of ES indicated strongly agree or agree. Moreover, 100% of participants with the bilingual credential (n = 6) and in the other category (n = 32) responded with agree or strongly agree. In addition, when asked if they felt better prepared to develop content and deliver lessons around the topic areas, approximately 92.4% (n = 232) of the entire population indicated they strongly agree or agree. For specific subgroups, 93.4% (n = 104) of MS preservice teachers indicated strongly agree or agree, 87% (n = 60) of SS preservice teachers indicated strongly agree or agree, and 96.9% (n = 31) of ES indicated strongly agree or agree. In addition, 83.35% (n = 5) of bilingual credential and 100% of other participants (n = 32) indicated strongly agree or agree. Responses for neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree were chosen by 6.4% (n = 16) of participants, ranging from 0.9 to 16.7% for MS, SS, ES, and bilingual. Although there are slight differences in percentage across credential areas, these were minor. Responses for reaching diverse learners were similar, with about 95% of participants indicating strongly agree or agree, with little variability across credential areas. Complete results can be found in Table 2.

Participants were also asked about their intention to use webinar hours and experiences toward their credential and if they would use and apply this information in collaboration with a faculty member, university supervisor, or mentor teacher. Across all credential areas, 86.2% (n = 94) of participants indicated that they planned to use hours and associated webinar activities toward their credential requirements in some way. The remaining 13.8% of participants indicated that the webinars were not being applied to credential requirements. Similarly, approximately 86% of survey respondents agreed they planned to use those tools in collaboration with their university supervisor, mentor teacher, or other expert educator to continue accruing hours toward their credential, with the remaining 14% suggesting that they would not be using the materials in collaboration with others.

Participants’ comments supported the survey results. Participants indicated the content was meaningful and helped them further understand or reinforced content, particularly related to differentiating instruction, UDL, and culturally and linguistically responsive teaching. Comments were specifically related to the tools that supported application of content such as the organizers and workbooks provided during the session. For example, comments related to differentiating instruction included one participant who mentioned, “The six step outline provided in our handbooks will be a very useful tool for me in the future,” and another participant indicated, “The organizer for correcting mismatches was extremely helpful. It was clear and useful.” Furthermore, in regard to UDL, participants noted, “Great activities to reinforce my understanding of UDL” and “Thank you for showing how to implement UDL when lesson planning and giving examples.” These comments overall suggest the “hands-on” nature of the webinar supports the high responses indicated in the Likert scale questions. Participant comments related to culturally and linguistically responsive teaching included, “Creating culturally diverse instruction can be difficult but I think the resources that were provided is a start and can [be] included in my toolbox.”

In addition to comments supporting the practices, we acknowledge the comments that may support the neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree responses. These responses were related to needing more “real-world” examples, more examples related to specific content areas (e.g., mathematics) and more time to apply the concepts and not rushing through the content. These comments support the Likert scale responses in that some participants did note needs for changes to the webinars for them to successfully encourage content knowledge and practical application.

Comments related to the use of Padlets which included extension activities that could be used with a mentor or supervisor suggest although many participants found the webinars and extension activities helpful in completing credential requirements, others were unsure and still did not know what their educator preparation program’s policy would be. Although some participant comments indicated use toward completion (e.g., “I am happy that I could use this to help me complete requirements, so thank you”), others indicated they were participating more for personal development or enrichment. For example, out of the 12 participants who commented on this section, eight participants indicated they did not need this for any credential requirements and were engaging in the webinars for professional or personal development. Thus, it is unclear how applicable these experiences were toward completing clinical hour requirements.

Best practices for webinar development and delivery

A number of comments directly related to the virtual learning environment and practices. These included preparation, presentation, and post-webinar follow up elements. Preparation components highlighted in the comments included the virtual platform, the presentation design, and the preparedness of the host(s). Presentation elements included reference to interaction opportunities, and, for post-webinar follow up, participants mentioned the additional resources provided via the Padlets. Table 3 represents the frequency of themes.

Preparation

Overall, participants were appreciative of the selected platform and the flexibility it gave to include audience participation. Breakout rooms, whole group discussions, polls, and chat features were highlighted as being engaging and supported relevancy. Presenter preparation was also noted throughout the comments. The slide deck design, organization, and content were emphasized and appreciated. Pacing and the integration of activities were also mentioned and given praise. The support provided by all members of the webinar team was acknowledged in the chat forum.

Technology platform

Comments supporting the selected platform included general thoughts about the features available to the audience throughout the session(s). A total of nine comments included reference to the technology platform. For example, one participant wrote, “Thank you [for] doing this webinar—well thought out. esp[especially] with multiple ways to engage (poll, chat etc.).” Another participant mentioned the platform and features stating, “The presenters were engaging together, followed the material closely without giving away too much, and incorporated Zoom features well (poll and chat). Pacing was perfect.” A third comment encouraged the facilitators in the continued use of the platform features by stating, “Lots of opportunities to engage in chat box, polls, workbook. Very nicely done!” A final comment praised the facilitation of interaction in the virtual setting: “Love the interaction despite being virtual.”

The use of discussions, breakout rooms, and the chat feature were repeated throughout the comments including both praise and request for more time spent engaging in these activities. For example, one participant wrote, “I thought the discussions and the chats were very insightful. It helps to have other people ask questions that you haven’t thought of.” Another participant commented, “There were some great ideas added by participants, unfortunately I was unable to copy them all down.” Another example was demonstrated in the following comments: “Loved thr[e] large group to small group activity,” and “I would have enjoyed more time in the breakout session, I felt we were rushed through that portion.”

Presentation design

Comments referencing presentation design occurred 31 times. Participants were complimentary of the presentations and time spent by the presenter designing the slides, activities, and supporting materials. In general, it was noted how the presenters, through their design, structure, and organization, connected with and engaged the audience. Comments related to the design included “Great visuals” and “Nice Graphics and practical experience using student profile[s] with strategies.”

Some remarks associated with the structure and organization of the slides included “The information was helpful, clear, and concise;” “Superb! Great flow, pace, clear, and easy to understand;” “Well-organized workshop;” “Amazing job! Very well-organized presentation, and well-rehearsed;” “Thank you for the opportunity to learn from an extremely thought out and organized distance learning experience;” and “One of the best webinars I’ve attended. It was very well-prepared and information was strongly supported. Breakout rooms with a presenter elevated the material. Thank you!”

Participants appreciated the materials, examples, and step-by-step instruction provided by presenters. Indicators that participants were engaged and able to make connections with the presenter and the content were seen in comments such as:

• “I’ve taken a course about UDL, but I heard analogies that will stick like the professional bowler’s tip to curve and aim for the most difficult pins, then the others will fall in a domino effect. Loved that!”

• “Thank you for showing how to implement UDL when lesson planning and giving examples.”

• “The presenters were very informative and engaging,” and “You broke down the steps of resolving conflicts between an environment and a child in understandable and very manageable pieces. Thank you.”

• “The presenters laid out the steps in planning for diverse learners in a very practical way with steps that can easily be implemented in my classroom.”

Defined roles of host(s)

The collaborative efforts of the webinar team were not overshadowed by the presenters’ performance, and the defined role of the host was referenced six times. Several comments were made related to the “behind the scenes” support provided including “The presenters were awesome. The person answering questions on the chat deserves to be recognized also. She was very helpful!” A participant further commented:

Presenters were engaging and presented like a “talk show/podcast” instead of just lecturing which was nice, they engaged us through quizzes, provided real example students which were helpful, enjoyed hearing their touching story, gave us good material to follow along (workbook), [the presenter] was proactive in answering questions and posting info in the chat regularly.

The team also stepped in and supported as needed throughout the presentations and during the breakout sessions. This was noted in positive comments such as “I loved how some of the facilitators shared their personal experiences—off scripts moments humanize this experience and make it more tangible to incoming educators;” and “We did not all agree on what the talking points were, and that created an awkward moment, but once our leader logged on, it was cleared up.”

Presentation

Though preparation served as a key to success and supported the positive response given on the Likert scale questions and comments, execution of the presentation was equally critical. Noted throughout the comments was the presenters’ pacing and use of engagement strategies, which included frequent checks for understanding via chats, polls, and large group activities and time allocated for questions. Additionally, structured interaction in small group breakout rooms was an undeniable activity participants valued. Comments from the survey supported the use of these approaches over a lecture style presentation. It was noted that webinar(s) felt like workshops where knowledge and experience could be applied to the topic(s).

Engagement strategies and interaction

Comments supporting the usefulness of engagement activities to deepen learning occurred a total of 38 times and included statements such as “Great activities to reinforce my understanding of differentiated instruction,” and “I appreciated how they incorporated us into the webinar and had me doing some critical thinking early in the morning.” Another participant stated, “This Webinar was an amazing presentation/workshop. The activities really helped me deepen my understanding of UDL and the 6 steps.” Moreover, one participant mentioned the meaningful discussions and interactive chats: “I thought the discussions and chats were insightful. It helps to have other people ask questions that you haven’t thought of.”

In addition to general engagement and whole group activities, participants specifically mentioned the presentation style of movement from large group to small group. This desire to interact with colleagues and peers was reported through the comments including statements such as “Love the interaction despite being virtual;” “I especially enjoy the polls and breakout sessions;” “It was nice to hear what others had to say about their experiences;” “Good opportunity to chat with other folks. But not a lot of time to engage with everyone;” and “The breakout rooms were great. I learned from other teacher[s] what is working at their school and what is not.”

Post webinar

Best practices for post-webinar engagement include communication, additional resources, and surveys. Participants, who referenced this 13 times, primarily commented on the resources provided during the webinar and the usefulness of the Padlet extension activities. Comments supported both the effectiveness of engaging with the resources during the webinar to familiarize themselves with the tool and the appreciation that additional materials and activities were curated for future exploration.

In-session resources and extension activities

Checklists, step-by-step instructions, and organizers were most appreciated by the participants. One participant commented on the support felt during the session stating, “Very comprehensive and tones [tons] of support documentation/resources.” Several other participants appreciated the tangible takeaways commenting, “The checklists will help immensely;” “The six-step outline provided in our handbooks will be a very useful tool for me in the future;” and “The organizer for correcting mismatches was extremely helpful. It was clear and useful.”

The curation of resources into a Padlet for each webinar was recognized as an invaluable feature of the webinar series. One participant commented on the career-long application of the tool by stating, “I plan to use the Padlet tools for as long as I am a teacher.” Another appreciated the potential collaboration opportunities the resources provided: “They provided awesome resources that I hope to be able to use with my colleagues in the future.” Many others commented on the practicality of the prepared resource(s): “I appreciate all the information and resources and further reading included in the webinar;” “This has provided a list of distant learning tools for the various UDL categories;” and “Creating culturally diverse instruction can be difficult but I think the resources that were provided is a start and can [be] included in my toolbox.”

Discussion

One of the goals for the statewide webinar series was that teacher candidates would build and apply their knowledge of topics included in California’s Universal Teaching Performance Expectation. Even with in-person instruction and service hours temporarily unavailable, teacher candidates and mentor teachers needed to build their knowledge. Schools and organizations had to consider evidence-based instructional practices for teacher candidate development and other professional development opportunities and how to translate formerly in-person supports and opportunities online.

Use of best practices in webinar development and delivery

A primary focus of these webinars was to prepare teacher candidates to take the California Teaching Performance Assessment. This assessment is a critical component for teachers who are working to earn their certification. By targeting teacher candidates and including evidence-based virtual learning instructional strategies with a specific focus on inclusive practices we supported a key population in building knowledge, skills, and abilities that are essential in establishing and scaling up inclusive practices.

The active webinars were highly successful at meeting the goal of supporting preservice teachers build and apply knowledge. The majority of participants were teacher candidates who needed hours and experience to earn their teaching certifications and prepare for the certification exam. Participants reported strongly positive responses to the active webinar series presenters, content, process, and materials. This is consistent with prior research that suggests that format and design of webinars have a direct relationship with engagement (Yates, 2014). Furthermore, the results of this study suggest the notion that successful professional learning is directed toward specific participant population needs (Lieser et al., 2018; Fontichiaro et al., 2021; Aguilar and Cohen, 2022). In reference to the first goal of building and applying knowledge of topics included in California’s Universal Teaching Performance Expectations participants reported the material and processes from the Teacher Candidate webinar helped them reinforce or increase their understanding of the material. Developing the webinars in alignment with the specific populations needs such as meeting the criteria related to earning their specific credential may have attributed to the high levels of participant satisfaction.

Checklists, organizers, handbooks, and step-by-step instructions were built into each webinar to allow for guided practice and application. Andersen (2010) and Aguilar and Cohen’s (2022) research supports this approach to engaging material development suggesting that materials are an essential foundation of a successful webinar. One added feature of the webinar series was the development of and access to the extension activities, which provided participants with opportunities for continued engagement and practice with the content. These activities were intended to provide a platform for candidates and mentors to continue the conversation beyond the webinar. This engagement is consistent with prior research that shows active collaboration and engagement are critical to the structure and format of a webinar (McBrien et al., 2009; Bondie, 2020).

There were slight differences between multiple subject (elementary) and single subject (middle and high school) credential areas, with single subject participants showing slightly less agreement with the utility and application of the webinar content. Educators who focus on a single subject matter may need differentiated content that meets their specific needs. In the future, we may want to customize specific subject matter content. This may make the webinars more meaningful and applicable across all credential areas.

Based on this research, future webinars must include intentional formatting and design of materials aligned with virtual learning techniques, interactive tools for during-session engagement, and post-webinar follow ups. Considerations for formatting and design should include ease of use within the selected platform, access to links for presentation slides, materials, and additional resources, and careful planning of the agenda to balance content delivery, engagement activities, and checks for understanding. Interactive tools should support content processing, encourage formative feedback to support future session segments, and allow participant-to-participant interactions. Finally, post-session is recommended to allow for additional participant input and links to presentation materials.

Focus on inclusive practices

Across all webinars participants agreed the information they learned would support their ability to meet the needs of a wide range of students, including students with disabilities, students from different socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds, and students of different races. New teachers feel better prepared when they have learned strategies for increasing access for all student (Crispel and Kasperski, 2019). Proper supports and services can be critical to the success of students with disabilities in all classrooms (Thompson et al., 2018). Teacher candidates indicated feeling prepared to create content, lesson plans, learning experiences, or support structures for students and families after participating in the webinar. Preparation is also critical to new teacher success and retention (Guha et al., 2017).

Implications for post COVID-19

The pandemic launched the education community into online and virtual teaching. This created some chaos but also opportunities for creativity and innovation. Educators across the state participated in learning and collaboration. The webinar series established the possibility of quality online professional development that is not limited to local communities. Opportunities for teacher candidates and new teachers to join a virtual learning community can create connections with colleagues and support systems across geographic areas. This research adds to a growing body of evidence that supports engaging learning opportunities in virtual settings for teacher candidates and new teachers. Access to virtual professional learning was widely considered highly beneficial suggesting the need to focus on continued virtual professional learning for teacher candidates and new teachers.

Limitations

Despite this research providing practical and actionable results related to addressing teacher candidate competencies during times of disruption to “typical” in-person learning and student teaching, we acknowledge the limitations of this study. As this study was done in collaboration with a number of organizations, our team did not collect demographic data related to race, age, or gender that may have further informed the results or implications. Moreover, we recognize the 16% response rate may enhance the need to exercise caution when generalizing results to all webinar participants. Future research will include follow up interviews to triangulate data should a response rate be higher to strengthen the results of the study.

Conclusion

Many educator preparation programs and education organizations rose to the challenge of providing webinars as an emergency response to the impact COVID-19 had on teacher credential programs. The education system was not prepared for the disastrous effects of a pandemic and scrambled to initiate online learning. Results suggest access to small group learning for teacher candidates led by an expert facilitator was perceived as an effective way to continue mentorship and development of skills in a virtual environment. Furthermore, access to extension activities such as lesson planning materials and videos aligned with each webinar was well-received. Candidates found this helpful in continuing to apply and understand the concepts and strategies. Candidate suggestions demonstrate a need for continued professional learning communities or communities of practice that provide teacher candidates additional support and mentorship.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Chapman University, Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SM lead the data analysis, literature review, main manuscript preparation, and lead the copy editing of the final manuscript. MC co-lead the development of the webinars, development of data collection instruments, data collection, and lead the methods development. AS co-lead the development of the webinars, development of data collection instruments, data collection, and supported the overall manuscript development and revisions. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded with support from the Thompson Family Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aguilar, E., and Cohen, L. (2022). The Pd Book: 7 Habits That Transform Professional Development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley Jand Sons, Inc.

Andersen, M. H. (2010). Tips for effective webinars. New York, NY: ELearn Magazine, 1–10. doi: 10.1145/1693041.1710034

Bondie, R. (2020). Practical tips for teaching online small-group discussions. ACSD Express 15. Available online at: https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/practical-tips-for-teaching-online-small-group-discussions

California Commission on Teacher Credentialing [CCTC] (2016). California Teaching Performance Expectations. Sacramento, CA: California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. Available online at: https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/standards/adopted-tpes-2016.pdf (accessed March 20, 2020).

California Commission on Teacher Credentialing [CCTC] (2020). Guidance for Field Experience in Educator Preparation Programs on COVID-19. Available online at: https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/commission/files/covid-19-clinical-practice-field-experience.pdf (accessed March 20, 2020)

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Crispel, O., and Kasperski, R. (2019). The impact of teacher training in special education on the implementation of inclusion in mainstream classrooms. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 25, 1079–1090. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1600590

Fontichiaro, K., Yankson, K., Stanzler, J., and Kolb, L. (2021). Create PD Webinars that Engage Educators. ISTE. Available online at: https://www.iste.org/explore/professional-development/create-pd-webinars-engage-educators (accessed August 5, 2022).

Frederick, K. (2011). Weaving your virtual seminar: Create a webinar. Schl Library Monthly 27, 39–41.

Gschwandtner, M. (2016). Use of webinars for information skills training: Evaluation of a one-year project at Canterbury Christ Church University. Sconul Focus 66, 56–61.

Guha, R., Hyler, M., and Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). The teacher residency. a practical path to recruitment and retention. Am. Educ. 41, 31–34. doi: 10.1177/0031721717708292

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Does it make a difference? Evaluating professional development. Educ. Leadersh. 59, 45–51.

Hersh, S. (2020). Yes, Your Zoom Teaching can be First Rate. Inside Higher Ed. Available online at: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/07/08/faculty-member-and-former-ad-executive-offers-six-steps-improving-teaching-zoom (accessed July 8, 2020).

Lieser, P., Taff, S. D., and Murphy-Hagan, A. (2018). The webinar integration tool: A framework for promoting active learning in blended environments. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2018:7. doi: 10.5334/jime.453

McBrien, J. L., Cheng, R., and Jones, P. (2009). Virtual spaces: Employing a synchronous online classroom to facilitate student engagement in online learning. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distributed Learn. 10, 1–17. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v10i3.605

Saldaña, J. (2013). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers + Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Thompson, J., Walker, V., Shogren, K., and Wehmeyer, M. (2018). Expanding inclusive educational opportunities for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities through personalized supports. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 56, 396–411. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-56.6.396

Yates, J. (2014). Synchronous online CPD: Empirical support for the value of webinars in career settings. Br. J. Guidance Couns. 42, 245–260. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2014.880829

Appendix

Active education webinar series survey

Each question used a Likert scale of five response options that included: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree. Participants also had the opportunity to elaborate on each item by completing an open-ended comment box.

Q1. My understanding of the content introduced in the webinar has increased or been enforced.

Q2. My ability to apply the content introduced in the webinar has increased or been reinforced.

Q3. I feel more prepared to create content, lesson plans, learning experiences, or support structures for students and families after participating in the webinar.

Q4. The information I learned and practiced today will help me in my clinical practice and future teaching to meet the needs of diverse learners.

Q5. The webinar helped me in completing the hour and TPE requirements for my teaching credential.

Q6. I plan to use the tool(s) presented in the webinar in collaboration with my university supervisor, mentor teacher, or other expert educator to continue accruing hours toward my credential.

Q7. I plan to use the extension activities provided on the Padlet in collaboration with my university supervisor, mentor teacher, or other expert educator to continue accruing hours toward my credential.

Keywords: COVID-19, virtual professional learning, preservice education, educator preparation, teacher preparation

Citation: Cosier M, Morgan S and Sandoval Gomez A (2022) High-yield webinar engagement strategies and teacher candidate professional learning. Front. Educ. 7:961043. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.961043

Received: 03 June 2022; Accepted: 16 August 2022;

Published: 23 September 2022.

Edited by:

Dominik E. Froehlich, University of Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Zeha Yakar, Pamukkale University, TurkeyPatricia Danyluk, University of Calgary, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Cosier, Morgan and Sandoval Gomez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Meghan Cosier, cosier@chapman.edu

Meghan Cosier

Meghan Cosier Sara Morgan

Sara Morgan Audri Sandoval Gomez

Audri Sandoval Gomez