- 1Sociology, Social Policy and Criminology, Economic, Social and Policy Science, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Life and Environmental Sciences, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, United Kingdom

- 3School of Geography and Environmental Science, Faculty of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

- 4Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

The management of coastal flood risk is adapting to meet the challenges and increased risks posed by population change as well as by climate change, especially sea level rise. Protection is being targeted to areas where the benefits are highest, while elsewhere there is a shift towards more localized “living with floods” and “resilience” approaches. Such decentralized approaches to flood risk management (FRM) require a diverse range of stakeholder groups to be engaged as “flood risk citizens”. Engagement of households in FRM is central to this process. Despite significant research on stakeholder engagement in coastal and flood risk management, there is less focus on the nature of responsibility in coastal adaptation. There is no framework by which to assess the different types of responsibility in hazard management and adaptation, and little research on the implications of expecting these responsibilities of stakeholder groups. In this paper, we identify five types of responsibility that are embedded throughout the disaster risk reduction cycle of managing coastal flooding. We build this “typology of responsibility” on existing work on the evolution of stakeholder engagement and stakeholder responsibility relationships in risk management processes, and a dataset of institutional stakeholder interviews and households surveys conducted across three case studies in England, the United Kingdom, in 2018 and 2019. We analyze the interviews using thematic analysis to explore institutional stakeholder perceptions of responsibility in coastal FRM, and analyze the household survey through descriptive and inferential statistics. By developing the first disaster risk reduction focused typology of responsibility for coastal flooding, we provide researchers and decision-makers with a tool to guide their planning and allocation of responsibilities in risk management for floods and other climate-driven hazards.

1 Introduction

Flood risk governance, the collective management of flood risk (Alexander et al., 2016), includes the efforts of diverse societal actors to address the problems and benefits of flood risk (Huitema et al., 2016). In contemporary flood risk management (FRM) around the world, that governance also requires consideration of the changing nature of flood risk – driven largely by climate, demographic and development drivers (Neumann et al., 2015; Nicholls et al., 2015). Despite the pressures that are increasing the coastal flood hazard and exposure, there remain few examples of adaptation policy and action in practice to sea level rise globally (Bongarts Lebbe et al., 2021). To adapt the flood risk cycle to this changing context, a shift from resistance to risk resilience and a decentralization of decision making from the center to the local are increasingly proposed across Europe (Gersonius et al., 2016; Schanze, 2016). The shift toward a resilience paradigm is further demonstrated in the latest National Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Strategy for England, with no fewer than 302 mentions of resilience, and the inclusion of a £200 million program of innovative resilience programs for delivery between 2021 and 2027 (EA, 2020).

Inherent to the decentralization of FRM is the transfer of “responsibility” across stakeholders. The inclusion of local stakeholders, and specifically households, is proposed to: integrate their knowledge for improved decision-making processes (Pasquier et al., 2020), encourage uptake of property level measures (Begg et al., 2017a; Snel et al., 2021), and aid the rapid adaptation required to meet changing flood risks (Begg, 2018). Despite a significant body of research on stakeholder engagement in flood resilience, there remains very little work explicitly on the characterization of responsibilities in the FRM cycle (Morrison et al., 2017). In developed countries it is acknowledged that responsibility framings in disaster risk governance are changing. Examples include: in Australia, with disaster resilience being a “shared responsibility” between government sectors and society (McLennan et al., 2014); in Germany, with households being expected to take measures to prepare and adapt to flood risk (Bubeck et al., 2012); and in England, with a changing balance in FRM between the private and public domain in the context of “Making Space for Water” and in terms of “partnership working” on the coast (Johnson and Priest, 2008; Blunkell, 2017).

The transfer of responsibility has been discussed in FRM literature (Johnson and Priest, 2008; Butler and Pidgeon, 2011; Begg et al., 2017), but there has been little attempt to specifically identify and define the types of responsibilities under consideration. McLennan and Handmer (2012) responsibility continuum between self-reliance and central authority responsibility is one of few examples. However, this is developed specifically for bushfire risk and focuses on the spectrum of responsibility sharing between self-reliance and central-authority, but does little to distinguish between types of responsibility in terms of their origin and nature. More recently, Snel et al. (2021) describe a typology of responsibility – prior to or after events – in relation to flood events (not flood risk). Their typology is primarily based on a binary of “before” and “after” the flood, and does not explicitly consider the widely accepted conceptualization of flood disasters as a cycle (risk mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery) within which institutions are embedded (Begg et al., 2015; Morrison et al., 2017).

In the English coastal FRM context, the shift from flood protection through to resilience paradigms forms part of a longer history of evolving practices of managing coastal flooding. Coastal management prior to and during the early twentieth century is often characterised as a period of flood protection, dominated by the goal to prevent and resist flood events (Lumbroso and Vinet, 2011; Alexander et al., 2016). As a result of significant progress in coastal flood defenses, spatial planning, and improvements to flood forecasting, warning and emergency response, the consequences of coastal flooding in the UK have reduced over the past century (Haigh et al., 2020). The transition from protection to risk management during the latter half of the twentieth century saw a shift to an approach comparable to the disaster risk reduction cycle, encompassing not only prevention and defense, but early warning and preparedness, response and recovery, and learning (Alexander et al., 2016; Haigh et al., 2020). However, the rise of flood risk management was accompanied by an increased role for the citizen in addressing coastal flooding, such as in their responsibility to know what to do and be prepared for coastal floods (Butler and Pidgeon, 2011). The twenty-first century has since seen an ongoing movement toward the “resilience” paradigm in coastal FRM (EA, 2020; Townend et al., 2021), which encompasses an even greater emphasis on holistic, systems-approach to addressing coastal flooding, as well as entails a further “responsibilisation” of citizens in the coastal FRM cycle (Vilcan, 2017; Snel et al., 2021). Pervasive throughout all paradigms, however, is the question of who is responsible for what, and how responsible stakeholders are supported in actualizing these expected obligations.

In England, 520,000 properties are located in areas of 0.5% or great annual risk from coastal flooding, it is almost certain that England will have to adapt to at least 1m of sea level rise at some point in the future (CCC, 2018), and the possibility of exceptional storm events must also be considered (Horsburgh et al., 2021). Adaptation to these risks should be considered proactively in long-term land use planning and coastal defense strategies, and integrated across wider coastal management actions. These are not vague, distant future actions and it should be a priority in terms of policy and practice to integrate adaptation now, offering long-term benefits in terms of lower costs and more effective action. (CCC, 2018). In the English context, centralized protection-based FRM is increasingly not universally deliverable and affordable in this risk society context, especially for smaller coastal communities (Sayers et al., 2022). Funding to deprived areas has reduced since 2014, and despite significant future capital investments from Government into flood and coastal defenses there remains a dependency on more uncertain funding sources to deliver its long-term aims (National Audit Office, 2020). In addition, regardless of resistance, risk and resilience approaches and measures, a residual risk of coastal flooding remains in all defended flood plains. Similarly, the current paradigm of systems-thinking resilience approach is evolving rapidly and will see changes in future years, dependent on private and public decision-making on how to manage the coast. Nevertheless, there has been scant attention paid to the types of responsibility assumed of various stakeholder groups in the past nor present. It is imperative to improve our understanding of responsibilities in addressing the risk of coastal flooding to be ready for the future.

We expand upon the Snel et al. (2021) framework to propose an enhanced typology of household and institutional responsibility for coastal FRM, drawing on the cyclical disaster risk reduction conceptualization to identify types and implications of stakeholder responsibility in FRM. We also consider empirical work showing that households adapt when they feel responsibility and have the capacity to do so (Koerth et al., 2017). An increasing number of studies model the relationship between explanatory variables and household adaptation behaviors, but the role of responsibility in this process, especially as affected by institutional management actions (such as engineering interventions or insurance access), is still underexplored. Using mixed methods we analyze three case studies in England, United Kingdom (UK), to assess local institutional stakeholder and household perceptions of responsibility for coastal FRM. Whilst there is an increasing understanding of the importance of clear responsibility attributions to stakeholders in disaster risk management and adaptation, there is not yet an overview of the range of responsibility types and their implications. By constructing the first such disaster risk reduction informed framework, we provide researchers and decision-makers with a tool to guide their planning and allocation of responsibilities in management of multiple natural hazards risk, although our focus is on coastal flooding.

2 Materials and methods

In England, people on the coast remain largely uninvolved in planning for future change (CCC, 2018), and awareness of flood risk and uptake of household flood defenses are both low (Everett and Lamond, 2013). Nevertheless, responsibility for flood risk adaptation is increasingly being transferred to the local level, such as through: the responsibility of citizens and householders to accept and manage their own flood risk, localization of cost-sharing through the Partnership Funding scheme, and decision-making relating to the selection of FRM-related measures (Johnson and Priest, 2008; Penning-Rowsell and Johnson, 2015; Begg, 2018). Partnership Funding, for example, was established in 2011 and requires third-party “partners” to raise additional contributions to fund flood schemes if the not all of the finance required will not be provided by the national government (calculated based on the benefits and outcome measures met). The government Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and agency Environment Agency (EA) have prioritized “responsibility” as a community engagement issue, and the Pitt Review 2008, conducted following devastating river flooding in 2007, also identified a need for householders to “properly consider risks and take precautionary actions” with regard to flooding generally (Pitt, 2008, p. xxxi). Nevertheless, there remains a disconnect in England between national FRM policy and household engagement in FRM (Alexander et al., 2016). To better understand how responsibility is perceived in coastal FRM policy and practice, we collected data across three case sites in England, with qualitative interviews in two areas and quantitative household surveys in the third area (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Counties forming the case sites for this study on north-west, south and east coasts of England, UK, for data collection in 2018-2019 using data from Office for National Statistics 2017).

2.1 Study area

The coastal case sites are based in the (1) north-west, (2) south, and (3) east coasts of England (see Figure 1). In two sites (1-2), a qualitative data collection and analysis approach was taken, with the completion of forty-five semi-structured interviews with key institutional stakeholders. We distinguish individual households from other stakeholder groups such as local groups, local authorities, and national public bodies; the latter we refer to as “institutional stakeholders.” In the remaining site (3), a quantitative approach to collect data from residents was taken, with data collection through a household survey and statistical analysis of the resulting dataset. All three areas are exposed not only to coastal flooding, but also to fluvial, surface water and compound flooding, as well as erosion.

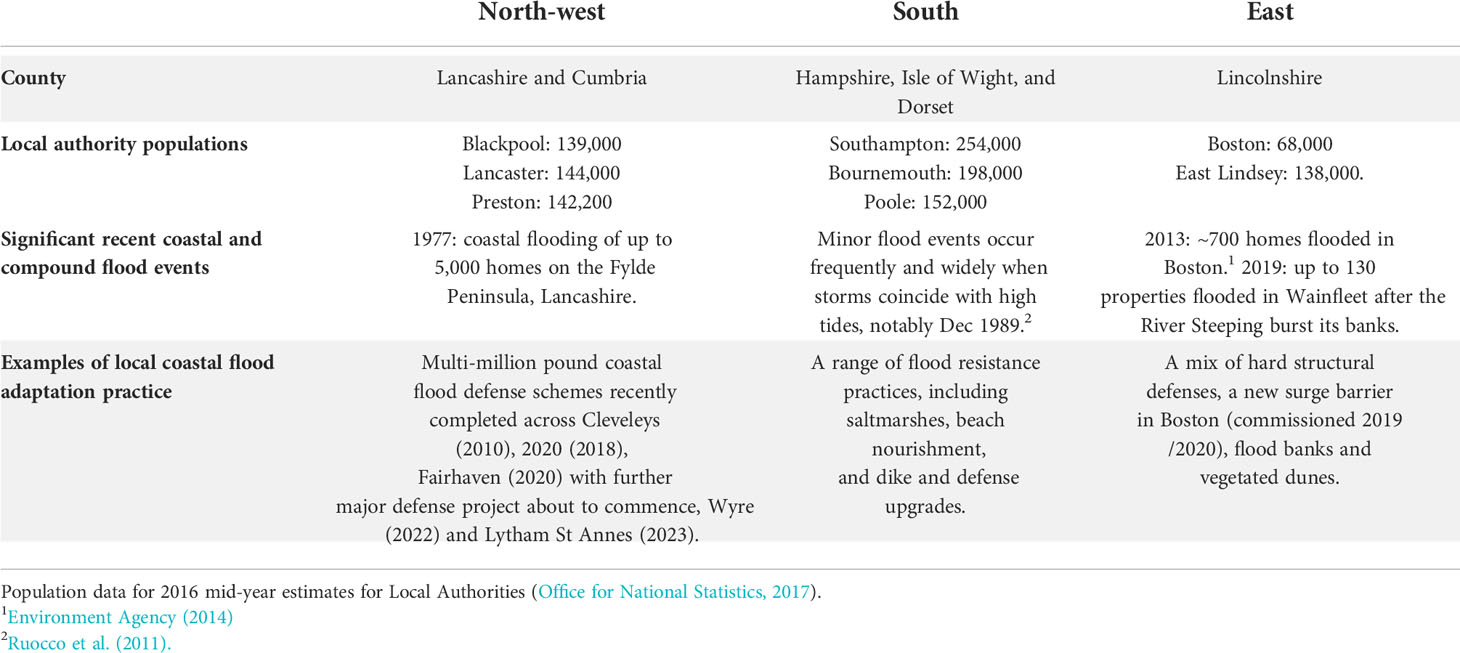

The three cases utilized in this work were selected from a shortlist of English coastal areas that have recent coastal flood history (defined as the past 100 years) (Haigh et al., 2015; Haigh et al., 2017), contain coastal towns of average size (defined as being in the interquartile range for population, of towns with recent flood history), and from regions with distinct coastal flood footprints (Zong and Tooley, 2003; Haigh et al., 2016). Further factors considered in case selection include the flood risk and exposure in each area (types of flooding and exposed assets), the flood history (frequency, severity and most recent flood events), flood defense and management history (e.g., soft and hard engineering, recent spending), and socioeconomic factors (e.g., average age of the population, levels of deprivation) (see Table 1). The three case studies were chosen from this shortlist based on their representing distinct geographies within the English context (north-west, south and east), differing physical coastlines (larger and smaller coastal floodplains with differing levels of river flood risk), and each site containing contrasting population distributions (cities, suburban and rural).

2.2 Thematic analysis of key stakeholder perspectives of responsibility in FRM

2.2.1 Semi-structured interview data collection

Semi-structured interview data was collected throughout 2018 with institutional stakeholders from the south and north-west coasts (van der Plank, 2020). There is a range of responsibilities across diverse stakeholders in coastal FRM, both mandated and implicit, but we lack a broad understanding of the expected roles and responsibilities of households and local stakeholders to manage coastal flood risk (van der Plank et al., 2021). Through engaging directly with key, local institutional stakeholders, we sought to explore how local stakeholders (here defined as stakeholders operating at sub-national scales) consider their own responsibilities and that of other stakeholders in the context of coastal FRM. A stakeholder analysis, whereby stakeholders are selected according to their influence and importance to the specific project or process (Prell et al., 2009), was used to identify and select interviewees, and the initial group was built on with the recommendations from participants (“snowballing”) until the same narratives began to be recorded in the interviews (“saturation”).

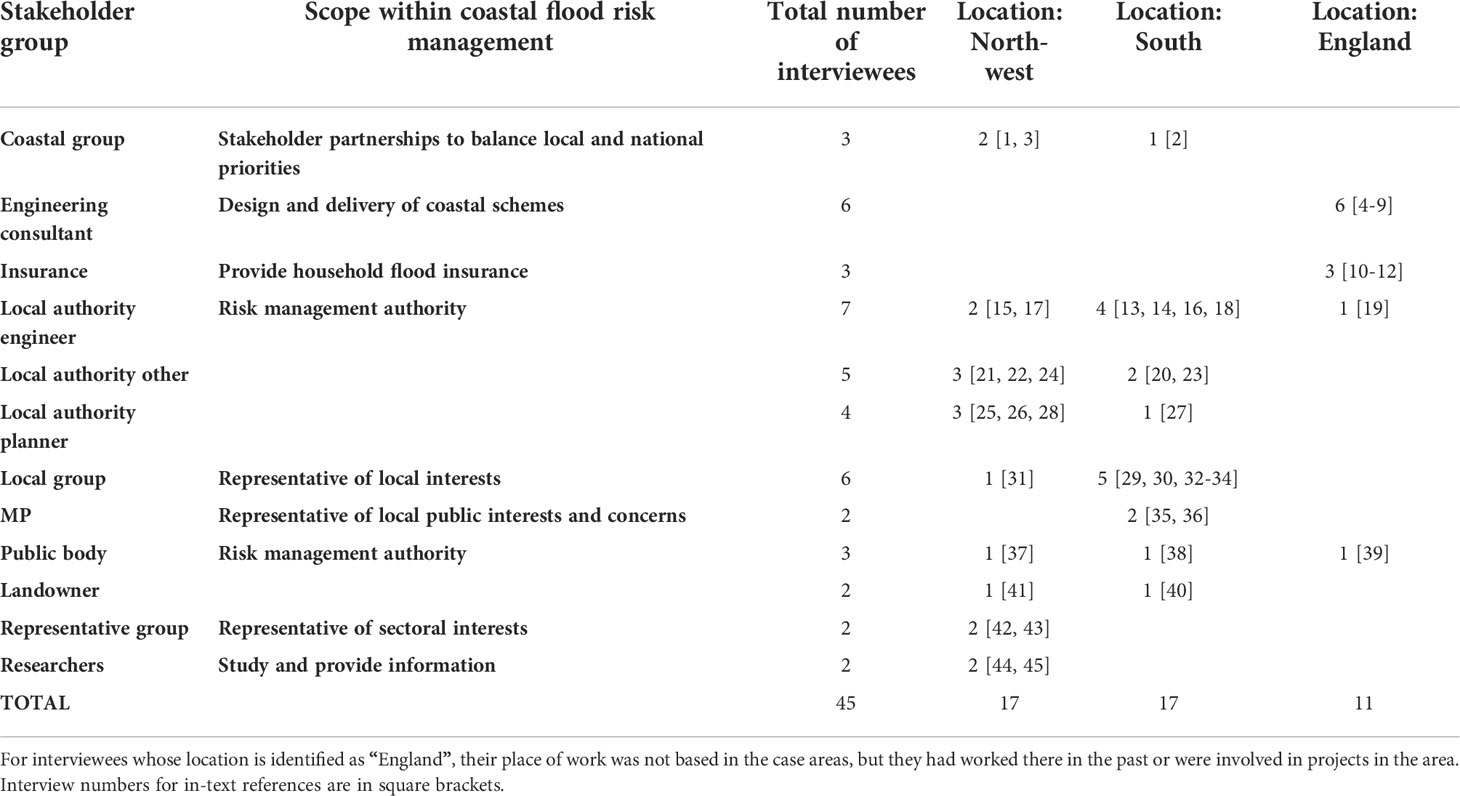

Key institutional stakeholders (henceforth, “institutional stakeholders”) engaged in this study include coastal and flood engineering consultants, coastal groups, insurers, local authority employees, local community and parish council groups, public bodies (e.g. Defra and the EA), MPs, landowners, representative groups (e.g. unions, interest groups) and researchers (see Table 2). The interviews, lasting between 30 and 90 minutes, were conducted in person (n = 15), over the telephone (n = 25) and via email (n = 5) (Table 2). There were significant disparities between respondents on the basis of gender: only eleven women were interviewed compared to thirty-four men. It is generally acknowledged that there are currently fewer women in engineering and coastal management (Peers, 2018; Vila-Concejo et al., 2018), and it is possible that this is reflected in the low number of female respondents.

2.2.2 Thematic analysis framework and process

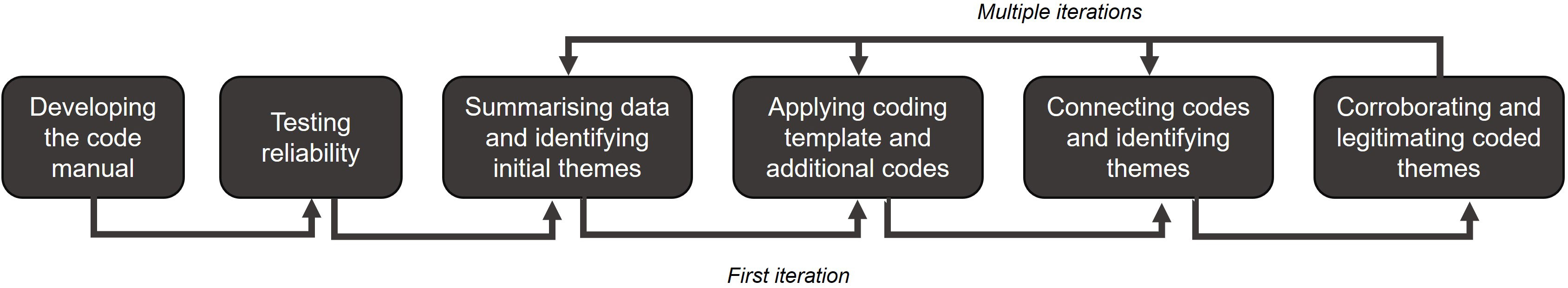

The interview data was analyzed through thematic analysis using an iterative process of theory- and data-based coding (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, 2006), and was carried out using NVIVO 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018) (Figure 2). First, a code manual of themes (description of a concept or phenomenon), categories (unit of organization that encompasses multiple codes) and codes (tags assigning units of meaning to the data) was constructed (DeCuir-Gunby et al., 2011; Saldaña, 2016). This code manual was based on (a) the seven themes identified by Tompkins et al. (2008) (costs, timing, power, responsibility, acceptability, equity and effectiveness) and; (b) a literature review and SWOT analysis on the challenges to integrating land use planning, engineering and insurance as coastal FRM in England (van der Plank et al., 2021). Following the testing of these codes with colleagues, a first round of coding was conducted using this first code manual as well as data-based coding (Saldaña, 2016). The code manual and themes were revised and tested, resulting in a code manual that combined the theory- and data-based codes of the first coding cycle – this manual was used for the second round of coding. From this coding cycle, a final series of themes, categories and codes was established.

Figure 2 Coding and thematic analysis method as outlined by Fereday and Muir-Cochrane (2006).

2.3 Statistical analysis of household perspectives of responsibility in FRM

2.3.1 Protection Motivation Theory framework

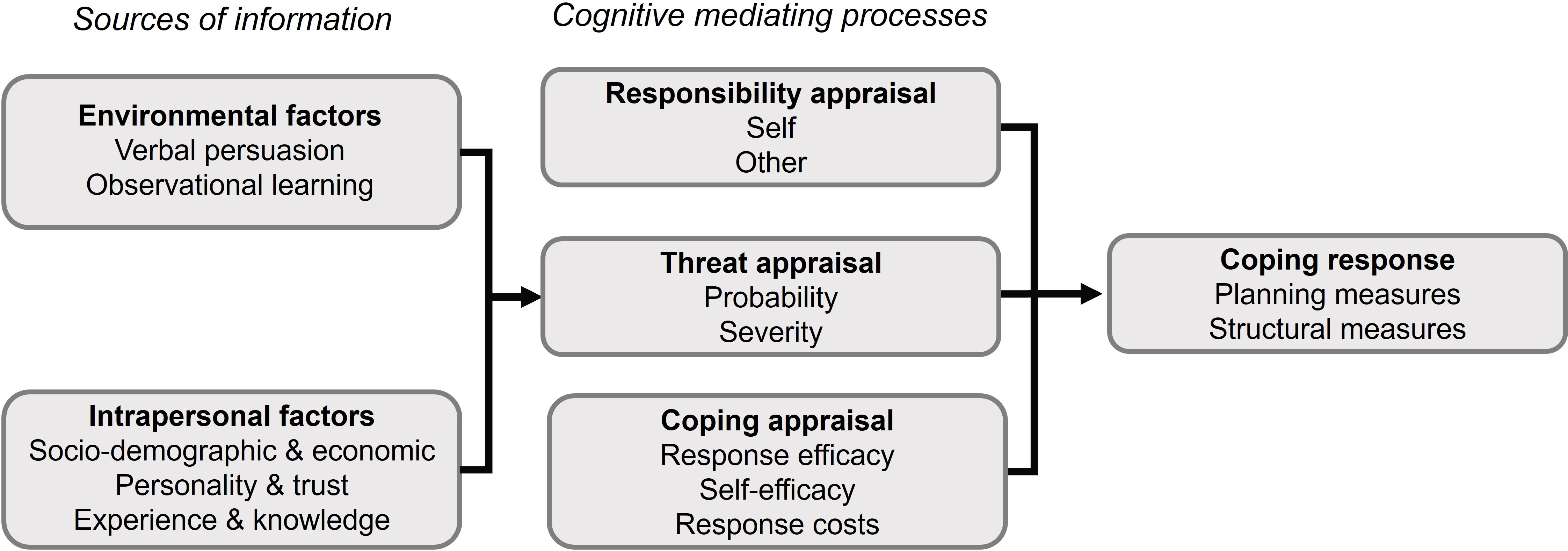

Our analysis builds on the widely used Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) to investigate the relationship between householder actions to adapt to coastal flood risk and their socio-economic characteristics, perceptions of flood risk, and adaptive capacity (Koerth et al., 2017). PMT was initially developed by Rogers (Rogers, 1975; Maddux and Rogers, 1983) to explain how individuals protect themselves against health risk, but is now also a widely accepted framework by which to study the protection motivation of householders against flood risk (Grothmann and Reusswig, 2006; Bubeck et al., 2013; Bamberg et al., 2017). PMT explains protection motivation and uptake of measures against a threat (or hazard) through the main cognitive processes people undergo when facing that particular threat. Originally, the main cognitive processes included were threat appraisal (how endangered someone feels by a risk) and coping appraisal (evaluating possible responses to the risk they face) (Bubeck et al., 2013). PMT has been extended to include further cognitive processes, as well as initial environmental and intrapersonal sources of information. Most notably for the purposes of this study, the work of Begg et al. (2017b), added responsibility appraisal (who is perceived to hold responsibilities in managing a risk) to the model. We focus especially on questions around perceived responsibility in coastal FRM to increase understanding of how responsibility and coping response are related (Mulilis and Duval, 1997; McLennan and Handmer, 2012). We use the model in Figure 3 to guide the survey development and analysis.

Figure 3 Protection Motivation Theory as applied in this study on household adaptation to coastal flood risk. Adapted from Bubeck et al. (2013). We measure the influence of sources of information and cognitive mediating processes directly on the uptake of coping response rather than motivation to protect, and especially focus on responsibility variables.

2.3.2 Household survey data collection

Due to limited extant data on protection motivation and action for coastal flooding in England, we used household surveys to collect PMT data for quantitative analysis (Bubeck et al., 2012; Bamberg et al., 2017; Bubeck et al., 2017). The survey included variables to test all key categories of the PMT model in Figure 3, namely: environmental and intrapersonal sources of information; threat, coping and responsibility appraisal; and coping responses, divided into structural measures (physical changes within the house) and planning measures (decision-making and information seeking actions) (see Supplementary Materials for full list of variables and survey questions). To test the clarity and inclusivity of the questions, the survey was pilot tested on colleagues and a revised version subsequently pre-tested on a small sample of households in Southampton prior to distribution in the north-east of England in July-August 2019.

Geographical criteria were used to inform the basic stratification of location and structure the random sampling (Koerth et al., 2013). The target population is residents in the case study area who are subject to a high level of coastal flood risk. To reduce sampling bias, postcodes were used as a sampling frame to obtain a random sample of these households in Flood Zone 3 (land with a >1% annual probability of river flooding or >0.5% annual probability of flooding from the sea). Within the randomly selected postcodes, every second residential dwelling was visited and one adult from each household was invited to participate. A total of 1,553 surveys were distributed, of which 26.1% were left behind in person, while 73.9% were left through the letterbox. The final sample was composed of 143 completed questionnaires (van der Plank, 2021), which is a typical return rate for self-return surveying (Terpstra, 2011; Poussin et al., 2015).

The survey responses were generally representative of the demographic profile of Lincolnshire. At 25%, the sample surveyed has a higher level of respondents holding a qualification of a degree level or higher than the Lincolnshire population (21%) (Lincolnshire Research Observatory, 2013). While 51.0% of respondents were aged over sixty-five compared to only 23% in Lincolnshire (in 2017) (Lincolnshire Research Observatory, 2018), individuals aged eighteen and below were excluded from the study, therefore increasing the expected average age of the sample. Most respondents (83.2%) were homeowners of either a flat or house (including bungalows), and 52.4% occupied a detached house. Respondents had been living in their current place of residence for an average of 19.2 years (Standard Deviation = 25.5) and had been resident in the area for an average of 33.8 years (SD = 25.5), indicating that respondents generally have a long affinity with the local area. Most households had no children living in their place of residence (85.3%), and the most common household size in the sample was two (57.3%). Of the 61% of respondents who provided income data, the most reported income bracket was £0–£12,748, falling below the Lincolnshire average of £18,754 in 2016 (Lincolnshire Research Observatory, 2016). Compared to a national population in 2011 made up of 51% women and 49% men, the survey captured slightly more male respondents, with 53.4% men and only 44.8% women (Office for National Statistics, 2018).

2.3.3 Survey analysis

The household survey data was analyzed using RStudio (R Core Team, 2019). Likert scales were used for the assessment of most items in the household survey pertaining to responsibility and adaptive capacity, although the measures of protection uptake by households were assessed through a count of the actions taken. For this study, the main analyses comprised descriptive analyses of responsibility variables, adaptive capacity variables and protection uptake variables, including the count, average (mean, mode and median), maximum and minimum, quartiles and measures of sample distribution. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used when investigating correlation between two sets of Likert-type questions, such as comparing perceptions of preparedness efficacy with perceptions of household responsibility.

3 Results

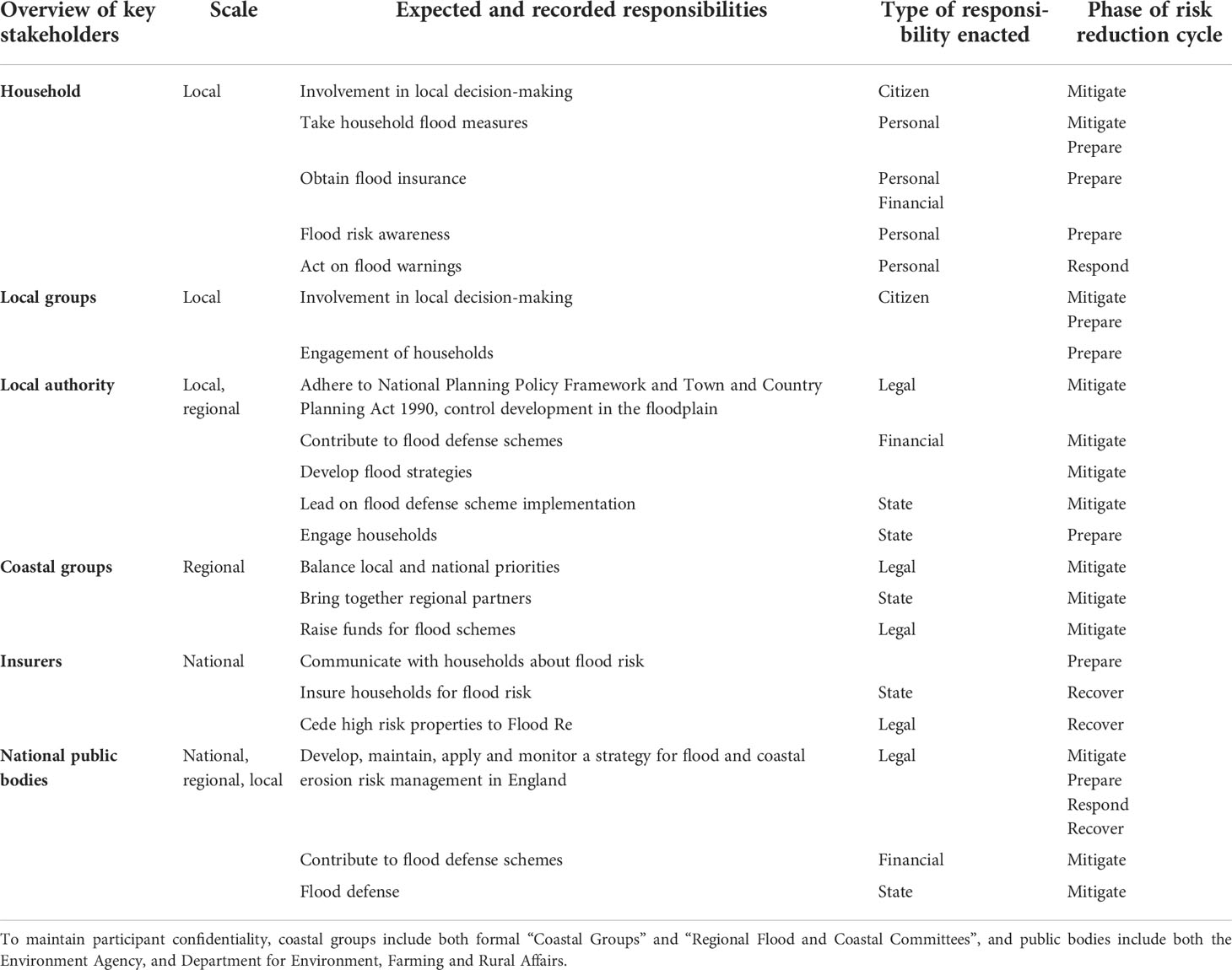

The data analysis demonstrates the variation in stakeholders’ perceptions of responsibility in policy and practices in coastal FRM, the lack of support that institutional stakeholders experience in engaging local stakeholders, and how householder perceptions of stakeholder responsibility are an important factor in their uptake of adaptation measures. We assess the discussion of institutional stakeholders pertaining to local involvement in coastal FRM, and the perceptions of households relating to their own and institutional stakeholder roles in coastal FRM, using the disaster risk reduction cycle to frame our analysis: risk mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery.

3.1 Risk mitigation and responsibility: engineered resistance as coastal flood risk adaptation endpoint

Engineered interventions to manage coastal flooding have a long history on the English coastline, for flood mitigation as well as for erosion (Charlier et al., 2005). As practitioners of one of multiple flood management approaches on the coast, engineers need to find effective ways to integrate their mitigation work with other sectors’ stakeholders, and this includes householders and other local stakeholders. However, we find that engineers are struggling to engage these groups in coastal flood risk mitigation processes; there was a perceived challenge of increasing people’s involvement in engaging with a risk that they may not experience for decades [17]. Further to this, limited resources hindered the stimulation of long-term public engagement in flood mitigation:

“The communication and engagement and the funding side, they’d be quite hard for a local authority on their own to justify one person, or afford even, one person” [19].

Further challenges include progressing beyond scheme-by-scheme FRM and better integrating non-hold-the-line options, i.e., alternatives or supplements to mitigation, into future adaptation. Numerous engineers called for a vision of managing the coastline beyond the scheme-by-scheme and mitigation defense-based approaches, such as one informed by community aspirations for their area with broad-minded solutions [5] [6] [7] [14] [19]. Yet the experience of interviewees is that the engineered mitigation actions such as the construction of flood defenses often remains the endpoint of planning and practice, with limited government and public dialogue about other options.

The dominance of the cost–benefit ratio in determining funding provision for flood defense schemes was noted in both the north-west and the south [13] [14] [15], as was the emphasis of funding calculations on the quantity of residential properties protected [14]. This focus limits the extent to which businesses and other assets are considered in calculations for estimating how much central government funding will support a proposed coastal FRM scheme. Cost–benefit analyses only capture the economic value of assets, and the current funding approach can inadvertently affect behavior so that “the funding policy drives a lot of behavior” [19]. Furthermore, outcomes of the calculations are not always followed because other influential factors take precedence, whether that be flood events or political pressure. One engineering consultant described how “Somebody worked in the Treasury who lived there, so it got protected” [5], while another outlined an instance in 2014 where

“Assets which were coming toward the end of their life in the plan and policy was to walk away, got rebuilt and upgraded to a higher standard than they were when the policy was set … there was pressure to rebuild them” [7].

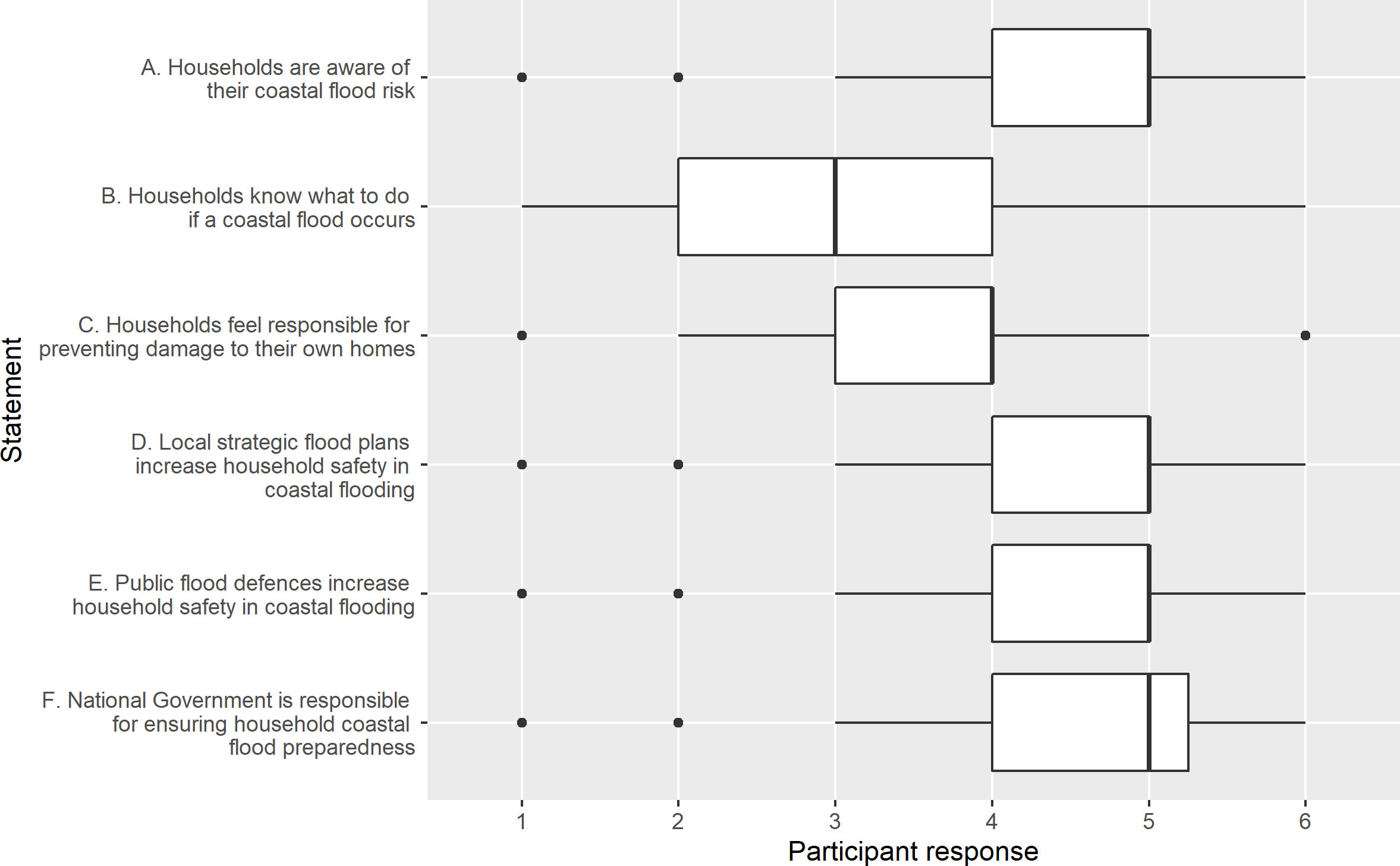

From a household perspective, we find that national government is strongly perceived to be responsible for mitigating coastal flood risk. The Likert findings are given in a one-to-six-point scale framework where low responses indicate disagreement with the statement, and high responses indicate agreement. The results in Figure 4 show that households are aware of multiple ways in which government actions are increasing safety regarding coastal flood risk, with a median of five regarding both perceived safety derived from local strategic flood plans and from flood defenses. Further, households generally perceive national government as responsible for ensuring household coastal flood preparedness (median value of five). Views on household awareness of coastal flood risk were also generally positive (median value of five). Nevertheless, householders were tending to negative perceptions regarding knowledge of what to do should flooding occur (median value of three). The median response for perceptions of household responsibility for preventing damage to their homes (Figure 4) was four, suggesting a slight tendency to perceive households as responsible – in contrast to the median of five regarding national government responsibility for household preparedness.

Figure 4 Household perceptions of coastal flood risk and responsibilities. Likert Scale: 1 represents strong disagreement with the statement, 3.5 represents a “neutral” stance, and 6 represents strong agreement with the statement. The median is represented by the central line. The horizontal extending lines show the total range, excluding data points more than 1.5 times the interquartile range away from the 25th and 75th percentile; these outliers are indicated as points.

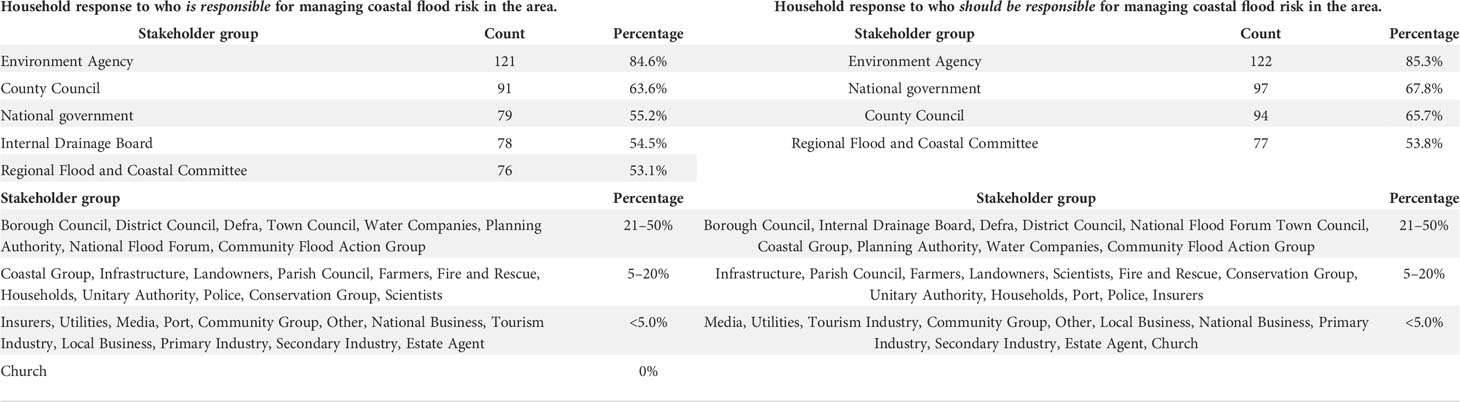

The perception of government agencies as responsible for coastal FRM overall was reiterated in responses to two questions where respondents could select multiple stakeholder groups who they thought are and should be responsible for coastal FRM (Table 3). Only twelve respondents thought households are responsible and only eleven thought they should be responsible. By contrast, public bodies were generally perceived both to be responsible and as those who should be responsible for managing coastal flood risk, namely, the EA, County Council, National Government, and Regional Flood and Coastal Committee – with over 50% of respondents indicating they perceived these stakeholders as being responsible. Notably, however, community flood action groups were indicated by 20-50% of respondents as being (and should be) responsible for coastal FRM, thus suggesting there is some perception of possible local group responsibilities for adaptation also.

Table 3 Household perceptions of responsible stakeholders: those who are and those who should be responsible for coastal flood risk management in their area.

3.2 Preparedness and responsibility: contrasting perceptions of household awareness and engagement in coastal flood risk adaptation

Many institutional stakeholders shared concerns about the lack of householders’ awareness and involvement in being prepared for coastal flooding. Respondents from various stakeholder groups spoke of the need for great household awareness of their role in flood preparedness.

“Encouraging people, businesses, families, communities to take greater responsibility for their own resilience … There tends to be an assumption that everyone is entitled to have public expenditure to protect them from flooding or erosion.” [2]

Engineering respondents, for example, argued that the public should be more attached, aware, responsible and involved in coastal FRM [5] [13] [16] [17]. Respondents from the insurance industry were similarly skeptical of public awareness of flood risk. One insurer described people as generally “myopic” and choosing “to stay ignorant” [11]. Somewhat in contrast to the idea that people are ignorant of their flood risk, a researcher described how, despite an expectation of government support, people still take out insurance to recover from flooding:

“I think there’s a lot of expectation, not just here but everywhere: OK, my house is flooded, the government will come … Then we have those insurances, which people pay to, maybe to get something back” [45].

Institutional stakeholders described the need to increase public awareness and engagement: “educating people to understand what’s happening, why it’s happening, and what the potential consequences are in the future” [25]. Respondents across case areas wanted an increased awareness among the public of the risk of coastal flooding; but raising awareness may not be solely about informing individuals of the possibility of coastal flooding. Stakeholders described the public as complacent:

“There’s lots of old families … who for generations have lived in the same house in the same street. And they say, ‘oh yes this [coastal flooding] happens’ … they couldn’t understand our concern.” [33]

Stakeholders spoke about the public needing to realize their own responsibility in managing flood risk, their ability to do something about it, and their expectation that government will resolve the issue [4] [5] [11] [39]. Interviewees pointed out the challenges of engaging communities who have not experienced a flood in many years and new owners as property changed hands [4] [8] [17]. Respondents were positive about engaging the public [1] [3] [15] [17] and wanted people to recognize their responsibility in coastal FRM: to be educated, to be prepared, to get involved with their coast, and/or to encourage each other to maintain drainage ditches [24] [25] [31] [44]. However, a local authority employee expressed concern that preparedness, for all of its merits, was overlooking some population groups; flood warnings, for example, would “miss out on a population of people who don’t have mobile phones” [21]. Thus, respondents were positive about engaging the public in coastal matters but were concerned about effects of legacy engineering work on people’s perceptions of their own exposure, and there was a call for increased engagement of households in coastal FRM.

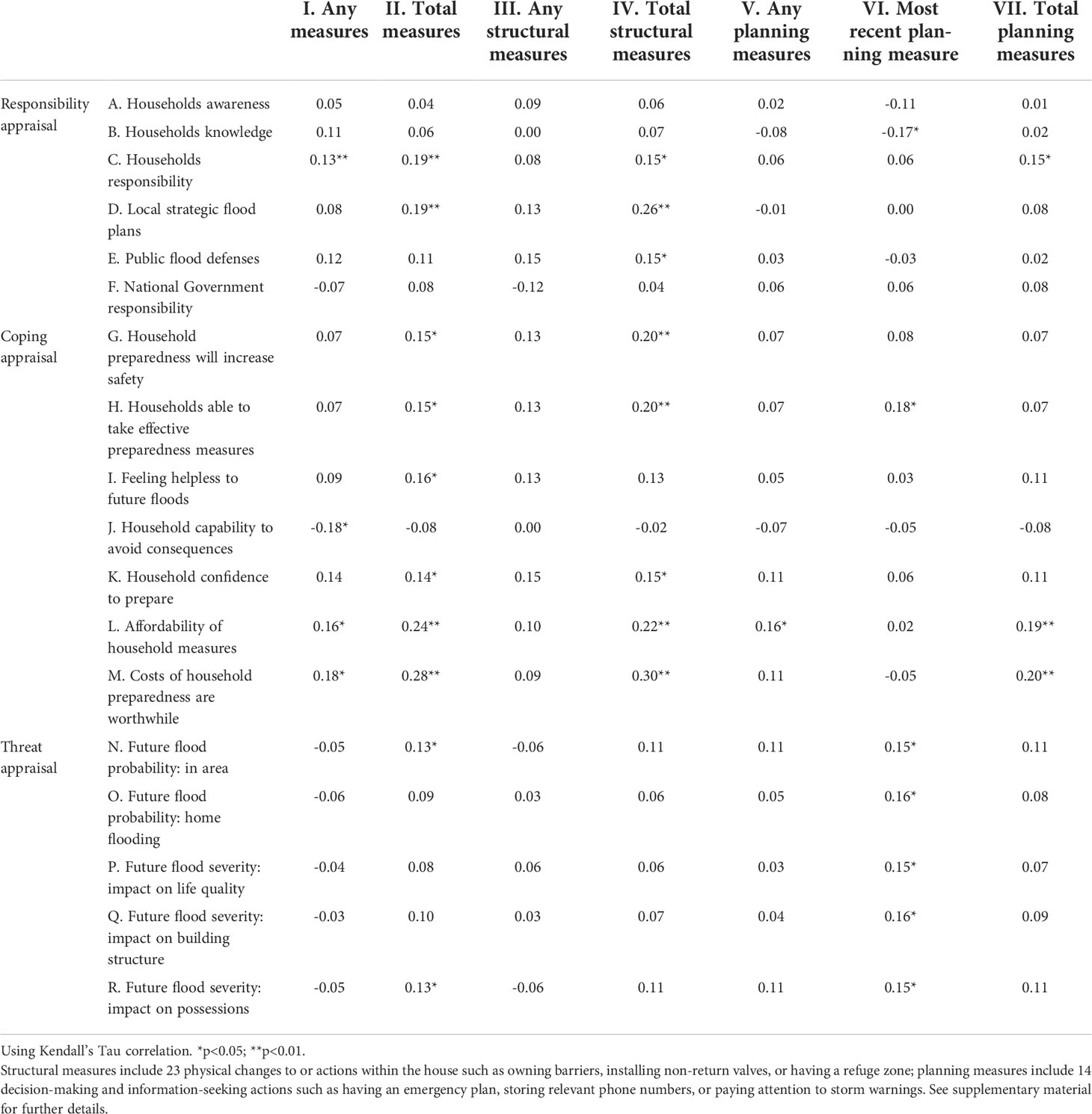

Table 4 depicts the correlations between householder perceptions of responsible stakeholders in coastal FRM generally (A-F) and of the uptake of household-level adaptation measures, encompassing whether any measures were taken (I), total measures taken (II), any structural measures taken (III), total structural measures taken (IV), any planning measures taken (V), how recently a planning measure was taken (VI), total planning measures taken (VII). Among the significant correlations (p <0.05) it is notable that householder with a stronger perceptions that households have a responsibility in coastal FRM were more likely to: take any measures (r = 0.13), take more measures in total (r = 0.19), take more structural measures in total (r = 0.15), and take more planning measures in total (r = 0.15). Knowing what to do related negatively to how recently a planning measure was taken (r = –0.17). Further factors related to uptake of structural measures include the perception of local strategic flood plans (r = 0.26) and perception of local flood defenses (r = 0.15). Perception of local strategic flood plans also correlated with the total measures taken (r = 0.19). Whilst the general effect of responsibility perceptions is therefore positive, both regarding household and other- responsibility, the negative influence of knowledge on timing of planning measures is concerning, we note the lack of effect of household coastal flood risk awareness or perceived national government responsibility on household adaptive measures.

Table 4 Correlations between appraisals of responsibility, coping and threat for coastal flood risk management, and uptake of adaptive measures by households.

Our primary focus is on the role of responsibility in household involvement in coastal FRM, but it is worth noting in Table 4 how a household’s appraisal of coping (perceived efficacy of response, perceived efficacy of self to adapt, and perceived costs of adaptation) and threat (perceived flood severity and likelihood) also correlate to uptake of adaptive measures. The results show that all three forms of coping appraisal (Table 4G- I, K-M) frequently correlate with the total number of measures taken (Table 4: II), as well as the total number of structural measures taken. By contrast, regarding threat appraisal only the perceived likelihood of the local area flooding and perceived impact of future floods on the household’s possession (Table 4: N, R) correlate with the total adaptation measures taken (Table 4: II), but all threat appraisal variables (Table 4: N-R) correlate positively with how recently a planning adaptation has been taken (Table 4: VI). This shows how responsibility has a more widespread correlation with adaptation, while in this case study the relationship of coping was limited largely to structural, and the relationship of threat was largely to the timing of planning measures.

3.3 Response and responsibility: resourcing household responsibility in coastal flood risk adaptation

Institutional stakeholders described their own responsibility to engage individuals and communities more in coastal FRM, such as in the context of flood events. The responsibility for household engagement was perceived as both an action on the part of households and institutional stakeholders. Four main areas of discussion around public awareness and engagement were raised. Namely, that the public: (1) should accept FRM decisions [6] [7], and (2) realize their own responsibility and agency [2] [7] [11] [33] [39], that there were (3) limits and challenges in the public taking action [4] [8], and (4) challenges for institutional stakeholders to engage the public [6] [7] [10] [13] [19]. There was recognition that the public has a preference in coastal FRM, not always for “a land of concrete” [17]. Limited resources for long-term engagement were raised as issues:

“Adaptation discussions require engagement, long-term engagement by probably someone local on the ground who can develop relationships. These people aren’t there. They don’t have the time and resources to invest in that level of engagement.” [7]

The majority of discussion related to resourcing and empowerment focused on the timing of funding, its sources and its dependence on defense-building. There was uncertainty of funding availability for long-term coastal FRM [6], and funding was perceived as more available directly in response to a flood event [12]. This post-flood event funding did not always adhere to longer-term plans:

“In practice, politicians step in and they say ‘it’ll never happen here again’ and then disproportionate amounts of money get siphoned off to … improvement of defenses.” [4]

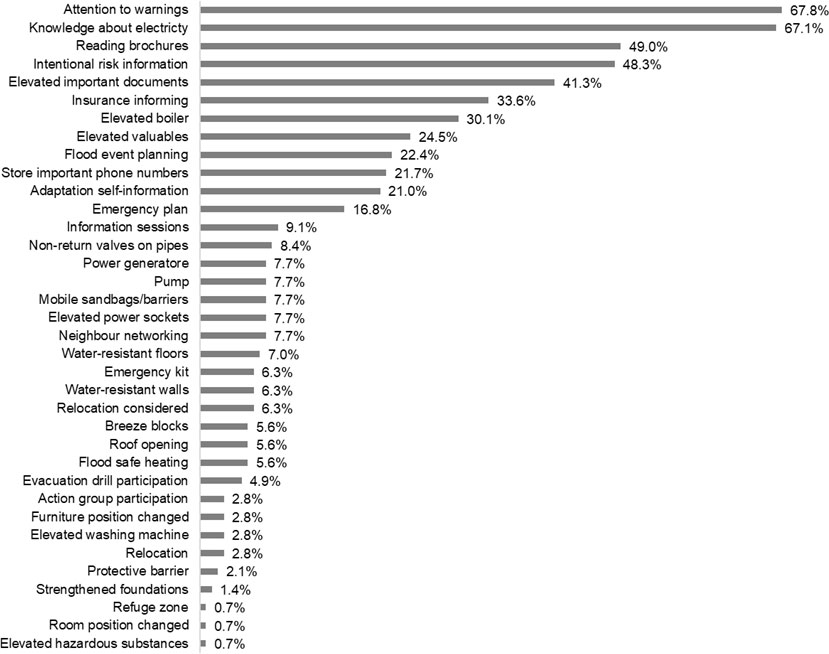

Households were asked about: (1) their uptake of twenty-three physical/structural actions (including an “other” option), and (2) how recently fourteen planning actions had been undertaken (plus an option to provide comments). Almost all households had undertaken at least one measure, at 94.4 per cent. The most common actions were: paying attention to storm warnings, knowing where to turn off electricity (structural), reading information brochures about flooding, seeking information about coastal flooding, and elevating important documents (structural) (Figure 5). The least common measures were: elevating hazardous substances, changing room positions within the household, having a refuge zone, and having strengthened foundations against flooding. The total number of implemented measures, out of the thirty-seven structural and planning options, ranged from zero to eighteen and on average, respondents took 6.6 measures (SD = 3.8). While most households have taken some form of adaptive action, the most common measures include those that are cheaper and lighter-touch, and may not be flood or hazard related – for example, knowing where to switch off electricity. Nevertheless, the high rate of attention for warnings (67.8%) and intentional seeking of information on coastal flood risk (48.3%) indicate personal awareness and interest in coastal flood risk.

Figure 5 Proportions of households (n = 143) who undertook specific structural and planning measures within all sample areas. Excludes “other” category. Respondents were also able to choose “Don’t Know” and “Prefer not to Say” for planning responses, or select no structural options.

3.4 Recovery and responsibility: engaging and accessing insurance for coastal flood risk adaptation

The insurance industry plays a critical role in the recovery stage of the disaster risk reduction cycle, offering, for example, not only the opportunity to build back but to “build back better” (UNISDR, 2017). Nevertheless, in discussions with institutional stakeholders, insurance was raised less often as an approach to managing coastal flood risk than planning or engineering, and one of the comments focused on its perceived absence from flood discussions:

“In my mind it’s the elephant in the room all the time … it’s quite interesting how little people talk about it, but how important it is. … A lot of it is - certainly some of the Partnership Funding policy and 300,000 homes is driven by the concern about insurability.” [19]

From discussions both with insurers as well as other key stakeholders, it becomes apparent that one of the biggest challenges for insurance as FRM is getting insurance involved in FRM in the first place. There is potentially a remnant of historical aversion to flood risk, because of its high costs: “It’s something that’s historically a pain in the backside to them” [10]. There was also a perceived distance between managers such as local authority engineers and insurers in managing coastal flood risk together [12] [19]. Timing of other FRM actions is critical in the effectiveness of insurance in the risk reduction cycle too. After severe flood events, government sometimes does offer flood grants for resistance and resilience measure uptake; however, this does not always time well with the insurance pay-out for household recovery [12]. Furthermore, similarly to other FRM approaches, “We [insurers] set ourselves up depending on the nature of the event” [12]; again, offering a window for cooperation which to date may not have been fully utilized by key stakeholders in FRM locally.

Beyond concerns around the absence of insurance in recovery, the potential – but currently perceived to be lacking – role for insurance in encouraging household and business flood resilience and resistance measurements was frequently raised. This was not described as currently being common practice because of: insurance policies not accounting for resilience measures [12], a lack of standards for and understanding of such measures [10]. However, one insurance respondent suggested this may be changing:

“There’s all this work going on at the minute to raise the awareness of that in the insurance market, get underwriters to understand the benefits of customers who’ve had flood resistance and flood resilience measures carried out.” [12]

It was suggested, nonetheless, that insurance not only play a recovery role but also prevents development today on the floodplain because one cannot access insurance: “People don’t build on floodplains because you can’t get insurance.” [19] Insurance therefore appears not only to play a recovery role in coastal FRM, but also a preventative role in reducing potential exposure. Further to this, one interviewee also described how having insurance and being aware of the risk are intertwined, thus reiterating the cyclical nature of flood risk reduction:

“I always say that insurance, whatever kind of insurance, awareness is the first step in managing any risk … Awareness of your flood risk is the first step into better managing it.” [10]

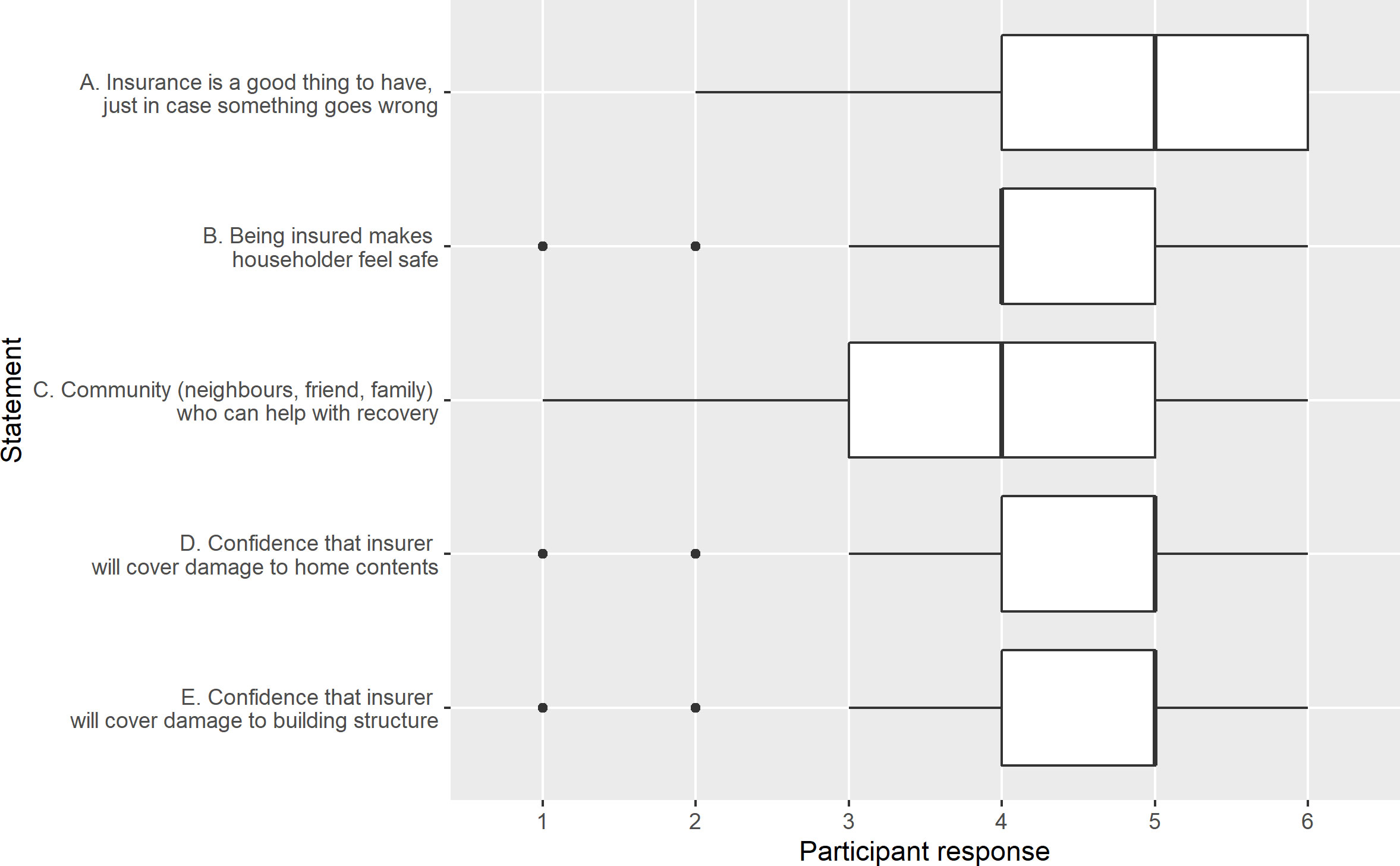

From a householder perspective, a critical pathway to recovery is through their capacity to access insurance (i.e., affordability), but also the perceived effectiveness of that insurance. On average, respondents exhibited high confidence in insurance as a pathway to recovery. In Figure 6, the average respondent was always positive about the role of insurance in coastal FRM, perceiving insurance as a good thing to have (A), and being confident that insurers would cover home contents and structural damages (D, E). Insurance made householders feel safe (B), and the average respondent also felt that they had a network who could support in flood event recovery (C). When householders were asked whether they had insurance, and whether insurers had encouraged them to take preparedness actions for coastal flooding, seventeen (11.9%) householders reported not having any form of household insurance and fifteen (10.5%) households did not respond. By far the largest group of respondents, 103 (72.0%), did have some form of insurance but had not received encouragement from their insurer in the past 10 years to prepare for coastal flooding. A much smaller group of eight (5.6%) participants had some form of insurance and had received encouragement from their insurer to prepare for coastal flooding. There appears to be high trust in insurers and their role in flood recovery, but the results suggest there is a lost opportunity for insurers to act on their relationship with households and encourage mitigation and preparedness actions in advance of flood events.

Figure 6 Household perceptions of insurance as a means to flood recovery. Likert Scale: 1 represents strong disagreement with the statement, 3.5 represents a “neutral” stance, and 6 represents strong agreement with the statement. The median is represented by the central line. The horizontal extending lines show the total range, excluding data points more than 1.5 times the interquartile range away from the 25th and 75th percentile; these outliers are indicated as points.

4 Discussion

In the European and broader international context, there has been an increasing research interest on the shifting distribution of responsibility in flood risk governance, specifically a devolution of responsibility toward local stakeholders and households (Begg, 2018; Thistlethwaite et al., 2020). There are concerns around poor support for communication and clarity in the allocation of responsibility, the need to increase capacity and information for household adaptation, and of the equity and effectiveness implications of expecting householders to be “flood risk citizens” or local stakeholders to hold significant FRM responsibilities (Nye et al., 2011; Elrick-Barr et al., 2016; Begg et al., 2017a; Thistlethwaite et al., 2020). When we do not know who is responsible what type of responsibility they hold, issues arise such as that now recognized around seaside landfills (Nicholls et al., 2021):

“A good example of risk that we do have a version of in the North West is landfill sites for rubbish which are on the coast. Where over time declining sea defenses might lead to breach, pollution issues, it’s not clear whose responsibility that would be because they’re closed sites and they don’t have operators. Again, there are versions of that all around the country.” [3]

In adaptation research a similar dialogue is ongoing, often warning against fully localized or private attribution of responsibility, concluding that despite private sector adaptations to climate change, the ultimate responsibility remains with the state (Schneider, 2014), or that devolving responsibility to local actors may be impeded by capacity constraints (Nalau et al., 2015). However, responsibility is often simplified to be between government and the “public” or individuals, as exemplified in the discussion in Muñoz-Duque et al. (2021) on risk perceptions of coastal flooding in Colombia, for example. Nevertheless, in this work we see a strong sense of state responsibility not being played out and also a challenge to enact civic responsibility because citizens lack trust in government, thus highlighting that in this system a reliance on civic and state responsibility for FRM may be problematic because of underlying problems with the relevant stakeholders to enact their responsibilities in the FRM cycle (Muñoz-Duque et al., 2021. Distinguishing between responsibility types and their roles in FRM systems may therefore enable identification of adaptation barriers and opportunities to overcoming them.

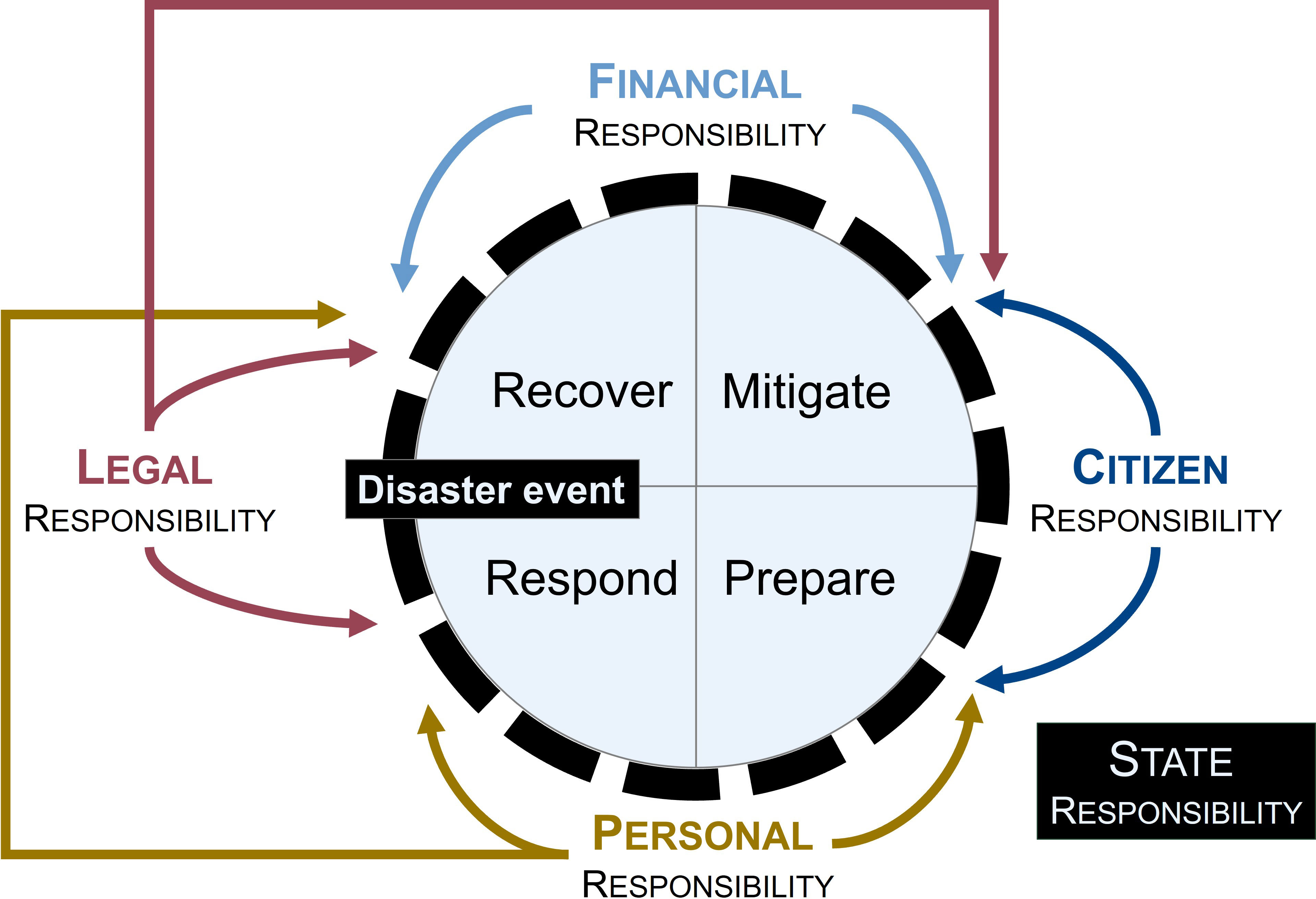

From our interviews with institutional stakeholders in England, and surveying of households, it is clear that there is not just one type of responsibility and that the differing forms of risk adaptation obligation likewise have varying forms of associated action and resource support. We therefore propose that there are five distinct forms of responsibility in adapting to changing coastal hazards, best characterized as: personal, financial, citizen, legal and state responsibility. Below, we expand on the definitions of each type, and propose a typology of responsibility in coastal adaptation.

4.1 Types of responsibility in coastal flood risk adaptation

4.1.1 Personal responsibility to be aware and prepared

In this empirical and past work, an increasing expectation has been observed for local stakeholders to play a role in managing risk, and for householders to be responsible stakeholders in adapting to flooding (Butler and Pidgeon, 2011; Begg et al., 2015). Recent policy statements suggest this is a continuing trend. In the quinquennial National Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Strategy for England released in 2020, the EA states:

“We all need to take action now so that we are ready for what the future will bring. Landowners, householders, businesses, insurers, emergency responders, environmental groups, community action groups, catchment partnerships, consultancies, regional flood and coastal committees, government agencies and many more, all have a vital part to play.” (p. 17)

In the same year, HM Government released a policy statement on Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management which similarly anticipates households taking property flood resilience measures to “manage the impact of flooding if it occurs” (p. 30). Nevertheless, the National Audit Office concluded in 2014 that further work was still needed in building engagement with the public around changes in flood defense standards (National Audit Office, 2014). In discussions with institutional stakeholders from the south and north-west of England, personal responsibility in the risk reduction cycle, especially in being prepared for flooding, was desired but not observed of households in relation to coastal FRM:

“The problem of managing flood risk is also encouraging people and businesses and communities to be ready for the risk of flooding if it does occur and to conduct themselves accordingly so as to minimize the damage to people and property.” [2]

This lack of progress in public engagement to increase household flood preparedness highlights how it is important to specify what is meant by household responsibility in coastal FRM. References to households remain vague in national policy, albeit suggestive that the expectation is for some level of individual acceptance and adaptation to risk to person (EA, 2020; HM Government, 2020). The survey results indicate that household awareness of flood risk is relatively high, but they are more likely to perceive other stakeholders such as the government to hold responsibilities in managing flood risk than themselves. Even if individuals and communities have a significant understanding of the risk, complicating factors in behavioral response to risk mean that understanding does not guarantee that preparedness, adaptation or management actions will ensue (Cologna et al., 2017). Nevertheless, we propose that this form of responsibility being intimated by contemporary English FRM policy is attempting to capture some form of personal responsibility – to be aware of, prepared and ready to protect oneself and one’s household from the risk of flooding.

4.1.2 Financial responsibility to bear the costs

The shift to expecting significant personal responsibility of householders is not the only observed transition in English FRM. The “Partnership Funding” scheme operational in funding FRM since 2011 represented a shift from dominant national funding to a system with a significant emphasis on third-party, often locally derived, funding (Thaler and Priest, 2014). In the latest National Audit Office (2020) report on FRM, partnership funding supported just over half (52%) of all schemes. Partnership funding may empower the additional contributors to have greater influence in scheme development, and it can enable schemes to go ahead that previously would not have acquired sufficient funding (Defra, 2011). In some cases, this may be achieved by partnerships between local authorities:

“Individual authorities struggle to get the funding themselves, to deliver a strategy on their own … they’ve all clubbed together … They’ve got all the authorities, they’ve got Network Rail, they’ve got the Environment Agency … Otherwise it wouldn’t be done because of the cost.” [1]

However, shifting the funding burden toward local, even household, contributions toward coastal FRM should be pursued with caution. Recent analysis has shown flood risks to be higher in socially vulnerable communities, especially in coastal areas and economically struggling cities (Sayers et al., 2018). Payment rates for protecting households in deprived areas are higher, but partnership funding does not account for the reduced spending capacity of economically struggling towns and households, nor for the possibly reduced social networks and social adaptation capacities of coastal communities (Lindley et al., 2011).

Nevertheless, this represents yet another movement of responsibility, namely that of financial responsibility for flood prevention, to the local level. Although partnership funding generally relies on institutional partners – the majority of partnership finance is still derived from the public sector (National Audit Office, 2020) – this is not a given, and some of the interviewees suggested that householders can have greater responsibility for risk in terms of funding more of their own FRM. Individuals are not only being expected by institutional stakeholders to take up attributed or increasing responsibilities for coastal FRM, but also to help finance it [4] [7]. One engineering consultant described cases where:

“Some private asset owners were trying to get government money … the eventual pushback was ‘no it’s your asset you pay for it,’ so private money had to be found.” [7]

Despite landowners and those behind defenses being encouraged to make funding contributions, Benson et al. (2016) suggest government maintains control of the structure of FRM processes, such as through the prioritization of specific flood defense objectives. This may mean, for example, that in areas where the long-term coastal planning document (or Shoreline Management Plan, “SMP”) suggests managed realignment or no active intervention in flood defenses, landowners may be mandated not to intervene physically in ongoing natural processes at all. What this discussion with stakeholders and within the literature highlights is that beyond the responsibility expected of households to keep themselves safe from flooding, there is now also some presumed financial contribution from local stakeholders to coastal FRM – a financial responsibility.

4.1.3 Citizen responsibility to be engaged in decision-making

Householders can influence coastal FRM in that they are citizens, i.e., as residents affected by processes of engagement and participatory decision-making (Blunkell, 2017; Pasquier et al., 2020; Puzyreva and de Vries, 2021). Despite a perceived lack of participation of the public in the case areas, multiple stakeholders suggested that the public should have a greater participatory role. Arnstein (1969) divides citizen empowerment into three degrees of involvement: the first offers little participation at all (non-participation), the second offer some tokenistic options (tokenism), and the third empowers citizens (citizen power). Taking the simple, widely cited model of Arnstein (1969) on the empowerment that participation offers the public, stakeholders’ description of the need to “educate” people about changing coastal flood risk resembles a tokenistic approach to participation, as opposed to supporting citizen empowerment. Public participation in hazard management therefore remains problematic: in terms of what level of participation is being offered to communities, and whether individuals within a community are equally represented in the participatory process (Few et al., 2007; Ianniello et al., 2019). One of the local group respondents in this study described their at-times tense relations with established coastal FRM stakeholders:

“We have an interesting relationship with the Environment Agency … As an organization, they just don’t seem to get what our issues and concerns are. Certain individuals within the hierarchy are just downright patronizing.” [24]

Knowing what the public thinks allows stakeholders to negotiate a shared responsibility for flood risk, and developing participation to be inclusive of individuals with different visions of flood management, regardless of their knowledge levels, has been previously suggested as a more inclusive and effective engagement practice (Birkholz et al., 2014; Smith and Bond, 2018). The EA uses a wide variety of public engagement approaches, including a flood warning service with 1.4 million people signed up, Regional Flood and Coastal Committees to work with coastal groups and lead local flood authorities, and regular campaigns to raise the awareness of households in flood risk areas (e.g., 2017–2018 campaign “Prepare, Act, Survive”). Nonetheless, the EA’s top-down approach in communicating flood risk has been previously highlighted (Nye et al., 2011), and these results suggest the “educating” focus perseveres in the two case areas.

These results imply that institutional stakeholders are perhaps only interested in tokenistic public participation in coastal adaptation, but that conclusion overlooks the barriers that institutional stakeholders themselves face in engaging the public in long-term coastal FRM. Despite the existence of long-term coastal strategy documents (i.e., SMPs), the short-termism of policy and funding alike was considered another limiting factor on longer-term and community co-developed coastal adaptation [6] [16] [17] [25]. Although the concept of managing flood risk rather than only seeking to reduce it is now widely accepted in policy and literature (Butler and Pidgeon, 2011; Dawson et al., 2011; Defra, 2011), the respondents call into doubt whether it also being politically and financially supported. Despite the call for more robust adaptation plans to future sea level rise and coastal change (CCC, 2018), interviewees described a lack of long-term engagement of the public in developing such plans in the case study areas. Thus, while there is an increasing national focus on long-term adaptation on the coast and on public responsibility for their resilience, stakeholders suggested this process is only just beginning at the local level. The desire to include households in long-term FRM planning indicates that there is another form of responsibility desired of householders – their responsibility as citizens, i.e., citizen responsibility.

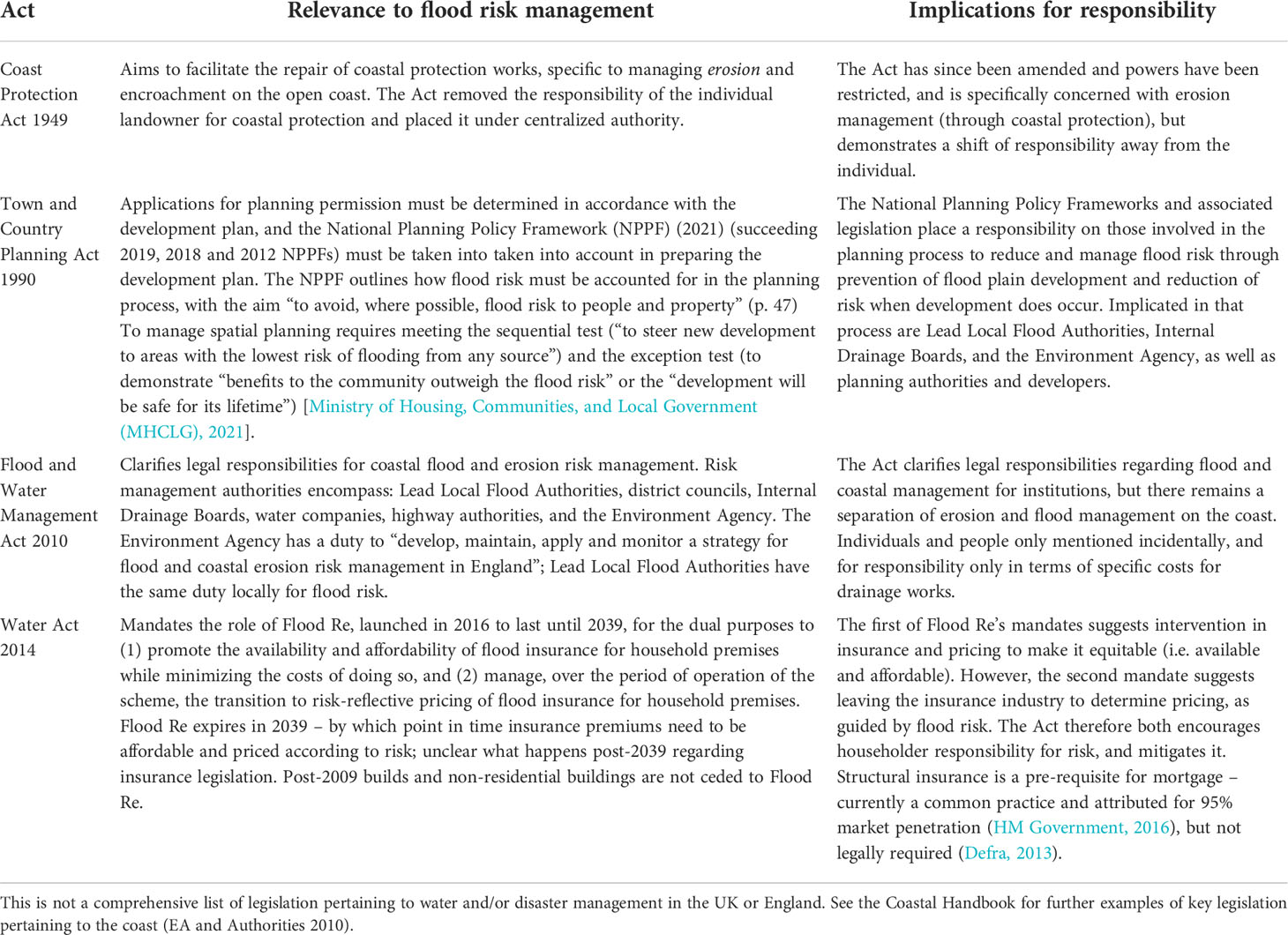

4.1.4 Legal responsibility to act within the scope of the law

The Coastal Handbook, a series of guidelines to support practitioners operating on the coast, lists nine acts, six directives, bye laws and legislation as relevant to the coast (EA and M.L. Authorities, 2010), and each identifies powers and requisite actions (responsibilities) of stakeholders. Legislation creates legally binding responsibilities as well as empowers stakeholders to enforce policy and carry out effective FRM practices. In Table 5, we capture some examples of coastal adaptation legislation and the implications for responsibility. Despite existing legislation on spatial planning for flood risk, the results show that legislation alone does not support planners as responsible stakeholders in coastal FRM. Engaging with planners was seen as challenging and coastal flood risk was considered to occupy little of planners’ focus. One local authority planner was positive about the role that evidence relating to coastal flood risk can play in long-term planning [26], but two other respondents expressed some concern at how much responsibility in flood risk planning for development has been placed on local authorities through legislation and policy changes in recent years [3] [15]. In some areas, planning outside of the floodplain is nigh impossible because of the prevalence of floodplain [25], and the coastal environment within which planners work is always changing as policy is updated and the coast is heavily used for recreation, homes and the economy [25] [26]. Stakeholders described how coastal strategy could be a higher priority for planners [1] [3] [25] [26] [38]. As one local authority planner explained:

“The National Planning Policy Framework … it doesn’t feel to me like they go far enough in terms of giving more weight to the consideration of flood risk issues … You can still build in the flood zone … National Policy should start from the position: you should not, must not, unless there are exceptional circumstances to build in Flood Zone 3.” [25]

Table 5 Examples of relevant UK/England legislation pertaining to flood risk and coastal management in chronological order, and the implications for flood risk management responsibilities.

Similarly to planning, national legislation explicitly mandates the role of the reinsurer Flood Re in making flood insurance both “affordable” and “risk-reflective” (Water Act 2014). Yet again, respondents characterized risk and resilience as being poorly understood by the insurance industry. Insurers remain hesitant to cover flood risk [10], and an insurer described one of the goals of Flood Re being to enable insurers to better understand the flood risk market [12]. Flood Re legislation and agreements could be interpreted to imply that everyone gets both defenses and insurance: “We have Flood Re … we would continue to offer affordable flood insurance … on condition that the government spent sufficient funds in flood defense infrastructure” [12]. That said, insurance and defense are now in a play-off against each other, as areas behind defenses that are currently being newly developed have the risk reduction from the defense but are not covered under Flood Re [19]. One public body employee reported having good contact with insurers [38], but an insurer suggested the opposite, stating that insurance remains distant from FRM [12].

The affordability of the Flood Re scheme has been achieved by linking maximum premium prices to the Council Tax band of the insured’s residential property. However, Council Tax bands differ considerably across England and are not per se proportional to disposable income (Davey, 2015). What may be an affordable price cap to insurance premiums in one region may not be so elsewhere. Climate change and increasing economic exposure threatens the future long-term affordability of flood insurance. Hudson et al. (2019) model the costs of risk-based flood insurance premiums in the European Union and estimate premiums could double between 2015 and 2055 in the absence of household risk reduction measures. Thus, the legal responsibility to provide access to affordable insurance is limited in effect when other responsibilities, such as of the state to the welfare of its people, are not also actioned in the delivery of flood insurance and protection.

Thus, despite the selected examples in Table 5 of the wider landscape of legal responsibilities in coastal FRM, the general conclusion drawn in this study is that legal responsibility alone does not establish clarity, supported and actionable responsibilities. Legal responsibilities are dependent on the development and support for other forms of responsibility also. This is exemplified in the context of Australia, where legally coastal protection falls under state and territory jurisdiction and is thereby the legal responsibility of eight different state and territorial legislative frameworks (Harvey, 2019). Most states, however, further delegate coastal management to local authorities, resulting in a plethora of policies, funding mechanisms and procedures, distinctions in strategy according to land ownership, and legal disputes arising from conflict between “common law rights of property owners to protect their land from erosion and the rights of the public for beach access and public amenity.” (Harvey, 2019) Legal responsibility in isolation, without consolidated and clear other forms of responsibility, may result in coastal management options being decided in court cases (Harvey, 2019).

4.1.5 State responsibility to the welfare of its citizens

This article adds to a literature on the shifting responsibilities in FRM and risk responsibilities more broadly (Johnson and Priest, 2008; Begg, 2018). Risk is long understood not solely to be composed of natural hazards, such as coastal flooding, but of social, economic and political components too – “vulnerability” (Blaikie et al., 2003). Whilst the practicalities of that responsibility shift may be observed in terms of financing, legislation and expectations of the citizen and the person (household), the overarching shift is one of the state’s responsibility for the welfare of its citizens and/or residents (Bickerstaff et al., 2008; Welsh, 2014).

The recognition of national government’s enduring and fundamental responsibility for risk is evident among householder responsibility perceptions, who not only (1) responded positively to the proposition that national government is responsible for ensuring households were prepared for coastal flooding (median of 5, mean of 4.4) (Figure 4), but also (2) 55.2% of household respondents selected national government as being responsible for coastal FRM and 67.8% thought that they should be responsible (Table 3). Government bodies, policies and legislation may be shifting the onus of responsibility to the local level (Johnson and Priest, 2008; Begg, 2018), but that practical shift does not necessitate a shift in citizen/resident perceptions of the welfare state’s fundamental responsibility to care. The social discourse that underpins coastal FRM was observed by the interviewees:

“It comes down to how informed the public is. If they choose to live there, they’re enjoying these fantastic views … the life that goes with living right on a coast, when it all comes to an end, is that not their problem, or does the state have some responsibility? It’s a difficult one. My view would be, I’d rather let people have the freedom to live there, but they must accept responsibility for what they’re doing, but that’s a social discussion.” [5]

In the English context, this primary responsibility has transformed through the twentieth and early twenty-first century but not necessarily been weakened. Twentieth and twenty-first century FRM in England has involved two broad movements, the first toward national governance, policy and financing, and the second toward devolved governance, increased local financing and systems-scale engineering (Butler and Pidgeon, 2011; Lumbroso and Vinet, 2011). Nevertheless, local stakeholders still look to national government for final guidance on how FRM should be carried out; and national government is held accountable when that guidance is not clear:

“They’re [Government] saying, “support communities”. But if you look at it in a different way, we’re saying, “we can’t support this, we can only support the relocation of this community”, or individuals. How you go about doing that, there is no real Government policy that allows you to do this? All the time we’re hitting up against what is written at a national level, when you come to actually think about the real consequences, there is a bit of a mess in national policy.” [6]

Research in both the fields of FRM and climate change adaptation have highlighted the mixed nature of responsibility in these management areas, with the public increasingly expected to take on responsibilities (Owusu et al., 2015; Klein et al., 2016). Yet the argument presented by Schneider (2014), that the ultimate responsibility to foster adaptation to climate change remains with the state, was supported by household perceptions data acquired in this research. Regardless of households’ perceptions of their own responsibility, they perceived government (EA, local authorities, national government) to also be responsible for coastal FRM. Nevertheless, individuals’ expectations of the state may differ per country in question; a study in the United States found, for example, that citizen perceptions and support for state flood mitigation work is negatively affected by its anticipated impacts on their property rights (Strother and Hatcher, 2021). Thus, clear state flood mitigation responsibility – as held by the Army Corps of Engineers at the federal level in the United States – does not necessitate public buy-in to proposed FRM.

This work identifies that clarity is lacking as to what both national policy and sub-national stakeholders are expecting of households, and that there is an urgent need to research and policy to clarify: (a) what households’ supposed responsibilities are within the risk reduction cycle for coastal flooding, (b) what capacity and support (finance, knowledge, confidence) they require to carry out those responsibilities, (c) how the expected adaptation responsibilities, or support therefore, will be distributed through a socially equitable process (Benzie, 2014; Nalau et al., 2015).

4.2 A proposed typology of responsibility for coastal flood disaster risk reduction

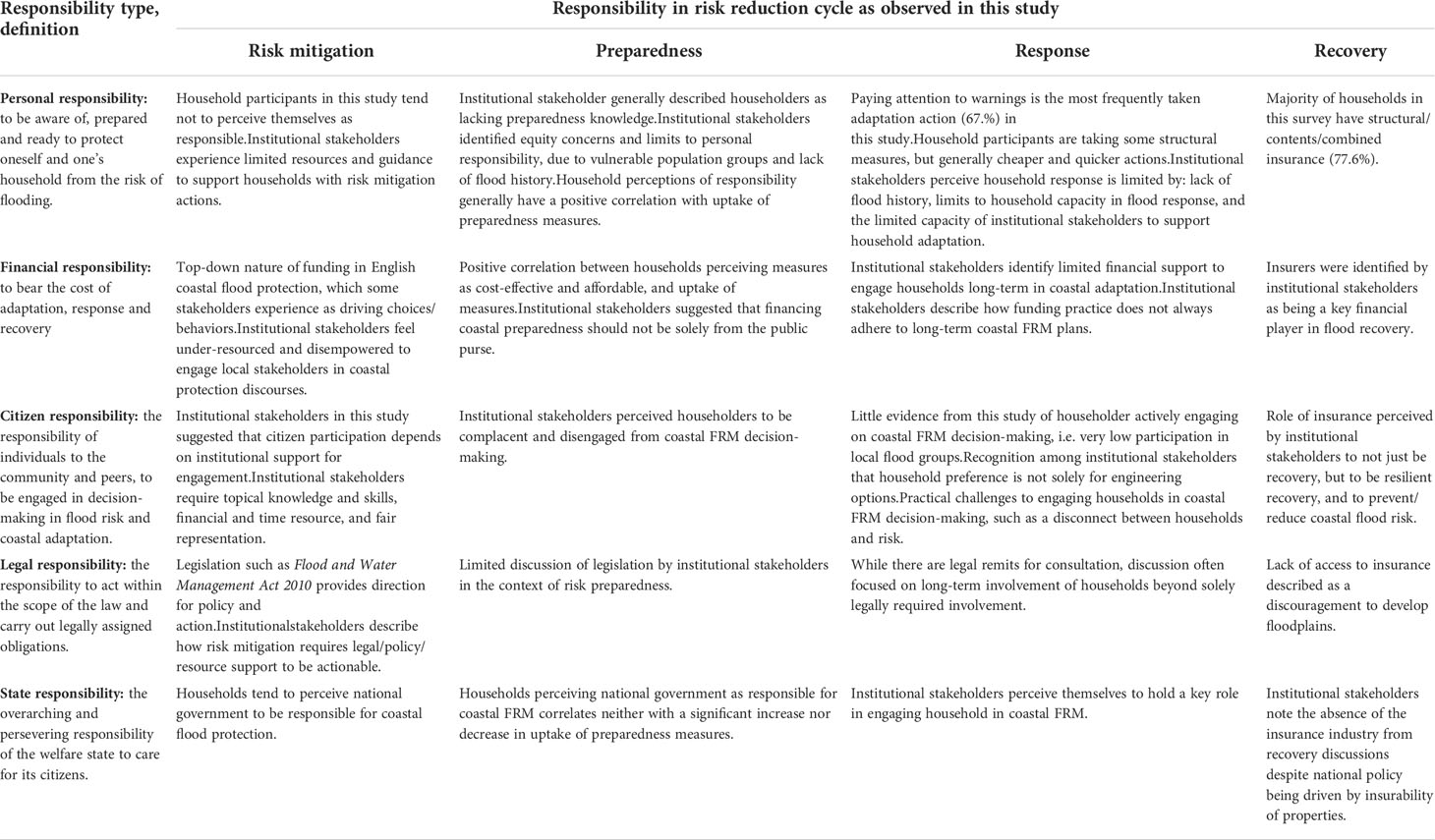

Responsibility is not simply a case of “us or them”, but shows itself to contain particularities regarding context. The shifting landscape of responsibility for specific actions within FRM in England and internationally has prompted discussions around affordability (Hudson, 2020), equality (Begg et al., 2015), effectiveness (Johnson and Priest, 2008), and accountability (Butler and Pidgeon, 2011), but largely missing from governance assessments of responsibility is a discussion on the differing types of responsibility, their characteristics and implications (Morrison et al., 2017). Across research, policy and practice there is therefore a lack of framework or structure by which to conceptualize questions that belong to the core of any hazard management or adaptation process – who should take action, why, how, where and when? And, as the institutional stakeholders’ experiences from this study relay, how are stakeholders responsible for a specific action supported by resources and training to enact their responsibilities? We bring together the five forms of responsibility identified in this work to form a typology of responsibilities in coastal adaptation, and explore the dominant ways in which each type of responsibility is enacted in the risk reduction cycle in the current English coastal flood risk context (Table 6).

Financial responsibility – the burden of costs, to pay for adaptation processes – is most often framed in terms of costs of mitigation and recovery practice. Placing this mitigation responsibility on households or on communities, as suggested by one interviewee (Table 6, [4]) raises equity issues in the English context where there is a higher likelihood of socio-economically vulnerable populations groups being exposed to coastal flood risk (Sayers et al., 2018). Placing this responsibility locally may render coastal FRM options unaffordable although, as Interviewee 1 describes (Table 6), the inability for one local authority to finance coastal FRM may encourage collaboration across authority boundaries, therefore also possibly reducing the effect of political boundaries on the management of a hazard that does not respect such boundaries (Lazarus et al., 2021).

Legal responsibilities – obligations prescribed in law – for coastal FRM are most prevalent across coastal flood response, recovery and mitigation. In the case of mitigation, the Flood and Water Management Act (2010) represented a clarifying moment for FRM responsibilities, with articulation of the division of responsibility between authorities (see Table 5). Nevertheless, this also results in political division of a geographical hazard, whereby management for coastal protection may become fragmented (Lazarus et al., 2021). Legal responsibility is also strongly present in disaster response and recovery processes, with legislation to protect life (Human Rights Act 1998 and Civil Contingencies Act 2004) and to aid local recovery (section 155 of the Local Government and Housing Act 1989).

Citizen responsibility – the obligations of residents to contribute to societies – is often described in holistic terms of engagement with the risk reduction cycle, but when specified relates mostly to mitigation and preparedness. To enact citizen responsibility through their participation (involvement, engagement) in the decision-making process requires topical knowledge and skills, financial and time resource, and fair representation. In the UK coastal adaptation context, despite a strong history of public participation, Blunkell (2017) argues that this support is not provided and falls short both of UK and United Nations aspirations for participatory decision-making. There are also concerns around participatory local decision-making in coastal adaptation accentuating existing socio-economic patterns of inequality (Begg et al., 2015).

The dialogue around personal responsibility – an individual’s onus to keep themselves safe – focuses mainly on the responsibility of households to be prepared for flooding, followed closely by a responsibility to take agency during response and recovery. Research continues to demonstrate that in policy and practice we are far from: ensuring that householders know how to take personal responsibility in the context to coastal hazards and flooding (Bubeck et al., 2012; Koerth et al., 2017) (Table 6, [7]), overcoming household scale adaptation constraints more generally (Berrang-Ford et al., 2021), and people’s willingness-to-pay being sufficient to afford the estimated costs of property-level flood measures (Kazmierczak and Bichard, 2010). When policy makers expect households to be personally responsible for managing their flood risk, they must also be mindful of the social-economic implications of expecting adaptation from groups whose adaptive capacity is likely to be lower than the general population (Sayers et al., 2018).

State responsibility is widely described in tangent with the risk reduction cycle as a whole. “Physical risks are always created and effected in social systems” (Beck 1992, p4) – in a welfare state, the state’s citizens environmental risks are composed not solely of the hazard, but of decisions which increase their exposure and vulnerability. In these case studies, the national government and government agencies (e.g. EA) were generally perceived both as being responsible and that they should be responsible for coastal FRM (Table 3). This sentiment of state responsibility was echoed by a local authority planner, who pointed out that increase use of the coastal zone has driven the rise of coastal flood risk on the “political agenda nationally” (Table 6, [26]). However, some interviewees thought that flooding did not rate highly enough on the government’s list of concerns, in that it is not perceived as a “major political issue”, and simultaneously not a major concern to the public (Table 6, [2]).

Whilst state, personal and citizen responsibilities may seem more directly linked to specific stakeholders – i.e., government and public bodies versus householders and individuals – what this research identifies and explains above is that even for these forms of responsibility to be clearly articulated, agreed and acted upon, requires cross-sectoral, cross-stakeholder discourse and policy, similarly to financial and legal responsibilities. In Table 7, we summarize key actions expected of various stakeholders in contemporary coastal FRM in England, and link these actions to the types of responsibility outlined in Table 6. For example, citizen responsibility cannot be effectively enacted without equitable, accessible and effective means for householders and individuals to engage in decision-making process; thus there are roles for public institutions to play in generating these conditions for citizen responsibility to be effected.