The COVID-19 Pandemic and Outbreak Inequality: Mainstream Reporting of Singapore's Migrant Workers in the Margins

- Chua Thian Poh Community Leadership Center, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Singapore saw a majority of COVID-19 infections plaguing low-skilled migrant construction workers by late April 2020. In the initial phases of the outbreak, mainstream frames were quick to highlight the gathering of low-skilled workers in open areas as sites to be surveilled, shaping the divisive practices of othering in early frames on migrant worker behaviors. These reports were manufactured as Singaporeans continued to gather in public spaces in large groups during the outbreak. Mainstream reports were quick to inform audiences of the surveillance and control on display for disciplining migrant workers. As the crisis developed to impact migrant workers predominantly, the erasures are recovered with mainstream press reporting worker vulnerabilities and discussing the structural implications of managing migrant labor as neoliberal subjects. The structural conditions of migrant labor were, in fact, centered in mainstream narratives, and dormitories as public health threats were extensively discussed, shedding light on discourses relating to outbreak inequality. The rights framework, however, remained largely absent in mainstream news frames about migrant workers.

Introduction

The media is a crucial source of information about migrants and migration, influencing how they are portrayed and constructed. Studying the mainstream media for representing or limiting the enactment of subaltern agency informs us the role of the media in shaping migrant narratives. According to Bleich et al. (2015), the media creates openings for migrants and minorities to engage in the public sphere that allows them to bring forward their representations, interests, and identities. This paper interrogates how the mainstream media shaped frames about low-wage migrant workers and the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore.

In Singapore, despite the early onset and governance of the COVID-19 outbreak in January 2020, the nation-state came under significant scrutiny by international media for outbreak inequality among its migrant construction worker (MCW) community. By May 2020, MCWs made up 90% of infections in the country (Ng and Ong, 2020; Yea, 2020). In discussing the context of migrant workers and the COVID-19 infections in Singapore, Dutta (2020a) critiques the pernicious use of neoliberal techniques in the control and management of low-wage migrant workers. He argues that these techniques of labor management led to the rapid and exponential infections among this vulnerable group of workers.

Defined as extreme neoliberalism, the authoritarian management and governmentality of low wage migrant workers in Singapore (control, surveillance, and management) exacerbated infection rates within these community of workers (Dutta, 2020a). Through the adoption of neoliberal governmentality, the various stakeholders extract from the subaltern body maximum economic benefits, with limited freedoms to organize and activate for themselves. These techniques of management include policy frameworks that govern low-waged migrant workers (MCWs and MDWs). Regulations tied to work permits that bind them to a single sponsor (Parreñas et al., 2020), silencing dissidence from workers that protest these conditions, and disciplining their labor through strict controls via work permit terms, tight visa restrictions, and health surveillance (disease screening) are examples (Bal, 2015; Dutta and Kaur-Gill, 2018; Kaur-Gill and Dutta, 2020). Dutta (2020a) argues that this model of governmentality is exported to Asia as a gateway for transnational capital. The poor housing standards (cramped, unhygienic, unsanitary) such as dormitories (Hamid and Tutt, 2019; Dutta, 2020b) and the absence of a labor rights frameworks to protect migrant workers from exploitative conditions are other ways we see the techniques of neoliberalism exercised in the management of low-wage migrant workers in Singapore. Such neoliberal techniques of management create the rife opportunity for precarities and im(mobilities) for low-wage temporary migrant workers working in the city-state (Dutta and Kaur-Gill, 2018). These neoliberal tailored strategies of labor-management leave vulnerable workers to several exploitative conditions.

This paper, therefore, studies mainstream narratives in its discussion of migrants and their health during the COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore, theorizing the operating logics of the mainstream press in an authoritarian context of news production (George, 2007, 2012; Ortmann and Thompson, 2020). Wald (2008) positions the outbreak narrative during a pandemic as the curation of a myth by architectural scripts of science, in which journalistic stories impact and transform a new global order. Wald's (2008) points to the accumulation of contradictions that begin appearing in an outbreak, “…obsolescence and tenacity of borders, the attraction and threat of strangers, and especially the destructive and formative power of contagion” (p. 33), where belonging and citizenship are weaponized. The weaponizing of belonging and citizenship during a crisis have health impacts for those that are typically othered in society, due to their vulnerable social positions.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Low-Wage Migrant Workers

Research during the COVID-19 pandemic caution how healthcare systems may remain neglectful of international migrant workers (Liem et al., 2020). For these workers, health services already remain difficult to access. Furthermore, pre-COVID-19 pandemic, international migrant workers already suffer a lower quality of health that is potentially further heightened during a pandemic (Liem et al., 2020). MCWs and MDWs make up ~9.9% of the population in Singapore. At 555,100 workers as of December 2019 (Ministry of Manpower, 2020), in a population of 5.6 million, low-skilled migrant workers make up a significant portion of Singapore society. The literature on migrant worker mobility continues to indicate jarring disparities faced by migrant workers during the migratory process (Dutta, 2017a; Yeoh et al., 2017; Hamid and Tutt, 2019).

In Singapore, MCWs are hired in large numbers to partake in what is known as 3(D) labor, dirty, dangerous, and difficult (Dutta, 2017b), mostly working in the construction sector (Kaur et al., 2016). MDWs, on the other hand, come from various parts of South East Asia and South Asia, migrating to participate in caregiving work within the confines of Singaporean households (Dutta et al., 2018). Both MCWs and MDWs partake in precarious work with restrictive conditions. Ordinarily, MCWs partake in long working hours, dangerous work, are at high risk to workplace fatality, and reside in poor living conditions that create serious health concerns for this migrant community (Dutta, 2017a,b). Rubdy and McKay (2013) describe,

their living conditions are invariably the most basic, as they are packed in overcrowded, squalid and unsafe premises that violate fire safety and land use laws, and that are located on the edge of the island's built up area, among derelict or industrial land, poorly served by public transport links (p. 160).

Living conditions of MCWs have been a site of extensive debate pre-COVID-19 crisis and further amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dutta (2017a) laid out a range of structural conditions tied to labor that remain precarious to migrant worker health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the structural conditions of migrant workers were amplified, with 90% of all infections in Singapore disproportionately afflicting the MCW community locally. Dutta's (2017a) findings “point toward how lived experiences with workplace safety are situated amidst the shifting contexts of work, attending to the overarching socio-cultural contexts of workplaces as well as spaces of everyday living” (p. 10). During the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore, MCWs bore the brunt of the infections in the city-state, leading to a spotlight on the inequitable living conditions FCWs inhabit in Singapore (Yeung and Yee, 2020).

In providing a framework to make sense of the rise in infections, Dutta (2020a) surveyed n = 100 surveys and n = 45 interviews with MCWs living in dormitories. The findings located that most workers described the structural barriers faced in containing the infectious disease spread. MCWs discussed accommodation standards concerning how it afflicted workers from practicing social distancing. The acquiring of sanitizer and soap remained challenging to access. Finally, fear and anxiety of depressed wages and the infectious disease spread were conveyed as mental health concerns. Lee et al. (2014) study on health information seeking behaviors among the migrant workers living in dormitories, indicated that while a majority of MCWs were accessing healthcare services, there were challenges with limited knowledge on insurance plans and delays in accessing health facilities when required. To add, a population of workers surveyed in the study highlighted that they would not seek treatment for serious health concerns. Harrigan et al. (2017) study on MCWs shared the relationship between migration and mental health in conversation with deportation threats made by employers when conducting construction work. These studies on MCW health make known to us the various ways health disparities are magnified for these communities of workers to the conditions of their labor. Baey and Yeoh (2018) further reinforce precarity and precariousness of migrant labor where a “growing vein of scholarship on migrant workers undertaking low paid, insecure and irregular jobs have shown how experiences of precariousness are inextricably linked to broader patterns of intensifying neoliberalism, labor market deregulation and the flexibilization of labor in post-industrialist societies” (p. 268).

For MDWs, unequal power relations such as living and working with their employers, create ambiguous and uncertain conditions for rest hours, privacy concerns, confinement and surveillance, mental health issues, food insecurity, and abuse (Dutta et al., 2018). Precarious and im(mobile) work conditions amplify health disparities for these workers. During the COVID-19 pandemic where Singapore rolled out its circuit breaker measures (Singapore's framing of a lockdown), NGOs such as the Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics (HOME) saw a 20% increase in distress calls from MDWs during the circuit breaker relating to being overworked, not receiving enough rest and the sustaining of verbal abuse (Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics, 2020).

Othering of Migrant Workers in Mainstream Discourse

Mainstream reports are often the early storytellers of an outbreak and fundamentally shape the outbreak narrative. When a pandemic threatens a global population, (Wald, 2008; Mason, 2012) the new fear of a floating population that moves as mobile migrants, passing mobile germs, fuels the media practices of boundary building of nation-states. In the context of globalized neoliberal economies, the racialization of the COVID-19 pandemic moves beyond just race alone, but interplays within the context of mobility and migration, where the movement of racial people as transnational citizens are centered in the discussion of epidemics (Briggs, 2003; Mason, 2015). With disparities in migration and mobility, pandemics become moments of governance of biosecurity threats by nation-states, rendering unequal health effects when the outbreak manifest (Briggs and Hallin, 2016; Sanford et al., 2016).

For example, Maunula's (2017) discourse analysis of the Canadian media on the H1N1 outbreak revealed, “expansion of “risk space” makes possible a particular kind of “pandemic subject” which operates as a neo-liberal bio-citizen” (p. ii), referring to risk space as the expansion of H1N1 spread by mobile citizens. In a study by Warren et al. (2010), media frames of the H1N1 pandemic reveal the role of the traveling body as a central actor in media discourse. Othering practices surfaced in discourses that centered the mobile person, where the frames of the “airport as a site for control and the ethics of the treatment of the traveler as a potential transmitter of disease” (Warren et al., 2010, p. 727). Dutta (2016) suggests that the militaristic global operation to contain the SARS virus amplified racist depictions of the Chinese cultural practices in health communication messages. Lee et al. (2005) inform how media portrayals of geographic borne spread contribute to the stigma of specific peoples in a way that is not proportionate to the risk as pandemics arouse stories of the omnipresent and its mysteries. Specifically, discussing the structural conditions of migrant labor in Singapore during the COVID-19 crisis, Dutta (2020a) argues that the “extreme neoliberal model of pandemic management” coupled with the authoritarian tools of disciplining and surveilling migrant labor, intensified the COVID-19 infections disproportionately for this marginalized population.

Not only are the structural conditions of labor for MCWs and MDWs impact health outcomes of workers, but migrant workers also remain erased from mainstream society by mainstream discourses. In discussing, public health and migrant workers, Grove and Zwi (2006), pay attention to how othering theory contributes to the subjugation of migrants in dominant discourse. The techniques of othering are meant to keep out subjects to not belong to the mainstream, naming the other, and mark the difference to oneself (Dervin, 2012). The creation of difference is aimed at stigmatizing the other as divergent and peculiar, “to reinforce notions of our own “normality,” and to set up the difference of others as a point of deviance” (Grove and Zwi, 2006, p. 1933). Grove and Zwi (2006) argue that the implications for othering migrants and reinforcing their marginal social position have downstream effects for public health. These include erasures of voice in mainstream discourses, where their stories remain unheard (Breen et al., 2006; Grove and Zwi, 2006). Tan's (2014) research on stereotypes in conversation with the integration of migrant workers in Singapore revealed that the mainstream press disseminated both positive and negative stereotypes of migrant workers. Negative stereotypes included “migrant workers as dangerous people” (p. 174) and “migrant workers as people with low integrity” (p. 174), threatening local livelihoods. Positive stereotypes circulated in the mainstream press suggested that migrants were necessary labor for the local economy.

Cheng's (2016) study of migrant workers in broad media entities in Taiwan often rendered workers as mere numerical entities, “…that treats this group as a faceless collective existing for the market need” (p. 2514). The absence of worker voices amplifies the degrading portrayal of migrant workers via the media through negative representations (Magpanthong and McDaniel, 2016; Mintarsih, 2019). Mintarsih (2019) suggested a lack of space for domestic workers both in their host and destination countries to form their narratives in dominant discursive spaces. The transience of migrant workers in state rhetoric contributed to how they are discursively constructed as the other in the media (Hamid, 2015; Kaur et al., 2016). Rubdy and McKay (2013) in studying language ideology and migrant work in Singapore suggests that the circulation of the nation as house metaphor,

lends logic to the portrayal of immigrants as “filth” that needs to be swept out for the house to be kept clean, strongly reminiscent of the colonial's derogatory references to the subaltern native as “dirty,” “filthy,” “degraded,” and “debased” (p. 165).

The social position of migrant workers in discourse and everyday lived experiences cannot be divorced from the poor structural conditions and health disparities faced by migrant workers.

Media Frames and Migrant Workers

Kaur et al. (2016) studied the role of the mainstream press in reporting the Little India Riot. It refers to a conflict that took place between MCWs in Singapore and the police on 8th December 2013, after a fatal bus accident killed a MCW. This led to a confrontation between workers and the police in the Little India area where MCWs congregate on their off days. The mainstream press centered voices of state actors in delivering a cultural explanation regarding the cause of the riot. Migrant worker voices remained predominantly absent in framing of the riot in dominant discourse, where voices of rioters were “violently silenced,” according to (Tan, 2016, p. 9) by mainstream narratives. The mainstream press re-circulated cultural tropes of South Asian FCWs that reinforced policies that sought to surveil, discipline, and re-arrange migrant worker bodies in various peripheral spaces across Singapore (Goh, 2019). Goh (2019) goes on to “argue that the 2013 riot by migrant workers accelerated the production of dormitory space to exclude migrant workers from access to the city and reproduce their physical needs” (p. 356). These dormitories become a dominant point of discussion during the COVID-19 outbreak concerning MCWs. Kaur et al. (2016) concluded that mainstream narratives “left absent in the frames were the alternative narratives grounded in the voices of the FCW (Foreign Construction Workers)” (p. 27).

Kaur-Gill et al. (2019) study on the media representations of MDWs revealed once again the absence of migrant worker voices in the mainstream press, “…voices of FDWs in the reporting of the news are often rendered absent, and when they are represented, they are often quoted to reinforce FDW policies set by the state” (p. 12). In discussing these representations located in The Straits Times, the dominant discursive space renders FDW voices peripheral, with civil society actors acting as proxies for FDW advocacy. While discussion on migrant labor and domestic workers were centered, the margins as sites for speaking remained erased. The othering of migrant workers in Singapore as outgroups are rooted in its post-colonial identity (Goh, 2008; Anderson, 2013; Dirksmeier, 2020). Bal (2017) discussed media representations of migrant workers as fraught, as victims, or as threats to Singapore society. The criminal representation of migrant workers surfaced throughout the 1990s (Bal, 2017), similar to Cheng's (2016) findings of migrant workers in Taiwan as represented through criminality. However, in Singapore, these representations were shifted when state voice actively dismissed these stereotypes due to the state's reliance on migrant workers to develop its local infrastructural economy (Bal, 2017).

Migrant worker rights in dominant discourse have been mostly absent. Goh et al. (2017) posit the limitations of a rights discourse in illiberal contexts, illiberal contexts referring to authoritarian governance that limit freedoms and coercively subdues dissent through institutional, state, and legal entities. According to Goh et al. (2017), the human rights discourse has limited appeal in changing state behavior toward the treatment of vulnerable migrants in places like Singapore. In studying the framing of the day-off campaign in Singapore by civil society actors, they purport the success of the campaign because it used a “cultural mediation strategy of vernacularization” (p. 89), where rights claims were framed in a manner that fit “with the institutional logics and cultural repertoire of Singapore society” (p. 89). However, (Goh et al., 2017) conclude that migrant workers must ultimately participate in advocacy about them, centering migrant voices in mediating for themselves. Where migrant worker voices were activated in advocacy efforts, the rights discourse framed the central tenets of advocacy (Dutta et al., 2018). Dutta and Kaur-Gill (2018) argue that without a rights framework in dominant mainstream discourse, the seductive lure of neoliberal practices will continue to locate itself in migrant labor management and governmentality.

The Press in Singapore

The press in Singapore broadly falls under the Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) and the broadcasting wing under Mediacorp. While not government-owned, the SPH is primarily influenced by the dominant political leadership in the country (George, 2012). Mediacorp, the broadcasting arm of the news, operates through grants and subsidies provided by the state (George, 2012). While SPH runs the Straits Times (largest English language newspaper) and The New Paper (packaged as a tabloid press), Mediacorp runs the Today newspaper (George, 2012).

Ranked at 158th on the International Press Freedom Index (Reporters without Borders, 2020), the mainstream media in Singapore is said to operate through various steps of control by the state (Tey, 2008), exercised through “political and punitive coercion” (p. 884). George (2012) conceptualizes the press as managed through calibrated coercion, where “Singapore can be seen as a textbook case of a state that has adopted a long-term view of power, deliberately reining in its use of force in order to build ideological consent” (p. 96). Tey (2008) discusses the state of the press in Singapore as pragmatic, where news is manufactured to pivot nation-building ideologies. Fundamentally, the press remains in harmony with the state, often working in consensus with state ideology (Tey, 2008; Kenyon, 2010; George, 2012). Therefore, the production of news is said to be deeply rooted in the machinery of the state. Critics and academics suggest that it remains challenging for journalists to operate through the Fourth Estate with limited freedoms of information laws, and “…a monolithic and cohesive state machinery that is not prone to leaks” (George and Venkiteswaran, 2019, p. 23). Out of bound (OB) markers determine what can and cannot be reported in the mainstream press (George, 2012). OB markers in Singapore (George, 2012) refer “… to the boundaries of political acceptability (p. 65)” in journalistic reporting and remains a central aspect of what is considered acceptable and responsible reporting by the state. OB markers are present because of the state's belief that journalism should be about shaping a core national identity and setting societal norms and agendas (George, 2012). The management of journalism in Singapore, according to George (2012), is sophisticated and calibrated through ideological control, rather than the use of overt coercion. George (2012) concludes that we cannot “overlook the power of ideology, and especially economic incentives, as tools of cooptation and control” (p. 25) when studying the news media in Singapore.

In an authoritarian context, the press takes a leading role in conveying public health messages (Schwartz, 2012; Basnyat and Lee, 2015). In Singapore, (Deurenberg-Yap et al., 2005) revealed that there was high trust in the state and its institutions in the management and knowledge transfers of the epidemic, despite limited knowledge about control measures and the SARS virus itself by Singaporeans. Kleinman and Watson's (2006) study of SARS in China, discussed the role of the media in a contentious relationship with the state, where issues of transparency and information control remained central in heightening the outbreak, revealing detrimental impact for news reporting. Leung and Huang's (2007) study of western led English media (including The Straits Times) on the coverage of SARS by China found that the ritual of othering was entrenched in Western media representations, reflecting the power dynamic present even as journalistic responses should remain balanced and accurate. The study found that the post-communist state was labeled inaccurately and unfairly in the handling of the SARS crisis, othering its political structure negatively.

Framing

Entman (1993) attempted to conceptualize framing amid a fractured understanding of the theoretical concept. How texts are communicated in the transfer of information by the media requires systematic analysis. Framing refers to how texts are selected and arranged for salience to communicate a “problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (p. 52). Entman (1993) states that the arrangement of text that both center sources of information, pose issues as problems, articulate stereotypical positions, and reinforce keywords tell us how frames are produced. Similarly, the rendering absent of positions also frame for readers schemas that inform how and what to think about specific issues. For example, Poirier et al. (2020) adopted framing analysis to make sense of how the Canadian media framed the COVID-19 pandemic. The study revealed that there were different key frames in the framing of the pandemic by anglophone media (Chinese outbreak frame) vs. francophone media (economic crisis frame).

Health communication frames by the press have been critiqued by Seale (2002) and Dutta (2008) for not merely portraying the known facts of viruses, but producing knowledge that centers specific racialized actors and engaging in information injections that politicize the health crisis. During the COVID-19 outbreak, Atlani-Duault et al. (2020) have called for health communication researchers to understand how perceptions in online discourses in shaping virus blame must be studied to mete out more robust health communication responses. Studying frames of mainstream reports give us rich insight into how invisible viruses conjure public health emergencies as racialized threats. In interrogating the role of the media in shaping discourses about migrant workers and public health, these research questions are posed, how did the mainstream media frame migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic? Whose voices were anchored in the discussion about migrant workers? How was migrant health discussed in the context of media as structure?

Culture-Centered Media Analysis

The culture-centered approach (CCA) studies the interactions of culture, structure, and agency to unpack issues of health marginality. It is predominantly offered as a meta-theoretical framework to study marginalized populations through ethnographic methods (Dutta-Bergman, 2004). However, the intersections of culture, structure, and agency have theoretically guided textually centered data in the analysis of discourses as well (e.g., Sastry and Dutta, 2012). For this study, the CCA provides theoretical input on the way communicative inequalities play out in the media's talk about the health of a subaltern group. With the CCA's roots deeply etched in the critical project of health in the margins (Sastry et al., 2019), the CCA is expressly concerned with identifying and mitigating asymmetries of power and control within spaces of knowledge production that are related to “health inequalities, the loss of health status, and the concomitant erasure of the voices and agendas of marginalized communities across the globe” (p. 2). The ontological commitments of the CCA theory are in unpacking how health is spoken about and defined, how health is discussed, and expressed by structural actors that limit the input of subaltern voices (Dutta, 2008).

The CCA provides a theoretical lens in making sense of how communicative inequalities play out in media infrastructures in the discussion of health about subaltern groups (Dutta, 2016). Several studies have adopted the theoretical tenets of the CCA to explore textual data relating to health, including media frames. Sastry and Dutta (2011), for example, critically interrogate media frames in the US mainstream news media in the construction of the Indian context of HIV/AIDS. Similarly, Khan (2014) studied media messages of public service campaigns about HIV/AIDS, adopting a textual analysis to unpack the discourse critically. Khan's (2014) study indicates the critical impulse required to show how messages reinforce the domination of subordinated groups. The CCA pays attention to how subalternity is created, perpetuated, and supported by the mainstream health discourses (Dutta, 2008). Mainstream media entities are one of the ways power structures determine the shaping of dominant health discourses in society. With the CCA providing a framework for a critical project, the mainstream is studied for how it reproduces absences, calling for us to pay attention to subaltern erasures in the circulation of dominant discourses about them.

In using this approach, this paper studies how mainstream discourses in the mainstream press reproduce communicative inequalities about migrant workers and their health disparities in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. The mainstream media infrastructure is read and interpreted as structural, where “discourse constitutes material inequities, justifying the poverty and silences at the margins of contemporary mainstream political economies” (Dutta, 2011, p. 14). Mainstream media is constituted as a medium of power, a shifting, dynamic, and a contested space where different actors in society clamor for spaces of representation (Dutta, 2011).

The mainstream press in Singapore serves as a conduit that circulates discourses entrenched in nation-building ideologies (Bokhorst-Heng, 2002). On migrant workers, the authoritarian neoliberal management of migrant labor is key to manufacturing the profitabilities to Singapore's economy in dominant discourse; hence, their surveillance (Kaur et al., 2016). A CCA critique would position the mainstream media as occupying a dominant state voice in its media messages, rendering absent the margins (migrant workers) in which it seeks to discipline and control. The critical bent of the CCA serves to critique the role of such mass media entities that are built into the logic of circulating dominant ideologies of health and social change. In using this alternative lens to make sense of media infrastructures, the paper employs a culture-centered media analysis that critically pays attention to how the media deploy erasures and absences in their reporting of migrant workers. Also, how agentic articulations of the margins are activated, represented, and portrayed by local media infrastructures. By theorizing media as structure, the CCA acts as a lens for how the relationships of power are sustained and re-circulated via media messages. The CCA reads a Marxist interpretation of structures, as institutions in our social system that create functions of inequity both materially and discursively for the vulnerable, and as sites that hold significant institutional power, erasing subaltern sectors from conditions of impoverishment (Dutta, 2011). Therefore, the CCA theorizes media institutions' as structural entities. Power is a central point of understanding the organization of media entities with the media structure co-opted by the state to serve its agendas. Thus, the hegemon of the mainstream media in Singapore is a potent site of erasure regarding discourses concerning the most voiceless and marginalized in Singapore society, leaving the margins intact when they remain unheard. How the othering practices of the mainstream media create further vulnerabilities for the margins require critical interrogation when dominant discourses translate into material disadvantages for the margins. With mainstream press as structure, are there openings for creating spaces for structural transformation by narrativizing the margins to be represented? How does the media organize structures in their storytelling of migrant labor? Communicative inequalities in the CCA refer to the absence or erasure of discourses from the margins, but also co-constructing discourses in the margins by prying open dialogic spaces, envisioning erased sites where communicative social change can occur (Dutta, 2011).

Method

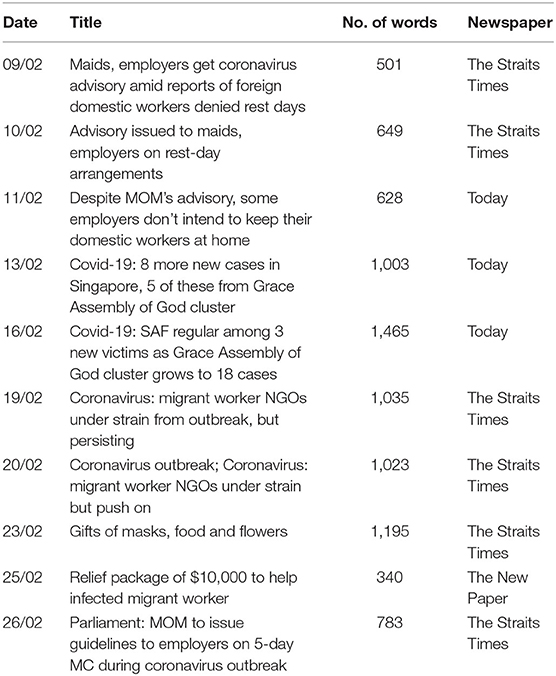

The study adopted a grounded theory analysis of n = 390 articles from three English-language mainstream newspapers in Singapore (The Straits Times, Today, and The New Paper). The article corpus was located through a search via a Factiva database using the terms “Wuhan Virus,” “Coronavirus,” “COVID-19,” and “migrant workers” from 5th January 2020 to 9th May 2020. The search paused on 9th May as episodic frames (infection clusters), and thematic articles (e.g., food, accommodation, treatment, structural conditions, treatment, voices) about migrant workers reached saturation with no novel categories emerging. Removed from the analysis were articles that did not centralize migrant workers in the Singapore context. This study specifically looked at low-skilled migrants (domestic workers and construction workers). Therefore, all articles that did not pertain to these two groups of migrant workers were removed from the search criteria. Other redundancies include articles related to migrant workers not located in Singapore or when migrant workers were mentioned for peripheral reasons (e.g., in an upcoming story).

The purpose of the study was to interrogate how migrant workers were constructed in the context of the COVID-19 crisis and public health in Singapore. Articles included forum letters, opinion pieces, and letters by the editors were all considered for analysis as they are central in the manufacture and production of dominant discourses about migrant work in Singapore.

Data Analysis

With the evolving COVID-19 crisis, it remained integral to study how the news shaped discourses about migrant workers to unearth new themes and frames positioned by the media. In adopting grounded theory to analyze news articles for theme development, this research was able to move beyond the already established categories on migrant worker frames (e.g., Hilsdon, 2003; Kaur et al., 2016; Kaur-Gill et al., 2019). Grounded theory analysis assisted with establishing inductive insight without pre-conception on themes and allowing for more significant discovery of how subaltern voice was erased or represented (Charmaz and Belgrave, 2007). By immersing, paragraph by paragraph, in examining the media content, I was able to detail both the patterns of voice were represented, along with the erasures. Erasures were coded for each article (absence, presence, and salience) when migrant worker voices were quoted in the news article (e.g., quotes, soundbites, names, visibility). In Table A1, I provide an illustration of the coding process.

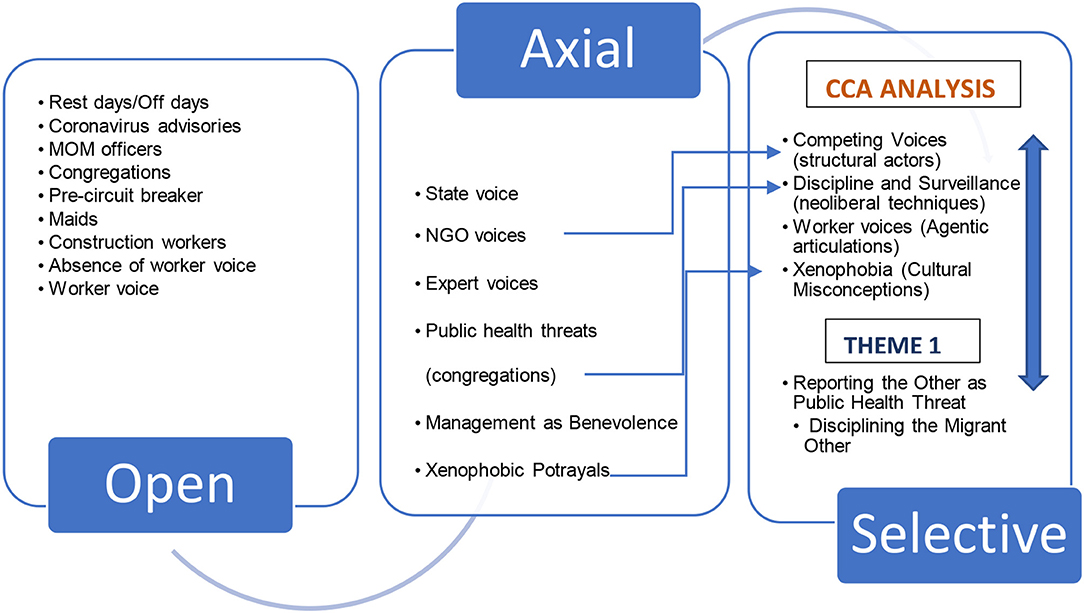

In connecting the open and axial (meanings to categories), conceptual ideas begin concretizing, developing the selective codes in the analysis (Charmaz, 2006). The axial stage involved studying carefully why certain concepts were discussed or positioned in particular ways, and how were specific meanings of interactions applied to the text. Part of the process included making sense of relational categories. The process allowed me to analyze the dialectics of discourses, representations, noting how the erasures of subaltern voice played out. At the selective coding stage, core categories remain clear in centralizing the discussions and tensions that appear (Bryant, 2017). The illustration of the coding process is reflected in Figure A1. A culture-centered analysis takes place at the level of selective coding conversation with grounded theory foregrounds the interplays of culture, structure, and agency in the construction of margins. Specifically, in the context of migrant health and well-being, a culture-centered analysis teases out the workings of structure, culture, and agency in the constructions of migrant health, where the analysis foregrounds how voice (agentic articulations) play out, attending to how migrant voices emerge and are centered in stories.

Three key themes are reported in the findings, Theme 1: Reporting the Other as Public Health Threat, Theme 2: Othering Cultures and Habits, and Theme 3: The Other Speaks Back. Emergent themes were discussed in conversation with CCA theorizing of communicative inequalities as structural inequalities, making sense of voice as agentic enactment in how mainstream discourses addressed quotations from various actors in its stories. The emergent themes were theorized using CCA's culture, structure, agency nexus on communicative absences, inequalities, and voice. Saturation of the conceptual categories were achieved when the media continued centering structural explanations in dominant stories about migrant workers and their health during COVID-19.

Findings

Theme 1: Reporting the Other as Public Health Threat

Migrant worker frames surfaced increasingly in media reporting during the COVID-19 crisis due to infections primarily afflicting the MCW community in the months of late March, April, and May 2020. MCWs were discussed as infection victims in mainstream reports. The structural conditions of migrant labor were surfaced in light of the surge in infection rates by the MCW community. The structural conditions of labor were only discussed when infection rates surged exponentially, crippling Singapore's international reputation as a model nation in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic in the earlier months. In late April and early May 2020, headlines regarding the structural conditions of migrant labor begin appearing, “Workers' dorms step up measures after 3 clusters emerge” (Yang, 2020) discussing their living conditions as a public health concern. Food received by migrant workers were another point of conversation, “Over 10 m meals served to foreign workers confined to dorms” (Tan and Ang, 2020). Finally, the crisis of infections among the MCW community took up mainstream news cycles at length. The conditions of migrant workers surfaced; specifically, the positioning of structural factors relating to migrant labor is attributable to the competing voices leveraged by the media in the championing for better treatment of MCWs discussed in Theme 3.

Separate categories on the rate of infections were reported for MCWs in the mainstream press. Community cases included all other categories of residents. The mainstream media obediently picked up these categorizations after state actors positioned for the press the discourse on two outbreaks, “Singapore facing two separate outbreaks: in the community and foreign worker dormitories” (Khalik, 2020). Reiterated in multiple reports:

Mr. Wong added that Singapore is “dealing with two separate infections” – one happening in dormitories where numbers are rising sharply, and another in the general population where “numbers are more stable for now” (Phua and Ang, 2020, para 6).

The separation of MCW infections from the general population were conferred to be epidemiologically necessary with an academic expert cited to clarify the separation:

Dr. Jeremy Lim, co-director of global health at the NUS Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, said on Wednesday (May 6) the Government's framing of Covid-19 as two separate outbreaks—one in foreign worker dormitories and the other in the community—was a “defensible” one from a public health perspective (Ho, 2020, para 2).

The argument positioned in the mainstream press revealed that due to the different strategies employed in managing workers' residing in dormitories, the infection categorizations as separate for MCWs versus residents were deemed unavoidable. The separation of categories, however, led to the discursive constructions of COVID-19 infections as largely othered in mainstream frames. Mainstream press centered state voice in positioning why the outbreak required the narrative of two curves, contributing to how MCWs were othered. As subjects for exclusion, workers remain relegated to the peripheries of the mainstream discourse even during the COVID-19 outbreak. The press re-circulated the techniques of othering by reinforcing the dual reporting of the infections instead of presenting datasets as national figures. The press did not critically interrogate how risk discourse is political, where limiting the communication of risk to the general public becomes a political strategy. Therefore, the communication of epidemiological insight is political, where the segmenting of a population to mark out difference during an outbreak is politically strategic (Lupton, 1993). How science is deployed for communication remains politically situated during a pandemic. Nevertheless, the mainstream press continued to reinforce the duality as necessary, carving out the peripheries of infections for its readers.

Information inequality among migrant workers was another frame that emerged in the early reporting of the pandemic and infections among MCWs. An article frames the narrative of information inequality specifically relating to health information seeking as being fraught for migrant workers. Citing an NGO spokesperson that “the language barrier makes it difficult for migrant workers to follow news developments about the outbreak. Many of them get their information secondhand, not always accurately” (Ho, 2020). The press begins cautioning readers about the challenges faced by migrants in health information translation. The othering practices in the representation of migrant workers as targets of misinformation or misguided information are selected. The mainstream press was also quick to report migrant workers as targets of fake news and misinformation:

With fake news spreading faster than the coronavirus itself among foreign workers, the Migrant Workers' Centre (MWC) has been relying on its network of volunteers who are also workers themselves to disseminate accurate information on the ground in a timely manner (Zhuo, 2020b, para 2).

Disciplining the Migrant Other

Early reporting also focused on MDWs singling out the community for congregating on their off day, “Maids, employers get coronavirus advisory amid reports of foreign domestic workers denied rest days” (Menon, 2020). The surveilling and disciplining of MDW bodies were picked up by the mainstream press in anchoring state voice in the distribution of advisories. In the early onset of the outbreak, the frame of disciplining the migrant other emerged in mainstream news. The frame remained the earliest shaping of the news regarding migrant workers relating to the COVID-19 outbreak. In tracing the discourse, mainstream press, specifically, The Straits Times begin circulating news on the surveilling of FDWs on their off day “Maids, employers get coronavirus advisory amid reports of foreign domestic workers denied rest days” (Menon, 2020) and “Advisory issued to maids, employers on rest-day arrangements” (Menon, 2020). Before the majority of infections were found to disproportionately afflict the MCWs (Ng and Ong, 2020), early media reports focused their attention on MDWs off days:

The advisory said households who have young children, the elderly or those with illnesses or special needs at home, may be concerned with the risk of transmission should their FDWs become infected while out on their rest day (Menon, 2020, para 5).

In this report, the mainstream press picked up on a state advisory cautioning against MDWs spending their day off in outdoor spaces. The day-off remains a contentious issue for MDWs. Only in 2013 were FDWs granted a mandatory day off, and this continues to be a site of negotiation for MDWs with their employers (Dutta et al., 2018). These advisories were followed up with notices to not go out on their off days, with Ministry of Manpower (MOM) officers breaking up migrant worker congregations, “Coronavirus: MOM triples ground efforts to disperse migrant workers who gather on Sunday” (Zhou, 2020b) and “Coronavirus: MOM will revoke work passes of migrant workers in large gatherings if they refuse to disperse” (Zhou, 2020a). This frame strongly cautions against migrant worker gatherings, urging “On Wednesday, MOM advised foreign workers to remain in their residence on rest days, and said their employers and dormitory operators should “educate” them on this” (Today, 2020). Disciplining the migrant other was seen in how the mainstream press, more specifically The Straits Times, remained unquestioning in their reports about why FDWs were subjected to such disciplining and surveillance when local Singaporeans were not. Two days later, on 11th February, a headline by Today, “Despite MOM's advisory, some employers don't intend to keep their domestic workers at home” (Today, 2020), begin critically engaging with various voices on these advisories. The article centered migrant voices as following social distancing rules yet were told to disperse by officers:

Ms. Ana Liza Dazo, 38, from the Philippines, was at the Kallang field to have lunch with her friend after remitting money nearby. “It's our day off and our employer said we could head out while taking care to observe the precautions,” said. These precautions included eating separately, not sharing utensils or drinks, and sitting more than 1 m apart. But this did not stop officers from asking her to pack up and go home (Zhou, 2020b, para 15).

Mainstream press while quick to report these advisories issued by MOM, centered alternative voices that touted such advisories as otherizing FDWs:

One employer Rose Awang, 57, told TODAY that it would not be morally right to restrict her domestic worker from going out even during this public health crisis. We go out very often. Children go to school every day. Why can't she go out,” the real estate professional asked” (Lim, 2020, para 9).

Here the article refers to a lack of restrictions on gatherings for residents, but advisories were issued to domestic workers not to head out or congregate on their rest days. The above quote positioned in the article signals to readers through employer voice how these contradictions surfaced. In othering workers, the disciplinary mechanisms issued by the state remained salient in the discussion of migrant workers in the mainstream press during the outbreak. These disciplinary strategies that adopt the language of health surveillance is a tacit strategy that has been employed to surveil the bodies of migrant workers that perpetuate their im(mobilities) in the host country (Dutta and Kaur-Gill, 2018).

Benevolent Actors and the Grateful Other

With migrant workers centering news articles in more pronounced ways by April 2020 due to the surge in the number of workers testing positive for COVID-19, othering techniques framed the role of the state and the migrant worker in mainstream reports. Reports included “Minister shares migrant worker's note of heartfelt thanks” (Cheong, 2020), where media reports shared the voice of state actors in highlighting worker gratefulness for aid received during the COVID-19 outbreak,

A Bangladeshi worker's heartfelt note thanking the Singapore authorities and those helping migrant workers deal with the Covid-19 outbreak was read out in Parliament yesterday by Manpower Minister Josephine Teo. Mrs Teo had highlighted the worker's gratitude after pointing out efforts by the Government, community groups and companies to help migrant workers here (Cheong, 2020, para 1).

State benevolence as frames in the mainstream press reflected the state's magnanimity for workers suffering in the peripheries of the city-state. Such frames were articulated periodically in the mainstream press. For example, the mainstream press presented recovering workers in stark contrast to dormitory conditions, “there are en suite toilets, in-cabin dining and strict infection control and safe distancing measure aboard the ship, as well as Wi-Fi, in-cabin entertainment and scheduled outdoor time” (Phua and Ang, 2020). These articles parlayed how the state managed and looked after MCWs during the recovery phase from COVID-19 on cruise ships. Mainstream frames were also quick to balm the conversations on the mediocre to poor quality of food received by MCWs. State voice were centered in frames about food such as the provision of food for migrant workers during isolation and confinement:

He (state actor) said there are 34 professional caterers providing meals to about 200,000 workers—akin to catering for the whole of Ang Mo Kio GRC. The Government is footing the bill for all meals in purpose-built dorms. It is not clear how much the caterers are charging but one of them, Neo Group, said it charges only for ingredients and labour costs (Tan and Ang, 2020, para 3).

NGOs and volunteers were highlighted for their acts of benevolence shown to workers,

Foreign workers have been the focus of this year's May Day celebrations as they make up a disproportionately large group of Covid-19 patients, and government leaders have assured them their health and other needs will be taken care of. Public agencies are also working with non-governmental organisations on these efforts (Yeoh et al., 2020, para 5).

Singaporeans from all walks of life also stepped forward to help, like Project Belanja, a community project to provide meals to migrant workers. “It is this resilience and cohesive spirit of our Singapore society—individuals, volunteers, front-line workers, businesses and many others—that gives me the confidence that we will overcome Covid-19 and emerge stronger” (Lim, 2020, para 10).

A variety of articles centered the efforts of NGOs and the local community in differing efforts to assist the disenfranchised migrant, “More than 35,000 masks have been sewn and will be distributed to workers through the Migrant Workers' Centre from this week” (Teng, 2020, para 17). Articles continued to portray the benevolence of the local community in stepping up for migrant workers, implicitly portraying migrant worker subjects as the “helpless other”. These frames of benevolence failed to interrogate the inequities faced by MCWs. The wearing of masks became mandatory by 14th April 2020 (Tay, 2020). The mainstream media had reported the provision of masks MCWs on 19th April 2020 in framing benevolent actors. These frames were manufactured to include how local corporate entities were stepping up for migrant workers, “A total of 400,000 migrant workers and 250,000 domestic helpers will receive face masks as part of efforts to improve the safety of foreign workers, said Temasek Foundation on Sunday (Apr 19)” (Today, 2020), without interrogating the discrepancies of mask distribution in the onset of the outbreak. Corporate and NGO entities stepping in to provide for the helpless other continue to circulate frames that remain uncritical of the state's management and response toward MCWs. This meant also centering advocacy efforts within the scope of service delivery, rather than narratives of structural overhaul. The free masks distribution exercise for residents were completed on 12th April 2020 with the eligibility criteria clearly stated as “Every resident with a registered home address can collect one (1) Reusable Mask each from collection points at designated Community Club/Centres (CCs) and Residents' Committee (RC) Centres” (Gov.sg, 2020). The mainstream media did not clarify if these residents included with dormitory addresses.

Separately, on 22nd March 2020, Today centered another story on migrant worker NGOs, titled “Covid-19: Sharp decline in volunteers for non-profit clinic, but migrant workers have reason for cheer” (Today, 2020), pointing to how grateful the workers were to be able to access healthcare through telemedicine, “Whether they get to see a doctor in person or not, migrant workers TODAY spoke to are simply thankful that they could still come to the clinic” (Today, 2020). Workers are depicted as grateful subjects, play to how the devices of othering operate in shaping outsiders and therefore, grateful subjects to the host country. The grateful subject is located within voices by state, NGO, and local actors.

It is noteworthy to mention that even when operating tropes of the “grateful other,” migrant worker conditions remained salient throughout news reports discussing benevolence. For example, despite re-narrating state voice on ensuring worker conditions improve, the mainstream press also framed the narrative of the grateful other concerning the poor conditions faced:

The Government has been criticised recently for the quality, quantity and type of food served to workers under lockdown. Several hundred thousand foreign workers have been confined to their dorms or other places of residence as part of efforts to curb the outbreak (Cheong, 2020, para 3).

The Straits Times reporting reintroduces frames on the poor conditions faced by workers even when centering frames of the helpless subject as the grateful other. Here the press re-circulated the continuing issues consistently on the questionable quality food received by MCWs. In reports about migrant workers, mainstream press shared, “The recent spike in coronavirus infections among migrant workers in Singapore has put a spotlight on the living conditions of a foreign workforce long invisible to many” (Ho, 2020). Thus, while mainstream press continued to uphold the state's efforts in combating the crisis with migrant workers and the COVID-19 outbreak, mainstream press, also pushed the OB markers, by constantly and consistently re-visiting frames regarding the structural conditions of labor via NGO voice or expert voice:

In a May Day statement, Home called for a close examination of the systemic issues affecting migrant workers and to take concrete steps to better their working and living conditions, and change biases and attitudes toward them (Yeoh et al., 2020, para 11).

Dr. Imran Tajudeen, from the Department of Architecture at the National University of Singapore, cited the lack of social integration of migrant workers, who may be housed in dormitories on the peripheries of society (Yeoh et al., 2020, para 14).

Frames on structural conditions surfaced and re-surfaced even in the presentation of the state and society's benevolence to the migrant subject. As previously discussed by Goh et al. (2017), these structural conditions were often always parlayed in tandem and not antagonism to state voice. Hence, the focus on their benevolence. The production of benevolence on frames about structural conditions operate to cooperate with the institutional logics of migrant worker advocacy. A rights framework remained absent in frames about migrant workers and the COVID-19 pandemic. Even when fundamentally advocating for a rights framework through expert voice, “Legalising a framework for worker-led and worker-owned unions and groups that represent the needs of low-wage migrant workers” (Wong, 2020), the direct pronouncement of a rights discourse were absent.

Theme 2: Othering Culture and Habits

The mainstream press published forum articles that singled out MDWs as subjects for containment, with these letters activating “dirty foreigner” tropes:

When meeting their friends, these foreign domestic workers take food and beverages that they have prepared at home to consume together at these gatherings. When they leave, empty food packs and drink cans are strewn at these places (Chin, 2020, para 2).

In engaging with such cultural tropes, the mainstream press published counter-narratives that sought to oppose such perspectives, including an NGO response denouncing such tropes, “it is unfair to target domestic workers and unnecessary to restrict their gatherings in public places at this point in time” (Kumar, 2020). Here, the mainstream press both created spaces for such tropes to play out, while also positioning alternative voices that referenced such letters as problematic.

As the pandemic manifested to afflict the MCW community significantly by April 2020, the mainstream press continued to discuss migrant workers in the context of cultures and habits. With a controversy erupting over the publication of a forum letter in the Chinese language mainstream press (a xenophobic letter about MCWs). The letter only led to further discussion on the cultures and habits of migrant workers in discursive constructions and circulation of them in mainstream news. The Straits Times picked up on the letter when a state actor cautioned that the forum letter was xenophobic:

A forum letter published in Chinese daily Lianhe Zaobao that linked the Covid-19 outbreak in dormitories to foreign workers' personal hygiene and living habits showed racism and deep insensitivity, Home Affairs and Law Minister K. Shanmugam said yesterday (Lim, 2020, para 1).

In furthering the frame, a Straits Times forum piece was published, denouncing the letter, “Forum: Culturally insensitive to refer to workers' eating habits as unhygienic” (Hoe, 2020). At no point, migrant worker voices were activated to respond directly to how dirty foreigner tropes about them were represented. Today, solely relied on state voice throughout its article to emphasize the xenophobic and racist nature of the letter, and to reprimand the letter writer for airing such views:

“I think the letter reveals some underlying racism. Because it typecasts an entire group—several hundred thousand of them—as lacking in personal hygiene, on the basis of their background, because they all come from backward countries,” he said in an interview with Lianhe Zaobao on Friday (Apr 17) (Mahmud, 2020, para 2).

While state voice emphasized the lack of understanding regarding transmissions among migrant workers, state voice was strategically framed to depict the letter as xenophobic:

Mr Shanmugam also said that the letter is xenophobic and deeply insensitive, and reflected a “lack of understanding of why we have this transmission of COVID-19 amongst our foreign worker population” (Mahmud, 2020, para 2).

NGO voice had begun cautioning against COVID-19 infections and stigmatization concerning migrant workers early. Even though a majority of infections became visible by late April 2020, early reports citing NGO voice begin framing for the reader, how migrant workers were potential targets of stigma relating to the COVID-19 virus:

Home executive director Catherine James is concerned that foreign workers may end up bearing the brunt of stigmatisation, given the intense paranoia about the disease, which was first reported in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December. In one case she encountered, a Chinese worker stranded in Singapore due to a salary claim was unable to find a dormitory that would take him in and wound up sleeping in an Internet cafe until Home found him shelter (Ho, 2020, para 26).

NGO voice was utilized in mainstream reports to sound the alarm on the plight of migrant workers. We see the outbreak inequality narrative forming by 3rd April 2020 (Yang, 2020). Frames of culture and habits were played up in the narratives that discussed the possibilities and impossibilities of integration of migrant workers with the local community by NGO and expert voices:

Ultimately, said MWC's Mr. Menon, it takes two hands to clap and society must be more accepting. “We have tried to rally the migrant workers to interact and hopefully integrate with Singaporeans, but learned quite a painful lesson over time that integration is a two-way street” (Ho, 2020, para 2).

The mainstream media presented for the readers how the tools and techniques of othering about migrants were pivoted in mainstream discourse. Here, a state-affiliated NGO voice discussed the challenges of integration of migrant workers by speaking to how Singaporeans exclude MCWs, “If we don't have an equal number of Singaporeans willing to welcome and accept them, it's very difficult” (Ho, 2020). Other articles pushed further, by directly addressing the prejudices of culture and habits in comparison to the lives of Singaporeans as not being too different,

Never mind the fact that they gather under trees or on fields because there are often no accessible or affordable places for these workers to take a breather after a hard week's work, in the same way that Singaporeans kick back with beers with friends in kopitiams, bars or at home (Yuen, 2020, para 13).

Here Yuen (2020) does not only seek to address xenophobia toward migrants but provides a structural explanation rather than a cultural one in tackling unfounded fears about their behaviors by Singaporeans. In Kaur et al. (2016) previous research on migrant worker portrayals, the mainstream press connected cultural explanations in shaping the constructions of MCWs in conflict with state voices. Here we see a shift in how MCWs are discussed more specifically as victims of structural injustices rather than adopting a cultural explanation for their behaviors.

Dormitories as Spread and Contagion

Central to mainstream reporting about migrant workers were dormitories as a site of spread and contagion, “Migrant workers living in dormitories continue to be the most severely impacted demographic, comprising the majority of the remaining cases” (Yang, 2020). The discursive construction of dormitories as spread and contagion sought to provoke discussions on the responsibility of various actors for the poor treatment migrant workers in the city-state. One the one hand, press reports centralized the roles of dormitories as sites where social distancing was required, “Coronavirus pandemic; Stricter rules at foreign worker dormitories to enforce safe distancing” (Tan, 2020), with another article discussing strategies of containment:

Dormitory operators should also monitor the health of residents in blocks, limit their movements and prevent mixing of workers between blocks. They must stagger timings for kitchen and shower use, and limit the number of people in recreational rooms and minimarts. Operators must also put up signs telling workers not to gather at common areas (Tan, 2020, para 6).

Keeping workers within dormitories as a strategy for containment as problematic was reported by The Straits Times, framing the conditions of the dormitories that make social distancing challenging, “Coronavirus: Workers describe crowded, cramped living conditions at dormitory gazetted as isolation area” (Lim, 2020). Mainstream press emphasized the conditions of dormitories as sites of spread, framing dormitories as a threat to public health for workers,

At least six workers at the S11 Dormitory @ Punggol, where there are 63 confirmed cases of Covid-19, told The Straits Times that the rooms are infested with cockroaches and toilets are overflowing. Workers have to queue for food with no social distancing measures to keep them apart (Lim, 2020, para 2).

The article discusses the dehumanizing conditions of the dormitory and the locking down of workers in these spaces,

Mr. Venkate said officers from the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) visited the dormitory last Saturday night and, at around 9 p.m., one announced that the dormitory would be fully locked down, with no one allowed to leave the premises (Lim, 2020, para 2).

Dormitories thus, were both discussed as a site where the spread of COVID-19 infections took place rapidly due to the poor conditions that enabled the surge in infections:

His comments came as the foreign worker community here has been hit hard by the c coronavirus pandemic, with more than 2,600 workers in large dormitories infected. There are about 200,000 migrant workers in these purpose-built dormitories (Wong, 2020, para 6).

In the quote above, a spokesperson from a state-affiliated NGO cites the scale and spread of infections in dormitories. These sites also became the space where illegal confinement and poor treatment of workers were amplified. NGO groups sounded the alarm on the confinement of 20 workers, “A dormitory operator who forcibly confined 20 workers in a locked room had been given a stern warning from the Ministry of Manpower (MOM)” (Zhuo, 2020a) that was picked up by mainstream media. With a lack of space in dormitories and a positive Covid-19 worker, “the reason given by the operator was to prevent them from moving around after a close contact was confirmed positive for Covid-19,” said the MOM (Zhuo, 2020a).

The reporting of dormitories by the mainstream press, presented competing voices regarding the state of dormitory conditions. These competing voices called out the severe structural reasons for the spread of infectious disease, as well as the limitations of these sites for containment and isolation of workers. The inmate treatment in the design of dormitories (Rubdy and McKay, 2013) and peripheral locations of these dormitories are reported extensively. An article by Today published a study on worker treatment during the COVID-19 crisis. The article anchored academic voice to critically interrogate the othering practices embedded in the ideological construction of these dormitories in peripheral and marginal ways, “the power held by the employers and dormitory owners, accompanied by the absence of transparent and safe infrastructures for raising complaints translates into unhealthy structures remaining intact,” he wrote in the white paper (Today, 2020). The article presented the interest of various actors that amplified the public health threat within the dormitories of MCWs.

The dormitory as news frame remained in the spotlight in the discussion of migrant workers, where the dialectics of spread and contagion remain absent in the analysis. The structural conditions of the dormitories also continued to occupy media narratives, discursively engaging with the concept of peripheral dormitories and migrant workers. Headlines in May 2020 reinforcing “structural and mindset changes needed to improve wages and living conditions of foreign workers, say analysts” (Ho, 2020). Expert and academic voices were referenced in the presentation of dormitories as underlying structural conditions that remained a public health threat for workers in the short-term and long-term:

“These infrastructures are not adequate as there are often long queues and the facilities remain unclean,” Prof. Dutta wrote. All in all, the responses do point to the existence of “unhealthy structures” which “most likely” contributed to the further spread of Covid-19 in the foreign worker community, Prof Dutta said (Ho, 2020, para 27).

Improving the wages and living conditions of foreign workers in Singapore requires a whole-of-society effort. Not only must the Government take the lead in making structural changes, but Singaporeans, too, must change their us-versus-them mindset, said analysts (Ho, 2020, para 1).

Dormitories, dormitory operators, employers, and the dormitory regulators were discussed as key structural actors in the management and spread of the virus among MCWs. While mainstream press did not interrogate the dialectics of spread and contagion, the press extensively discussed the role of dormitories as unsanitary, inhuman, and a public health risk for migrant workers (Tan, 2020).

Theme 3: The Other Speaks Back

While in other previous literature, migrant worker voice remained in the margins of mainstream discourse (Kaur et al., 2016; Tan, 2016), worker voices were spotlighted in moments of this health crisis as rupture points. These voices were anchored in a few ways. In spotlighting their structural conditions, foreign worker voice appeared and re-appeared in moments of heightened surveillance of their conditions during COVID-19 as a public health threat. Voices were centered in the discussion of their living conditions:

“There are many cockroaches in the kitchen and also in our rooms. The urinals in the toilets are overflowing with urine and the workers step on the urine and then walk to their rooms,” said Indian national Venkate S.H., 34 (Lim, 2020, para 11).

Worker voices were anchored in the discussion of fear of spread and contagion in dormitory settings,

“On Sunday, most of us woke up at 8 a.m. and were waiting for our breakfast, which arrived at about 10 a.m. Everybody queued together to get the food. There was no social distancing. We also did not have masks. Only a few workers had their own masks” (Lim, 2020, para 17).

Voices of workers were used to deploy serious public health issues that threatened the rapid spread of infections in the migrant worker dormitories when reports of infections begin surging in the city-state and the abysmal absence of information regarding the lockdown:

Said Mr. Venkate: “This happened suddenly. We did not stock up on food. I can't go out to buy my coffee. But some people have food and they were cooking in the kitchen because dinner was still not here at 8 p.m.” (Lim, 2020, para 21).

Migrant worker voices were deployed to break the news about the conditions of the dormitories, but were also activated to humanize workers,

We want our writing to change locals' views of migrants and also migrants' views of themselves, “he says. All everyone thinks is that we do dirty, dangerous and difficult work. But we can also be poets, photographers, film-makers. We can be inspired by what we do” (Ho, 2020, para 12).

The Straits Times piece created space for the margins to activate for themselves by speaking back to Singaporeans about who they are beyond just the label of MCWs. The article fronted how MCWs were also volunteers,

In the days before he fell ill, he was volunteering with grassroots initiatives to rally donations for workers restricted from leaving their dormitories during circuit breaker measures and organise the distribution of supplies, such as masks and sanitisers, to them (Ho, 2020, para 15).

In humanizing workers by creating space for their voices to speak back to tropes about them, mainstream press can be seen pushing the OB markers for critical voices from the margins to be heard. Even in Today's reporting of MDW movements during their off days, mainstream press anchored MDW voice to disrupt the single thread of state voice regarding the advisories, “it's also status quo for Ms. Cristina Mandoza Fayco, a 57 year-old domestic worker.” “My boss never said anything to me like, “Don't go out” or “Don't do this or that”,” she said (Today, 2020). Mainstream press configured reporting practices as radical moments for the margins, centering competing actors as voice, while also in moments of crisis voices of the margins for more considerable change and advocacy.

Humanizing the Other: Structural Conditions of Labor

As the COVID-19 situation develops in Singapore with the number of cases crossing 25,000 by early-mid May 2020, the media actively centers and discusses migrant worker health with the bulk of infections afflicting the MCW community. With headlines such as “Covid-19 outbreak brings migrant workers from margin to centre of Singapore's attention” (Yuen, 2020), suggests the mainstream media was attentive to migrant worker treatment in Singapore. Articles such as Yuen's (2020) points the reader's attention by dispelling prejudices about migrant workers, concluding for the readers

Migrant workers are part of our community. Covid-19 has brought them front and centre into our lives. It is time we stopped pushing them to the margins and started the hard work of integrating them better into our society (Yuen, 2020, para 52).

While the discussion of the margins remained the center of this story, the agentic voices of migrant workers remained absent even when articles chose to position the margins as a frame for readers. The structural conditions of labor are highlighted and reinforced throughout the article to unpack the very conditions of labor that limit migrant worker health,

Most Singaporeans turn a blind eye to this invisible class of workers, who are out of sight and out of mind. Many locals are unaware of the structural issues they face in terms of housing or welfare. The issues in the past—the lack of trust and interaction between the different groups—remain buried (Yuen, 2020, para 36).

The voices of multiple experts were presented in news articles in discussing structural conditions of labour, including academics and NGOs. Headlines in May 2020 focused on “Structural and mindset changes needed to improve wages and living conditions of foreign workers, say analysts” (Ho, 2020), “Solving Singapore's foreign workers problem requires serious soul searching, from top to bottom” (Ng and Ong, 2020), and “Migrant worker housing: How Singapore got here” (Ng, 2020). These articles fronted quotes from academic experts and NGO voices in discussing better treatment and solutioning through systemic changes in the management of their labor. These articles predominantly surfaced in late April-early May, where the majority of infection clusters were located, sites where migrant workers reside and work. Citing academic studies, a Today article, for example, cited surveys conducted with migrant workers on their current needs, “Almost eight in 10 workers also find it a challenge to maintain a 1 m distance from others due to “cramped conditions” at their dormitories, the survey found” (Wong, 2020). On the discussion of structural conditions, the mainstream media highlighted dormitory conditions, worker wages, the economic model for the management of migrant labor, ethical, and moral obligations in the treatment of migrant worker rights, and health conditions. For example, Today reports,

With Singapore now facing what has been touted as “a crisis of a generation,” some, like Assoc Prof Theseira and fellow NMP Anthea Ong, have called for a committee of inquiry into the foreign worker dormitory outbreak to work out the structural changes that Singapore sorely needs (Ng and Ong, 2020, para 111).

This quote was presented under a sub-heading titled “Tweaking Singapore's Economic Model” (Ng and Ong, 2020) in the article, highlighting the need to review the current system of labor management. A Straits Times piece captures a quote from an expert,

But a whole-of-society mindset change is needed for the support to be sustained, said Dr. Lim. “The mental model we have traditionally taken is that foreign workers are part of the community but separate; we accept that there should be different standards (for them)” (Ho, 2020, para 7).

In centering such voices of change, these articles articulate radical shifts in how migrant workers are treated in Singapore. Ng and Ong (2020) humanized workers by including their narratives and centered their lived experiences in the report:

Mr Liton has reason to be worried—two of his friends, Asit and Zakir, who live in the larger purpose-built dormitories, have been diagnosed with the disease and hospitalised. We all want to go home in good health … My wife miss(es) me more and more, he said (Ng and Ong, 2020, para 5).

While Mr Liton ponders over the future, his host country—Singapore—will also have to reassess its whole relationship with migrant workers like him, especially its “addiction” to cheap migrant labour, and examine whether the lessons learnt from the explosion of COVID-19 cases in the workers' dormitories could be used to implement meaningful changes (Ng and Ong, 2020, para 10).

Efforts by Ng and Ong (2020) in reporting through voices of the vulnerable shift the lens in which migrant workers are relegated to the margins for audiences in mainstream discourse.

Discussion

The mainstream press in Singapore is theorized as a structural entity in close affiliation to the state's reprimand (George, 2012; Dutta et al., 2019). However, during the COVID-19 crisis, the role of mainstream media in reporting the margins revealed moments of ruptures where the media created openings for an in-depth discussion on low-wage migrants and their structural conditions that require change. From a CCA perspective, the discussion of structural conditions of migrant workers points to critical transformative openings by the media that are anchored in structural changes on the systems of hire of migrant labor (Kaur-Gill and Dutta, 2020). In pandemic response, mainstream media created openings in the discussion of these possibilities in dominant communicative spaces.

By centering competing voices that curated a variety of different threads on migrant workers and the COVID-19 crisis, structurally-centered articles about their treatment in Singapore society were located by early May 2020. Migrant worker voices were activated in shedding light on the hazardous labor conditions discussed extensively in mainstream reports in April and early May 2020. Conflicting and contending positions articulated by expert voices (civil society and academic experts) created avenues for structural factors to emerge as salient in discussing the underlying conditions the exacerbated infections among the migrant worker community.

Mainstream Media, the COVID-19 Pandemic and Transformative Openings

The mainstream press in Singapore has been rebuked for the presentation and selection of frames that propel narratives in participation with the state's public relations performance, limiting room for frames that provide alternative rationalities and realities of the margins (George, 2012). In the reporting of the COVID-19 crisis and migrant workers, the hegemonic tropes are laid out for consumption, while also pushing for dissident discourses on migrant worker issues. Reports by both Today and the Straits Times pushed the OB markers by challenging the status quo of worker labor conditions, where competing voices did not fall in line with state narratives on the discussion of migrant workers as in the past. During the COVID-19 crisis, we see how the media structure in speaking for the agendas of the powerful were disrupted. Transformative openings, where agencies of the vulnerable are not just discussed, but activated. Worker voices were presented but also activated in agentic ways in news reporting in the mainstream press. While on the one hand, the media structure continued to perpetuate the status quo, as the state's mouthpiece on issues on migrant workers and their health. Under conditions of this pandemic, moments were located where the media structure created openings for the discussion of the margins in transformative ways where the media structure reflected sites of transformative openings in its discussion of the margins. The media created space for advocacy tied to the structural conditions of labor, highlighting systemic changes required for the better treatment of migrant workers, but also discourses that centered a need for moral and ethical change in the treatment of migrant workers in Singapore. This finding might potentially indicate a shift in the frames of discourse on migrant worker advocacy as culturally mediated vernacular reported in Koh et al. (2017) study. The timeline of how the crisis played out provides perspective on how shifting discourses on migrant worker health were discussed at different stages of news reporting. When expert and NGO voices dialogued about these issues on various forums, the mainstream press was quick to anchor these voices on articles about structural conditions of migrant workers in Singapore by citing these forums and webinars.