95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol. , 09 October 2017

Sec. Vaccines and Molecular Therapeutics

Volume 8 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01280

Antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections are difficult to treat, producing a burden on healthcare and the economy. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) strains frequently carry antibiotic resistance genes, cause infections outside of the intestine, and are causative agents of hospital-acquired infections. Developing a prevention strategy against this pathogen is challenging due to its antibiotic resistance and antigenic diversity. E. coli common pilus (ECP) is frequently found in ExPEC strains and may serve as a common antigen to induce protection against several ExPEC serotypes. In addition, live recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccine (RASV) strains have been used to prevent Salmonella infection and can also be modified to deliver foreign antigens. Thus, the objective of this study was to design a RASV to produce ECP on its surface and assess its ability to provide protection against ExPEC infections. To constitutively display ECP in a RASV strain, we genetically engineered a vector (pYA4428) containing aspartate-β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase and E. coli ecp genes and introduced it into RASV χ9558. RASV χ9558 containing an empty vector (pYA3337) was used as a control to assess protection conferred by the RASV strain without ECP. We assessed vaccine efficacy in in vitro bacterial inhibition assays and mouse models of ExPEC-associated human infections. We found that RASV χ9558(pYA4428) synthesized the major pilin (EcpA) and tip pilus adhesin (EcpD) on the bacterial surface. Mice orally vaccinated with RASV χ9558(pYA3337) without ECP or χ9558(pYA4428) with ECP, produced anti-Salmonella LPS and anti-E. coli EcpA and EcpD IgG and IgA antibodies. RASV strains showed protective potential against some E. coli and Salmonella strains as assessed using in vitro assays. In mouse sepsis and urinary tract infection challenge models, both vaccines had significant protection in some internal organs. Overall, this work showed that RASVs can elicit an immune response to E. coli and Salmonella antigens in some mice, provide significant protection in some internal organs during ExPEC challenge, and thus this study is a promising initial step toward developing a vaccine for prevention of ExPEC infections. Future studies should optimize the ExPEC antigens displayed by the RASV strain for a more robust immune response and enhanced protection against ExPEC infection.

Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) is a heterogeneous group of bacteria that causes extraintestinal diseases in humans and costs the US healthcare system over $1 billion annually (1). Human ExPEC strains can be subclassified into neonatal meningitis-causing E. coli, sepsis-associated E. coli, and uropathogenic E. coli that causes urinary tract infections (UTIs). In the US, ExPEC infections account for 17% of severe sepsis cases, are the primary cause of community-acquired UTI, and cause ~50% of nosocomial UTI (2, 3). Antibiotic-resistant ExPEC strains complicate treatment of these infections (4), but vaccination as an alternative to antibiotic treatment or a combined strategy against ExPEC may have a significant benefit to public health (5–7). Currently, no licensed vaccine exists for prevention of ExPEC in humans and those developed have lacked immunogenicity, safety, and cross-protectiveness (5).

Effective vaccine targets should be broadly protective against several ExPEC serotypes. E. coli common pilus (ECP) is an extracellular adhesin frequently present in E. coli and some other Enterobacteriaceae, e.g., Enterobacter cancerogenus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Serratia odorifera (8, 9). The ecpRABCDE operon encodes for a transcriptional regulator (EcpR), a major Pilin (EcpA), a putative chaperone (EcpB), an usher (EcpC), a tip pilus adhesin (EcpD), and a potential chaperone (EcpE) (8). In E. coli, ECP promotes biofilm formation on inert surfaces and contributes to colonization of human epithelial cell lines in vitro (8–13). Mutant ecp ExPEC strains have reduced ability to invade ex vivo mouse bladders (13). Virulence was also reduced in an avian pathogenic E. coli mutant ecp strain that had decreased ability to cause sepsis in chickens (10). Vaccination with ECP recombinant antigens was protective in a lethal mouse sepsis model (14). Additionally, ECP was produced in E. coli in urine samples from patients with UTI (13). These studies lend evidence that ECP may be a good vaccine antigen.

A vaccine that could provide protection against multiple pathogens would be highly desired considering its potential wide use and economic benefits. Antigen delivery by recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccine (RASV) strains has been used to induce immune responses against both the carrier Salmonella and foreign protective antigens from bacteria, viruses, and protozoa (15–20). RASVs can be delivered orally, which eliminates use of needles and syringes, and thus is an affordable choice for mass vaccination. Recently developed RASVs have the advantage of multiplying like wild-type organisms in the early phase of colonization and become avirulent following invasion into internal organs (15, 20). The objectives of this study were to (i) genetically engineer a RASV strain to synthesize and display E. coli EcpA and EcpD antigens; (ii) assess the ability of the RASV to elicit serum and mucosal immune responses in mice; (iii) evaluate the protective potential of the RASV against ExPEC and Salmonella using in vitro assays; and (iv) assess the RASV protective ability in animal models of ExPEC-associated human sepsis and UTI.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Arizona State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The protocol (#1168R) was approved by the Arizona State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Six-week-old female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) and 4-week-old female CBA/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were obtained for infection experiments. Mice were acclimated for 7 days before experiments began. During the experiments, animals were monitored twice daily by our team, animal caretakers, and further inspected by a veterinarian.

Strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. Strains were stored as stock cultures at −80°C in peptone-glycerol medium. Unless otherwise specified, strains were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) containing 0.1% glucose. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium attenuated strain χ9558, derived from the virulent S. Typhimurium strain UK-1 (χ3761), using strategies that enhance safety and immunogenicity (21, 22), was used to deliver ECP. Urosepsis strain CFT073 (23) was used in animal challenge experiments. ExPEC strains CFT073, JJ1886, UTI89, and RS218, non-pathogenic E. coli strains HS-4, J198, and Nissle 1917, laboratory E. coli MG1655, and S. Typhi χ3444, S. Typhimurium χ3761, and S. Paratyphi χ8387 strains were used for in vitro assays.

Recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains and challenge strain CFT073 were grown statically overnight in LB. The next day, the culture was inoculated 1:100 into fresh LB. RASV strains were grown with aeration at 37°C to OD600 of ~0.85. CFT073 was grown with aeration at 37°C to OD600 of ~0.85 (sepsis challenge) or statically overnight (intraurethral challenge). Strains were harvested by centrifugation at 24°C and resuspended in PBS.

Fragment ecpABCD, a 5622 bp portion of the ecp operon comprising ecpRABCDE, was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA of E. coli strain E24377A using KlenTaq LA DNA Polymerase (DNA Polymerase Technology, Inc., Saint Louis, MO, USA) and primer sets: P1: ecpA (BsrGI)-F: 5′ TAGTAATGTACATGAAAAAAAAGGTTCTGGCAATAG 3′ and P2: ecpD (HindIII)-R: 5′ CCCAAGCTTGGGTTAGTTAATGTTACGCCACCGTCGCC 3′ (Figure S1 in Supplementary Material). The amplified fragment included the 5′ region of the first gene, ecpA, from its start codon through the stop codon of the last gene, ecpD. To introduce the enzyme recognition site for BsrGI into vector pYA3337, we amplified the vector plasmid using primer sets: P3: pYA3337 (HindIII) F 5′ CCACAAGCTTGGCTGTTTTGGCGGATGAGA 3′ and P4: pYA3337 (BsrGI) R 5′ CCTATGTACATGTTTCCTGTGTGAAATTG 3′. The amplified fragment included at the 5′ region, the enzyme restriction site HindIII, and at the 3′ region, the enzyme restriction site BsrGI. PCR products were cloned into the pCR-XL-TOPO vector according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen).

PCR products of asd-positive vector pYA3337 (BsrG1-positive) and ecpABCD fragment cloned into the pCR-XL-TOPO were cut using HindIII and BsrGI enzymes, respectively. DNA bands of the digested ecpABCD(HindIII, BsrGI) and pYA3337(HindIII, BsrGI) were purified from an agarose gel and ligated together using T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) to generate plasmid pYA4428. Plasmids were verified by PCR, on agarose gel, restriction digestion analysis with HindIII and BsrGI, and sequencing.

The recombinant plasmid was first introduced into E. coli strain χ6212 commonly used for synthesis of foreign proteins (26). The purified plasmid obtained from χ6212 was then electroporated into competent cells of asd-negative Salmonella vaccine strain χ9558 to obtain the balanced-lethal construct. Selection for transformants was achieved by growth on LB agar plates and verified by PCR amplification.

Bacterial ECP synthesis was evaluated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot with rabbit anti-EcpA and -EcpD antibodies. The E. coli strain E24377A was used as a positive control and χ9558 containing ecpABC, ecpABCD, or ecpRABCDE were tested to determine which portion of the operon maintains ECP synthesis. χ9558 containing ecpABC or ecpRABCDE were constructed using the aforementioned methods. Surface display of ECP was visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using rabbit anti-EcpA and -EcpD antibodies and goat anti-rabbit IgG with 10 nm colloidal gold (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) at a concentration of 1:250 (9).

Mice were orally (behind the incisors) administered 20 µl using a pipette containing either PBS (unvaccinated), 109 CFU of χ9558(pYA3337) that carries the asd-plasmid with no ecp genes, or 109 CFU χ9558(pYA4428) that carries the asd-plasmid with ecpABCD (Figure S2 in Supplementary Material). Before immunization, mice were deprived of food and water for 4 h and resupplied 30 min after vaccination. Serum was obtained at days 20 and 41 (BALB/c mice) and days 20 and 30 (CBA/J mice) post-immunization from blood collected from the submandibular vein. Vaginal wash samples were obtained at days 28 and 41 (BALB/c mice) and day 28 (CBA/J mice) by repeated flushing of the vaginal tract and aspiration of 50 µl of PBS. Serum IgG and vaginal IgA and IgG responses against ECP proteins and Salmonella LPS were determined by ELISA as described previously (14). Briefly, E. coli antigens were PCR amplified and cloned into pET-101/D-TOPO vectors (Invitrogen) and expressed in E. coli strain BL21 as His-tagged proteins. Proteins were purified using ProBond Ni-NTA resin columns (Invitrogen). Endotoxin removal spin columns (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) were used to remove any remaining LPS from purified proteins. Commercial S. Typhimurium LPS (Sigma) was used as a source of LPS. Plates were coated at a concentration of 2.0 µg/ml of antigen and incubated overnight at 4°C. The remaining steps were performed at room temperature. Plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 and blocked for 1 h with SEA BLOCK (Thermo Scientific). Serum or vaginal wash samples were added at 1:50 or 1:10, respectively. Samples were diluted twofold down the plate, incubated for 1 h, and washed. Goat anti-mouse IgG for serum and day 41 vaginal wash samples from BALB/c mice (1:5,000; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) or goat anti-mouse IgA for all vaginal wash samples (1:5,000; Southern Biotech) was added and plates were incubated for 1 h. Plates were washed, and streptavidin, alkaline phosphatase conjugate (1:2,000; Southern Biotech) was added and incubated for 1 h. After incubation and washing, p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Thermo Scientific) was added according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The reaction was stopped with 2 N NaOH and plates were read at 405 nm. The endpoint titer was set as the reciprocal of the highest dilution that gave an OD405 twice that of the unvaccinated control.

Antibodies elicited against ECP were further evaluated by Western blot. Serum collected on day 41 was pooled in equal amounts from 10 mice per group. From unvaccinated, χ9558(pYA3337) and χ9558(pYA4428) immunized BALB/c mice pooled serum was used as a substitute for rabbit anti-EcpA to probe against purified EcpA by Western blot as described above.

Bacterial inhibition was tested using bacterial strains (Table 1) in pooled (n = 8/group, in equal volumes) serum or vaginal wash samples obtained on day 41 from BALB/c mice. Bacterial colonies from a fresh LB agar plate were suspended in M9 minimal media until OD600 reached 0.1. The suspension was diluted in M9 media (1 × 102 CFU), mixed with an equal volume of pooled serum or vaginal wash samples, and incubated at 37°C for 6 h. After incubation, the mixture was serially diluted and plated on MacConkey agar to determine viable counts. Samples were tested in duplicate in two independent experiments.

Mouse models of human sepsis and UTI were used to evaluate the protective ability of RASV immunization. For the mouse sepsis model, BALB/c mice were intraperitoneally challenged with 100 µl of PBS containing 108 CFU of CFT073 on day 41 postvaccination. Previously, 100% lethality was observed in a mouse sepsis model using 108 CFU of CFT073 by 7 days postchallenge (34). In order to quantitatively determine bacterial loads in internal organs, previous studies have used early endpoints of 24–48 h postchallenge with CFT073 (35, 36). Therefore, mice were euthanized before lethality at 24 h postchallenge, and blood, liver, and spleen were collected, serially diluted, and plated on MacConkey agar for enumeration of E. coli.

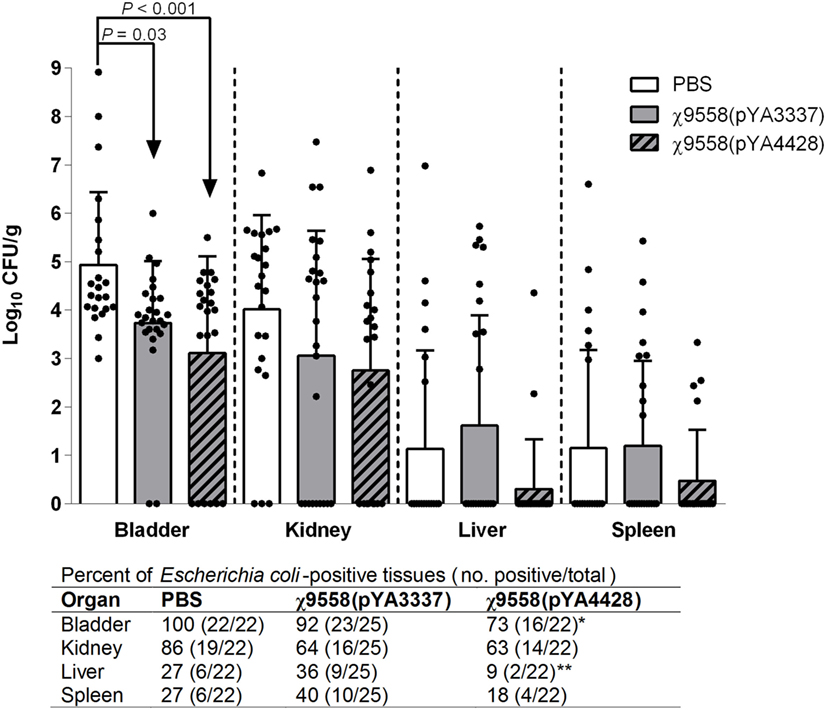

For the mouse UTI model, CBA/J mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized with a cocktail of ketamine (100 mg/kg), xylazine (10 mg/kg), and acepromazine (2.5 mg/kg) and the bladder was emptied by gentle pressure on the abdomen. The median infection dose for transurethral inoculation of CFT073 was determined previously as 106 CFU/mouse (35). To ensure infection, mice were inoculated with 50 µl of PBS containing 108 CFU of CFT073 via transurethral catheterization using a sterile polyethylene catheter (Intramedic, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) on day 28 postvaccination. At 48 h postchallenge, mice were euthanized and bladder, kidney, liver, and spleen samples were collected, serially diluted, and plated on MacConkey agar for enumeration of E. coli.

An ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons was used to compare between groups for ELISAs, in vitro sera and vaginal wash assays, and the sepsis and UTI models. Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used to compare treatments for the proportion of tissues positive for E. coli in the UTI mouse model. Analyses were carried out in GraphPad Prism 6.0. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

As screened on the SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie blue and Western blot (Figure S3 in Supplementary Material), ECP production was detected in χ9558(pYA4428) but not in χ9558(pYA3337). EcpA and EcpD were displayed on the surface of χ9558(pYA4428) as shown by TEM (Figure S4 in Supplementary Material).

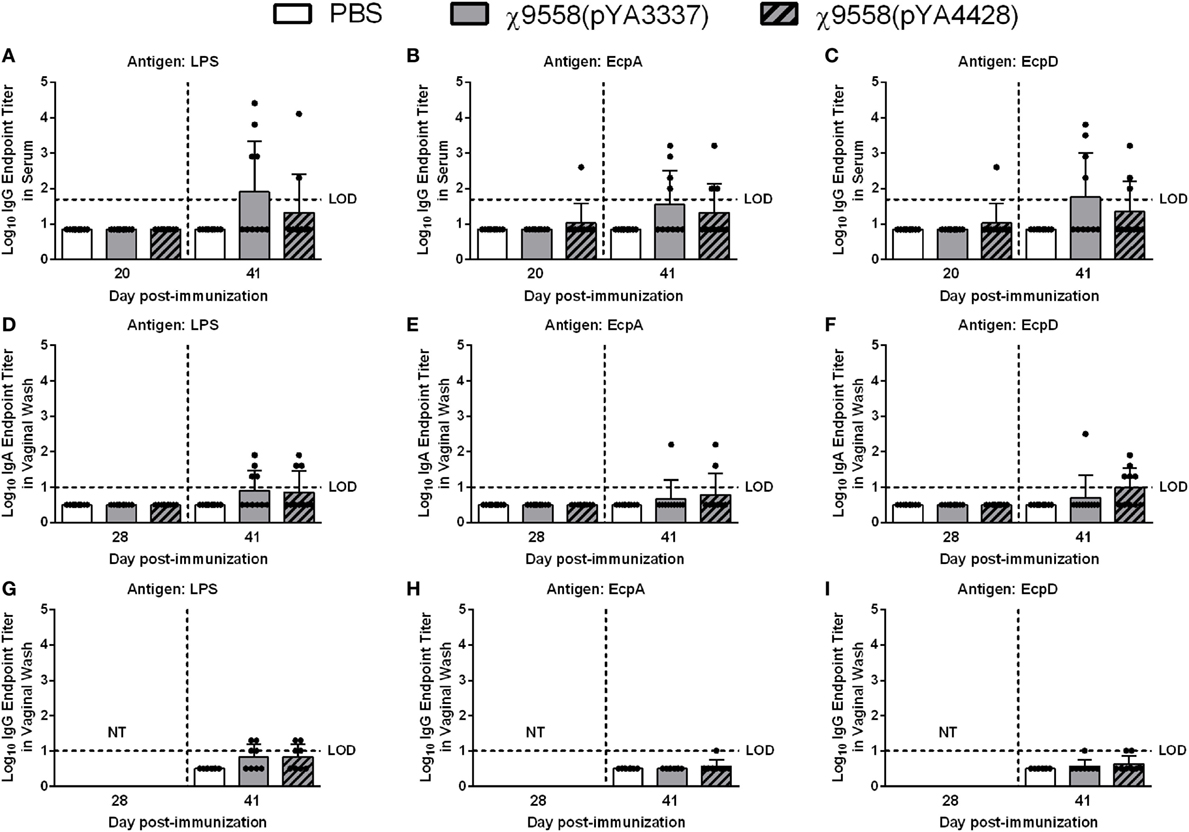

To assess immune responses to vaccination, serum and vaginal wash samples from 8 to 10 individual mice per treatment were evaluated by ELISA for anti-Salmonella LPS and anti-E. coli (EcpA and EcpD) antibodies. For BALB/c mice on day 20, only one mouse vaccinated with χ9558(pYA4428) elicited anti-EcpA and EcpD IgG antibodies, and no IgG antibodies were observed for LPS (Figure 1). On day 28, no IgA antibodies were detected in vaginal wash samples or if elicited were below the limit of detection in the ELISA. On day 41, some mice vaccinated with χ9558(pYA3337) or χ9558(pYA4428) elicited IgG and IgA antibodies to all three antigens, except that no IgG antibodies were detected against EcpA from vaginal wash samples of χ9558(pYA3337) immunized mice. Although some RASV immunized mice had elevated antibody titers compared with unvaccinated mice, no significant differences were observed between vaccinated and unvaccinated mice or between vaccination groups.

Figure 1. Antibody responses against Salmonella LPS and Escherichia coli common pilus antigens in vaccinated BALB/c mice. Data represent (A–C) serum IgG (D–F) vaginal wash IgA, and (G–I) vaginal wash IgG antibody levels induced in BALB/c mice immunized with PBS, χ9558(pYA3337), or χ9558(pYA4428). Individual samples from 8 to 10 mice per treatment were analyzed by ELISA against Salmonella LPS and E. coli EcpA and EcpD. Day 28 vaginal wash samples were not tested (NT) for IgG. Bars represent the mean and each dot represents an individual mouse. The horizontal dashed line represents the limit of detection (LOD). Samples that tested negative were assigned a value halfway between zero and the LOD. Error bars represent SDs.

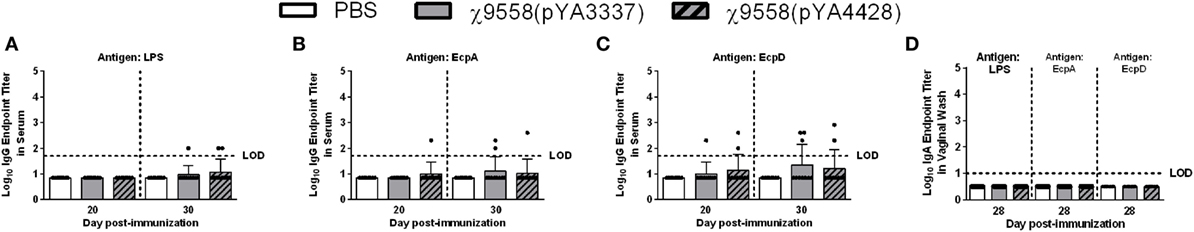

For CBA/J mice on day 20, serum and vaginal wash samples from ten individual mice per group were tested by ELISA. Only one χ9558(pYA4428) vaccinated mouse but not χ9558(pYA3337), elicited anti-EcpA IgG antibodies, one χ9558(pYA3337) and two χ9558(pYA4428) immunized mice elicited anti-EcpD IgG antibodies, and no anti-LPS IgG antibodies were observed (Figure 2). Similar to unvaccinated mice, anti-LPS, anti-EcpA, and anti-EcpD IgA antibodies were not detected in vaginal washes of vaccinated mice on day 28. On day 30, one χ9558(pYA3337) and two χ9558(pYA4428) immunized mice elicited anti-LPS IgG antibodies, two χ9558(pYA3337) and one χ9558(pYA4428) immunized mice elicited anti-EcpA IgG antibodies, and three χ9558(pYA3337) and two χ9558(pYA4428) immunized mice elicited anti-EcpD IgG antibodies.

Figure 2. Antibody responses against Salmonella LPS and Escherichia coli common pilus antigens in vaccinated CBA/J mice. Data represent (A–C) serum IgG and (D) vaginal wash IgA antibody levels induced in CBA/J mice immunized with PBS, χ9558(pYA3337), or χ9558(pYA4428). Individual samples from 10 mice per treatment were analyzed by ELISA against Salmonella LPS and E. coli EcpA and EcpD. Bars represent the mean and each dot represents an individual mouse. The horizontal dashed line represents the limit of detection (LOD). Samples that tested negative were assigned a value halfway between zero and the LOD. Error bars represent SDs.

To determine whether antibodies against ECP were also detected by Western blot, pooled serum collected from BALB/c mice (n = 10/group) was used to probe purified EcpA. Western blot analysis showed no reaction to purified EcpA when probed with serum extracted from unvaccinated or χ9558(pYA3337) immunized mice (Figure S5 in Supplementary Material). A positive reaction was observed for serum from χ9558(pYA4428) immunized mice. Thus, we confirmed our ELISA results for χ9558(pYA4428) but could not confirm our results for χ9558(pYA3337) by Western blot.

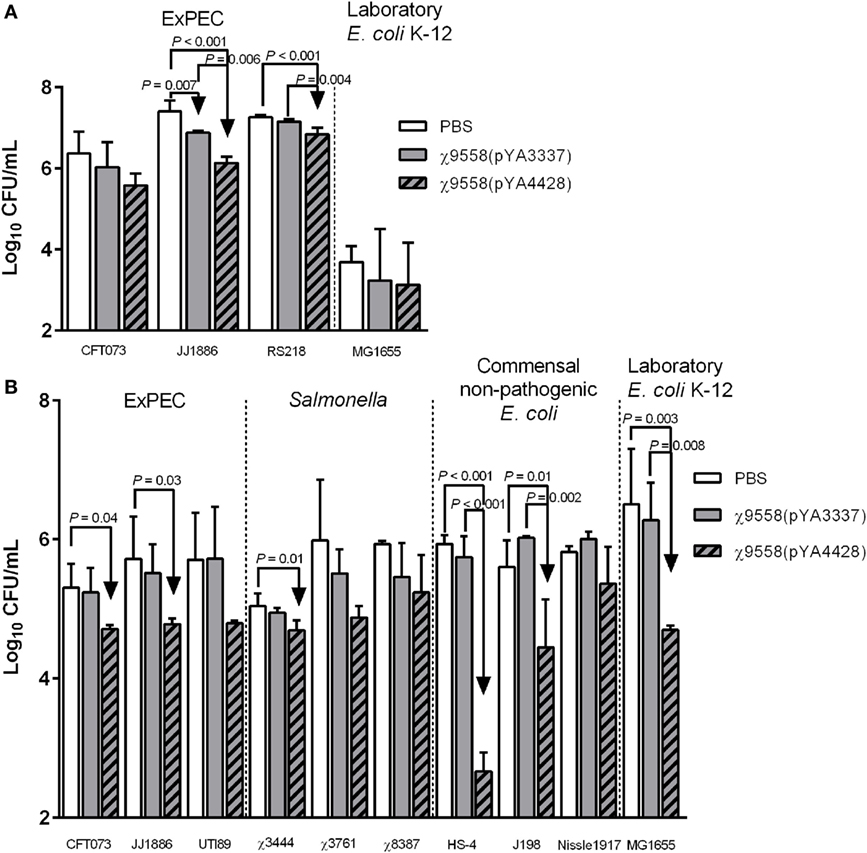

Pooled mouse serum and vaginal wash samples from 10 mice by group were mixed with bacterial strains and incubated for 6 h to determine whether antibodies or other antimicrobial products elicited from RASV immunization influenced bacterial levels. These assays were used to test inhibitory activity of serum and vaginal wash samples against multiple pathogenic bacterial strains including ExPEC and Salmonella strains not tested in vivo and non-pathogenic E. coli strains that represent organisms inherent in the gastrointestinal tract of humans. A limited amount of sera was collected during the study, and therefore, heat-inactivation of sera was not used as a control. Generally, sera from mice vaccinated with χ9558(pYA4428) had the strongest inhibition against strains (Figure 3). The urosepsis strain JJ1886 was significantly decreased in serum samples of both χ9558(pYA3337) and χ9558(pYA4428) vaccinated mice compared with unvaccinated mice (Figure 3A). A significant decrease was also observed in serum of χ9558(pYA4428) compared with χ9558(pYA3337) immunized mice. The neonatal meningitis-causing E. coli strain RS218 was significantly decreased in serum from χ9558(pYA4428) immunized mice but not χ9558(pYA3337) compared with unvaccinated mice. A significant decrease in levels of RS218 was detected in serum of χ9558(pYA4428) compared with that of χ9558(pYA3337) immunized mice. No significant differences were observed for urosepsis strain CFT073 or laboratory E. coli strain MG1655 between treatments.

Figure 3. Bacterial inhibition of serum and vaginal wash samples from BALB/c mice. (A) Serum or (B) vaginal wash samples were mixed 1:1 with bacterial strain cultures and incubated at 37°C for 6 h. After incubation, mixtures were plated on MacConkey agar for bacterial enumerations. Bacterial levels between groups were compared by an ANOVA followed by Tukey’s method for multiple comparisons. P values <0.05 were considered significant. Error bars represent SDs.

Cervicovaginal lavage samples from healthy women have been shown to inhibit growth of E. coli ex vivo (37). To determine if RASV immunization influences bacterial inhibition, various ExPEC, Salmonella, and non-pathogenic E. coli strains were tested for growth in vaginal wash samples (Figure 3B). Two of three ExPEC strains (CFT073 and JJ1886) were significantly reduced in vaginal washes from χ9558(pYA4428) immunized mice but not χ9558(pYA3337) compared to unvaccinated mice. One of three Salmonella strains (S. Typhi χ3444), two of three commensal non-pathogenic E. coli strains (HS-4 and J198), and laboratory E. coli strain MG1655 had significantly decreased levels in vaginal washes from χ9558(pYA4428) vaccinated mice but not in that of χ9558(pYA3337) compared to unvaccinated mice. No significant differences were detected between χ9558(pYA3337) vaccinated and unvaccinated mice or between any of the treatments for ExPEC strain UTI89, S. Typhimurium χ3761, S. Paratyphi χ8387, and E. coli Nissle 1917.

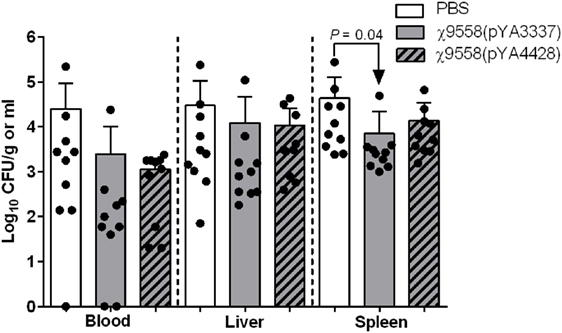

After vaccination, all mice survived and no clinical signs of disease due to Salmonella infection (diarrhea, weight loss, etc.) were observed. In the mouse model of sepsis, BALB/c mice were intraperitoneally challenged with 108 CFU of CFT073 to assess the efficacy of vaccine treatment against systemic infection. BALB/c mice were selected based on past sepsis studies using this genetic background to evaluate ExPEC vaccines (36, 38). The only significant difference relating to bacterial loads in the mouse sepsis model was in the spleen of mice vaccinated with χ9558(pYA3337) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect of vaccination on extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strain CFT073 ability to cause sepsis in mice. Female BALB/c mice were immunized with PBS, χ9558(pYA3337), or χ9558(pYA4428), challenged intraperitoneally with 108 CFU of CFT073, and assessed 24 h postchallenge for bacterial concentration in the blood, liver, and spleen. Each experimental group contained 10 mice. Each dot represents an individual mouse and vertical dashed lines separate sample type. Bacterial loads of mice between groups were compared by an ANOVA followed by Tukey’s method for multiple comparisons. P values <0.05 were considered significant. Error bars represent SDs.

In the UTI mouse model, CBA/J mice were intraurethrally challenged with 108 CFU of CFT073 to determine the impact of vaccination on bacterial loads in urinary system organs (bladder and kidney) and other internal organs (liver and spleen) (Figure 5). CBA/J mice were selected based on an established UTI protocol (39) to assess the efficacy of vaccine treatment against UTI, and to assess whether a different genetic background resulted in a response similar to RASV immunization of BALB/c mice. In general, mice vaccinated with RASV strains had numerically lower bacterial loads in organs. Significantly lower bacterial loads than unvaccinated mice were observed in the bladder for both χ9558(pYA3337) and χ9558(pYA4428). Also, χ9558(pYA4428) but not χ9558(pYA3337) vaccinated mice had significantly fewer number of E. coli-positive bladder samples than unvaccinated mice. In the kidney, liver, and spleen, bacterial loads for both χ9558(pYA3337) and χ9558(pYA4428) were not significantly different than unvaccinated mice. However, for the liver, χ9558(pYA4428) vaccinated mice had significantly fewer number of E. coli-positive samples than χ9558(pYA3337), but was not significantly different from unvaccinated mice.

Figure 5. Effect of vaccination on extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strain CFT073 ability to cause urinary tract infection in mice. Female CBA/J mice were immunized with PBS, χ9558(pYA3337), or χ9558(pYA4428), challenged intraurethrally with 108 CFU of CFT073, and assessed 48 h postchallenge for bacterial concentration in the bladder, kidney, liver, and spleen. Each experimental group contained at least 22 mice. Each dot represents an individual mouse and vertical dashed lines separate tissue type. Bacterial loads between groups were compared by an ANOVA followed by Tukey’s method for multiple comparisons. Below the x-axis for the number of E. coli-positive tissues, an asterisk (*) represents a significant (P < 0.05) difference for a vaccine treatment compared with the unvaccinated treatment, and two asterisks (**) represents a significant (P < 0.05) difference for χ9558(pYA4428) compared with χ9558(pYA3337) immunization as determined by Fisher’s exact test. Error bars represent SDs.

Recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains colonize the intestinal mucosa and other lymphoid tissues to elicit mucosal and systemic immunity, which is important for protection against an invasive pathogen like ExPEC (40). Previously, RASV χ9558 delivering a pneumococcal antigen replicated and colonized the Peyer’s patches, spleen, and liver of mice for at least 3 weeks post-vaccination (41). Also, as used in the current study, RASV strains with a regulated delayed lysis in vivo system colonize the spleen at levels around 105 CFU 1-week postimmunization (15). After RASV immunization, sufficient time and successful display of the antigen is needed for the development of a humoral response. Other studies have used type II and III secretion systems for RASV surface display of foreign antigens (41–44). Here, by cloning ecpABCD genes into the asd-based low copy vector pYA3337, E. coli chaperone EcpB and usher EcpC successfully displayed EcpA and EcpD on the surface of RASV χ9558(pYA4428). Using one plasmid to synthesize two different antigens and displaying them on the RASV surface is unique and could be used with other antigens for applications in biotechnology, microbiology, and vaccinology.

An immune response is a key component of an effective vaccine. As expected, vaccination with χ9558(pYA4428) elicited both anti-Salmonella LPS and anti-E. coli ECP antibodies in mice. Anti-EcpA antibodies were detected in mice vaccinated with χ9558(pYA4428) earlier than other treatments, which suggests inclusion of ECP in the RASV may elicit a faster immune response to some E. coli antigens. However, the ability of χ9558(pYA3337) to elicit anti-EcpA and -EcpD antibodies indicates cross-immunity between Salmonella and E. coli. There was a lack of evidence that anti-EcpA and -EcpD antibodies could bind to χ9558(pYA3337) based on Western blot and TEM. In addition, no reaction was observed when purified EcpA was probed with serum from χ9558(pYA3337). Previously, serum IgG cross-reactivity was demonstrated in RASV immunized mice against E. coli outer membrane proteins probably due to cross-reactivity of iron regulated outer membrane proteins (45), but to our knowledge, ECP or another homologous fimbria has not been reported in Salmonella. Anti-EcpA and -EcpD antibodies could be elicited by Salmonella antigens that share common conformational epitopes with ECP, which warrants future study.

Previously developed vaccines against ExPEC were tested mainly in BALB/c mice (36, 46–48); in this study, we evaluated our vaccines in both BALB/c and CBA/J mice. Slight differences in immune responses between mouse strains vaccinated with the same RASV could be due to a difference in Salmonella susceptibility. Contrary to BALB/c, CBA/J mice are considered more resistant to systemic infection with S. Typhimurium because these mice have a wild-type natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 allele conferring resistance to intracellular pathogens residing within vesicles (49). Furthermore, a higher median lethal dose is observed for CBA/J mice challenged with S. Typhimurium than BALB/c mice (50). However, a separate study showed both the spleen and liver are colonized by day 15 post-infection in CBA/J mice infected with S. Typhimurium strain 14028 (51). Because the parent S. Typhimurium strain χ3761 is more virulent than strain 14028 in mice (52), attenuated derivatives of χ3761 such as those used in this study should colonize internal organs as well, which explains elicitation of anti-Salmonella LPS IgG antibodies in the present study. LPS-specific antibodies were detected at 6 weeks but not 3 weeks postvaccination in BALB/c mice. These antibodies may have been elicited at 3 weeks postvaccination, but were not detected because they were in concentrations below the limit of detection in the ELISA. Previous studies have found no response or a low LPS-specific antibody titer in serum 2–3 weeks postvaccination with RASV strains (53, 54). However, by 6 weeks postvaccination LPS-specific antibodies were detected in these studies (53, 54). Mucosal IgA antibodies to LPS and ECP were also detected but only on day 41 in vaccinated BALB/c mice, which could not be compared to CBA/J mice at the same timepoint due to the UTI challenge timeline (Figure S2 in Supplementary Material).

Due to antigenic diversity of ExPEC strains, a vaccine should be designed to have broad protection. Previous studies have used O-antigen based vaccines against ExPEC serogroups commonly associated with human disease (5). One study used a tetravalent E. coli O-antigen vaccine to target serogroups O1, O2, O6, and O25 (55). Targeting specific O-groups based on prevalence in human patients is a rational approach, although it is limited to epidemiological evidence including region, as different countries may have different dominant serogroups (56). To assess protective potential of the RASV strains, in vitro assays were performed using multiple ExPEC serotypes and S. enterica serovars. Overall, mice vaccinated with χ9558(pYA4428) had the strongest inhibition of E. coli and Salmonella strains indicating inclusion of ECP may benefit broad protective ability. The mechanism of bacterial reduction in vaginal wash samples is unclear, but one proposed role of immunoglobulins in host defense includes antibodies binding to the bacterial surface and inhibiting its growth (57). Using an O1 specific monoclonal IgG antibody, Schauer et al. (58) found growth inhibition of Cronobacter turicensis after 2 h of incubation in an antibody concentration-dependent manner, independent of agglutination. A separate study found reduced growth of E. coli when incubated with IgY purified from egg yolk of White Leghorn hens immunized with formaldehyde-killed E. coli compared to IgY from unimmunized hens (59). RASVs eliciting elevated levels of anti-E. coli and Salmonella antibodies may have contributed to reduced bacterial levels in the in vitro assays. Other possibilities that may have accounted for differences in bacterial levels include transient differences in antimicrobial peptides in the samples collected, and reduced survival from complement-mediated effects instead of reduced bacterial growth. In addition, antibodies binding to pilus proteins may have caused agglutination of bacteria that was not detected in bacterial plating leading to an artificially low level in samples from immunized mice. Future studies could investigate the mechanisms responsible for the reduction in bacterial levels observed to determine whether these were biologically significant.

Recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccines can be delivered orally which make them easy to administer to those at risk for ExPEC infection such as adults >50 years old, patients undergoing genitourinary surgery, and residents of long-term healthcare facilities (5). Concerns have been raised over oral vaccines negatively impacting the microbiome (60). However, recent studies have shown vaccination with a live attenuated Salmonella strain or conserved E. coli antigens had no influence on the intestinal microbiome (61, 62). Herein, the vaginal wash assay showed that vaccination with the RASV delivering ECP had a differential effect on commensal E. coli, which indicates vaccination could inhibit some commensal E. coli commonly found in the vaginal tract, but may be replaced by other strains that are not affected, such as the E. coli Nissle 1917.

Vaccines against human ExPEC-associated diseases have been tested in murine models to evaluate ability to protect against infection (36, 46–48). Previously, we found EcpA and EcpD recombinant antigens elicited protection in a lethal BALB/c mouse sepsis model (14). A separate study used a similar approach to the current strategy by selecting YncE as a vaccine antigen, which is highly conserved in E. coli (63). This study found reduction, but not elimination, of E. coli in the blood and organs of mice following intravenous challenge with CFT073. In the current study using a mouse sepsis model, vaccination with χ9558(pYA3337) but not χ9558(pYA4428) reduced bacterial loads in the spleen compared with unvaccinated mice, but no significant differences were found in the blood or liver between treatments. The reason for the inability of χ9558(pYA4428) to provide strong protection against CFT073 could be due to a lack of ECP synthesis in CFT073 during challenge. In previous studies, we found different protection levels in mice challenged with CFT073 grown in different conditions, and different growth conditions yielded different ECP profiles (10, 14). For χ9558(pYA3337) immunization, Salmonella LPS and core antigens may have elicited antibodies that are providing protection. Anti-core LPS antibodies raised in mice have been reported to bind both E. coli and Salmonella strains (64). Structurally, all S. enterica serotypes except Arizonae have identical LPS core structures, and for E. coli five different known core structures exist (65). Similarities between Salmonella and E. coli LPS cores and the elicitation of anti-LPS antibodies from vaccination could account for reduced loads in χ9558(pYA3337) vaccinated mice. In addition, antibody titer against LPS was slightly elevated in χ9558(pYA3337) mouse serum at day 41 compared with χ9558(pYA4428) and may account for protection seen with χ9558(pYA3337) vaccination. Although a significant difference was found in the spleen of χ9558(pYA3337) immunized mice, an early endpoint was used in the sepsis challenge, which may not translate to significant improvements in survival. This endpoint was used to determine bacterial loads in internal organs based on previous studies (35, 36). Future studies could assess whether reductions in bacterial loads correspond to significant improvements in survival.

In addition to the mouse sepsis model, CBA/J mice were used to assess vaccine protection against UTI. Both RASV strains were effective in reducing bacterial loads in the bladders of vaccinated mice. Inclusion of ECP was also significant when analyzing the number of E. coli-positive bladder and liver samples. Since IgA antibodies were not detected in immunized mice, this protection could be conferred by a systemic immunity type response. The IgG response was similar between RASV strains, and may account for why a similar level of protection was observed between RASV immunizations. Also, RASV strains carry pathogen-associated molecular patterns (e.g., flagella and LPS) that induce innate immunity (66). Recently, Powell et al. (67) showed that RASV strains, including those derived from χ3761, elicit distinct innate immune responses in mice. In our study, induction of innate immune cells likely played a role in reducing severity of sepsis and UTI in RASV immunized mice compared with unvaccinated mice.

Interestingly, the in vitro assays showed that challenge strain CFT073 was significantly reduced compared with the unvaccinated group in vaginal wash samples but not in sera from χ9558(pYA4428) immunized mice. This parallels the significant difference found in the mouse UTI model and the lack of significant differences observed in the sepsis challenge. Contrary to CFT073, we found reduced levels of other ExPEC strains, including the multidrug resistant ExPEC strain JJ1886 in bacterial inhibition assays. Additional ExPEC strains could be assessed in the mouse sepsis model in future studies to determine whether RASV immunization can provide stronger protection against different ExPEC, specifically those of sequence type 131 which are disseminated globally (5).

In summary, we found ECP proteins can be synthesized using a single plasmid as surface antigens on a RASV strain. Both RASV strains elicited an antibody response in mice, although it was detectable sooner with χ9558(pYA4428) for some antigens. The results suggest that the RASV alone or containing ECP showed potential of bacterial inhibition as assessed in in vitro assays and provided protection against in vivo UTI in the bladder. Future studies should optimize the ExPEC antigens displayed by the RASV strain for a stronger immune response and enhanced protection against ExPEC infection.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Arizona State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The protocol (#1168R) was approved by the Arizona State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Six-week-old female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) and 4-week-old female CBA/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were obtained for infection experiments. Mice were acclimated for 7 days before experiments began. During the experiments, animals were monitored twice daily by our team, animal caretakers, and further inspected by a veterinarian.

Conceived and designed the experiments; performed the experiments: JM, ZS, and MM. Analyzed the data and reviewed and edited the manuscript: JM, ZS, RC, and MM. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: RC and MM. Wrote the paper: ZS and MM.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Ms. Jacquelyn Kilbourne, Ms. Natalie Mitchell, Ms. Kristen Morrow, Mr. Timothy Nam, and Ms. Alyssa Stacy for their technical help, Mr. Dave Lowry from Arizona State University for TEM sample preparation, and Dr. Jorge Girón from the University of Virginia for providing some of the E. coli antibodies used in this study.

This research was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R21 AI090416 to MM, US Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative USDA-NIFA-AFRI grant 2011-04413 to MM and RC, and Iowa State University start-up funding to MM. The funding sources had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01280/full#supplementary-material.

1. Marchetti A, Rossiter R. Economic burden of healthcare-associated infection in US acute care hospitals: societal perspective. J Med Econ (2013) 16:1399–404. doi:10.3111/13696998.2013.842922

2. Russo TA, Johnson JR. Medical and economic impact of extraintestinal infections due to Escherichia coli: focus on an increasingly important endemic problem. Microbes Infect (2003) 5:449–56. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00049-2

3. Jacobsen SM, Stickler DJ, Mobley HL, Shirtliff ME. Complicated catheter-associated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Clin Microbiol Rev (2008) 21:26–59. doi:10.1128/CMR.00019-07

4. Mellata M. Human and avian extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: infections, zoonotic risks, and antibiotic resistance trends. Foodborne Pathog Dis (2013) 10:916–32. doi:10.1089/fpd.2013.1533

5. Poolman JT, Wacker M. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli, a common human pathogen: challenges for vaccine development and progress in the field. J Infect Dis (2016) 213:6–13. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv429

6. Russo TA, Johnson JR. Extraintestinal isolates of Escherichia coli: identification and prospects for vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines (2006) 5:45–54. doi:10.1586/14760584.5.1.45

7. Ghunaim H, Abu-Madi MA, Kariyawasam S. Advances in vaccination against avian pathogenic Escherichia coli respiratory disease: potentials and limitations. Vet Microbiol (2014) 172:13–22. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.04.019

8. Garnett JA, Martínez-Santos VI, Saldaña Z, Pape T, Hawthorne W, Chan J, et al. Structural insights into the biogenesis and biofilm formation by the Escherichia coli common pilus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109:3950–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106733109

9. Rendón MA, Saldaña Z, Erdem AL, Monteiro-Neto V, Vázquez A, Kaper JB, et al. Commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli use a common pilus adherence factor for epithelial cell colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2007) 104:10637–42. doi:10.1073/pnas.0704104104

10. Stacy AK, Mitchell NM, Maddux JT, De la Cruz MA, Duran L, Giron JA, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence and production of Escherichia coli common pilus among avian pathogenic E. coli and its role in virulence. PLoS One (2014) 9:e86565. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086565

11. Avelino F, Saldana Z, Islam S, Monteiro-Neto V, Dall’Agnol M, Eslava CA, et al. The majority of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains produce the E. coli common pilus when adhering to cultured epithelial cells. Int J Med Microbiol (2010) 300:440–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.02.002

12. Martínez-Santos VI, Medrano-López A, Saldaña Z, Girón JA, Puente JL. Transcriptional regulation of the ecp operon by EcpR, IHF, and H-NS in attaching and effacing Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol (2012) 194:5020–33. doi:10.1128/JB.00915-12

13. Saldaña Z, De la Cruz MA, Carrillo-Casas EM, Durán L, Zhang Y, Hernández-Castro R, et al. Production of the Escherichia coli common pilus by uropathogenic E. coli is associated with adherence to HeLa and HTB-4 cells and invasion of mouse bladder urothelium. PLoS One (2014) 9:e101200. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101200

14. Mellata M, Mitchell NM, Schödel F, Curtiss R III, Pier GB. Novel vaccine antigen combinations elicit protective immune responses against Escherichia coli sepsis. Vaccine (2016) 34:656–62. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.014

15. Curtiss R III, Xin W, Li Y, Kong W, Wanda SY, Gunn B, et al. New technologies in using recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccine vectors. Crit Rev Immunol (2010) 30:255–70. doi:10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v30.i3.30

16. Tennant SM, Levine MM. Live attenuated vaccines for invasive Salmonella infections. Vaccine (2015) 33(Suppl 3):C36–41. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.029

17. Galen JE, Curtiss R III. The delicate balance in genetically engineering live vaccines. Vaccine (2014) 32:4376–85. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.026

18. Roland KL, Brenneman KE. Salmonella as a vaccine delivery vehicle. Expert Rev Vaccines (2013) 12:1033–45. doi:10.1586/14760584.2013.825454

19. Zhang S, Walters N, Cao L, Robison A, Yang X. Recombinant Salmonella vaccination technology and its application to human bacterial pathogens. Curr Pharm Biotechnol (2013) 14:209–19. doi:10.2174/1389201011314020011

20. Wang S, Kong Q, Curtiss R III. New technologies in developing recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccine vectors. Microb Pathog (2013) 58:17–28. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2012.10.006

21. Bollen WS, Gunn BM, Mo H, Lay MK, Curtiss R III. Presence of wild-type and attenuated Salmonella enterica strains in brain tissues following inoculation of mice by different routes. Infect Immun (2008) 76:3268–72. doi:10.1128/IAI.00244-08

22. Gunn BM, Wanda SY, Burshell D, Wang C, Curtiss R III. Construction of recombinant attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine vector strains for safety in newborn and infant mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol (2010) 17:354–62. doi:10.1128/CVI.00412-09

23. Kao JS, Stucker DM, Warren JW, Mobley HL. Pathogenicity island sequences of pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli CFT073 are associated with virulent uropathogenic strains. Infect Immun (1997) 65:2812–20.

24. Curtiss R III, Porter SB, Munson M, Tinge SA, Hassan JO, Gentry-Weeks C, et al. Nonrecombinant and recombinant avirulent Salmonella live vaccines for poultry. In: Blackenship LC, Bailey JS, Cox NA, Craven SE, Meinersmann RJ, Stern NJ, editors. Colonization Control of Human Bacterial Enteropathogens in Poultry. San Diego, CA: Academic Press Inc (1991). p. 169–98.

25. Santander J, Curtiss R III. Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi and Paratyphi A are avirulent in newborn and infant mice even when expressing virulence plasmid genes of Salmonella Typhimurium. J Infect Dev Ctries (2010) 4:723–31. doi:10.3855/jidc.1218

26. Galán JE, Nakayama K, Curtiss R III. Cloning and characterization of the asd gene of Salmonella typhimurium: use in stable maintenance of recombinant plasmids in Salmonella vaccine strains. Gene (1990) 94:29–35. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(90)90464-3

27. Byrd W, Cassels FJ. Long-term systemic and mucosal antibody responses measured in BALB/c mice following intranasal challenge with viable enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol (2006) 46:262–8. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2005.00039.x

28. Algasim A, Scheutz F, Zong Z, McNally A. Comparative genome analysis identifies few traits unique to the Escherichia coli ST131 H30Rx clade and extensive mosaicism at the capsule locus. BMC Genomics (2014) 15:830. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-830

29. Rasko DA, Rosovitz MJ, Myers GS, Mongodin EF, Fricke WF, Gajer P, et al. The pangenome structure of Escherichia coli: comparative genomic analysis of E. coli commensal and pathogenic isolates. J Bacteriol (2008) 190:6881–93. doi:10.1128/JB.00619-08

30. Yao Y, Xie Y, Kim KS. Genomic comparison of Escherichia coli K1 strains isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with meningitis. Infect Immun (2006) 74:2196–206. doi:10.1128/IAI.74.4.2196-2206.206

31. Welch RA, Dellinger EP, Minshew B, Falkow S. Haemolysin contributes to virulence of extra-intestinal E. coli infections. Nature (1981) 294:665–7. doi:10.1038/294665a0

32. Reister M, Hoffmeier K, Krezdorn N, Rotter B, Liang C, Rund S, et al. Complete genome sequence of the Gram-negative probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917. J Biotechnol (2014) 187:106–7. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.07.442

33. Torres-Escobar A, Juárez-Rodríguez MD, Gunn BM, Branger CG, Tinge SA, Curtiss R III. Fine-tuning synthesis of Yersinia pestis LcrV from runaway-like replication balanced-lethal plasmid in a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine induces protection against a lethal Y. pestis challenge in mice. Infect Immun (2010) 78:2529–43. doi:10.1128/IAI.00005-10

34. Johnson JR, Clermont O, Menard M, Kuskowski MA, Picard B, Denamur E. Experimental mouse lethality of Escherichia coli isolates, in relation to accessory traits, phylogenetic group, and ecological source. J Infect Dis (2006) 194:1141–50. doi:10.1086/507305

35. Smith SN, Hagan EC, Lane MC, Mobley HL. Dissemination and systemic colonization of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in a murine model of bacteremia. MBio (2010) 1:e00262–10. doi:10.1128/mBio.00262-10

36. Wieser A, Romann E, Magistro G, Hoffmann C, Nörenberg D, Weinert K, et al. A multiepitope subunit vaccine conveys protection against extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in mice. Infect Immun (2010) 78:3432–42. doi:10.1128/IAI.00174-10

37. Kalyoussef S, Nieves E, Dinerman E, Carpenter C, Shankar V, Oh J, et al. Lactobacillus proteins are associated with the bactericidal activity against E. coli of female genital tract secretions. PLoS One (2012) 7:e49506. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049506

38. Durant L, Metais A, Soulama-Mouze C, Genevard JM, Nassif X, Escaich S. Identification of candidates for a subunit vaccine against extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun (2007) 75:1916–25. doi:10.1128/IAI.01269-06

39. Thai KH, Thathireddy A, Hsieh MH. Transurethral induction of mouse urinary tract infection. J Vis Exp (2010) 42:2070. doi:10.3791/2070

40. Kramer U, Rizos K, Apfel H, Autenrieth IB, Lattemann CT. Autodisplay: development of an efficacious system for surface display of antigenic determinants in Salmonella vaccine strains. Infect Immun (2003) 71:1944–52. doi:10.1128/IAI.71.4.1944-1952.2003

41. Li Y, Wang S, Scarpellini G, Gunn B, Xin W, Wanda SY, et al. Evaluation of new generation Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccines with regulated delayed attenuation to induce immune responses against PspA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2009) 106:593–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811697106

42. Wang S, Li Y, Shi H, Sun W, Roland KL, Curtiss R III. Comparison of a regulated delayed antigen synthesis system with in vivo-inducible promoters for antigen delivery by live attenuated Salmonella vaccines. Infect Immun (2011) 79:937–49. doi:10.1128/IAI.00445-10

43. Kang HY, Srinivasan J, Curtiss R III. Immune responses to recombinant pneumococcal PspA antigen delivered by live attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine. Infect Immun (2002) 70:1739–49. doi:10.1128/IAI.70.4.1739-1749.2002

44. Juárez-Rodríguez MD, Arteaga-Cortés LT, Kader R, Curtiss R III, Clark-Curtiss JE. Live attenuated Salmonella vaccines against Mycobacterium tuberculosis with antigen delivery via the type III secretion system. Infect Immun (2012) 80:798–814. doi:10.1128/IAI.05525-11

45. Kong Q, Yang J, Liu Q, Alamuri P, Roland KL, Curtiss R III. Effect of deletion of genes involved in lipopolysaccharide core and O-antigen synthesis on virulence and immunogenicity of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun (2011) 79:4227–39. doi:10.1128/IAI.05398-11

46. Wieser A, Magistro G, Nörenberg D, Hoffmann C, Schubert S. First multi-epitope subunit vaccine against extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli delivered by a bacterial type-3 secretion system (T3SS). Int J Med Microbiol (2012) 302:10–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.09.012

47. Moriel DG, Bertoldi I, Spagnuolo A, Marchi S, Rosini R, Nesta B, et al. Identification of protective and broadly conserved vaccine antigens from the genome of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2010) 107:9072–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0915077107

48. Russo TA, Beanan JM, Olson R, Genagon SA, MacDonald U, Cope JJ, et al. A killed, genetically engineered derivative of a wild-type extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli strain is a vaccine candidate. Vaccine (2007) 25:3859–70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.100

49. Skamene E, Schurr E, Gros P. Infection genomics: Nramp1 as a major determinant of natural resistance to intracellular infections. Annu Rev Med (1998) 49:275–87. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.275

50. Hormaeche CE. Natural resistance to Salmonella typhimurium in different inbred mouse strains. Immunology (1979) 37:311–8.

51. Sivula CP, Bogomolnaya LM, Andrews-Polymenis HL. A comparison of cecal colonization of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium in white leghorn chicks and Salmonella-resistant mice. BMC Microbiol (2008) 8:182. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-8-182

52. Luo Y, Kong Q, Yang J, Mitra A, Golden G, Wanda SY, et al. Comparative genome analysis of the high pathogenicity Salmonella Typhimurium strain UK-1. PLoS One (2012) 7:e40645. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040645

53. Shi H, Wang S, Roland KL, Gunn BM, Curtiss R III. Immunogenicity of a live recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine expressing pspA in neonates and infant mice born from naïve and immunized mothers. Clin Vaccine Immunol (2010) 17:363–71. doi:10.1128/CVI.00413-09

54. Shi H, Wang S, Curtiss R III. Evaluation of regulated delayed attenuation strategies for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi vaccine vectors in nenatal and infant mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol (2013) 20:931–44. doi:10.1128/CVI.00003-13

55. van den Dobbelsteen GP, Faé KC, Serroyen J, van den Nieuwenhof IM, Braun M, Haeuptle MA, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a tetravalent E. coli O-antigen bioconjugate vaccine in animal models. Vaccine (2016) 34:4152–60. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.067

56. Ciesielczuk H, Jenkins C, Chattaway M, Doumith M, Hope R, Woodford N, et al. Trends in ExPEC serogroups in the UK and their significance. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (2016) 35:1661–6. doi:10.1007/s10096-016-2707-8

57. Roche AM, Richard AL, Rahkola JT, Janoff EN, Weiser JN. Antibody blocks acquisition of bacterial colonization through agglutination. Mucosal Immunol (2015) 8:176–85. doi:10.1038/mi.2014.55

58. Schauer K, Lehner A, Dietrich R, Kleinsteuber I, Canals R, Zurfluh K, et al. A Cronobacter turicensis O1 antigen-specific monoclonal antibody inhibits bacterial motility and entry into epithelial cells. Infect Immun (2015) 83:876–87. doi:10.1128/IAI.02211-14

59. Amaral JA, De Franco MT, Zapata-Quintanilla L, Carbonare SB. In vitro reactivity and growth inhibition of EPEC serotype O111 and STEC serotypes O111 and O157 by homologous and heterologous chicken egg yolk antibody. Vet Res Commun (2008) 32:281–90. doi:10.1007/s11259-007-9029-3

60. Ferreira RB, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Should the human microbiome be considered when developing vaccines? PLoS Pathog (2010) 6:e1001190. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001190

61. Eloe-Farosh EA, McArthur MA, Seekatz AM, Drabek EF, Rasko DA, Sztein MB, et al. Impact of oral typhoid vaccination on the human gut microbiota and correlations with S. Typhi-specific immunological responses. PLoS One (2013) 8:e62026. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062026

62. Hays MP, Ericsson AC, Yang Y, Hardwidge PR. Vaccinating with conserved Escherichia coli antigens does not alter the mouse intestinal microbiome. BMC Res Notes (2016) 9:401. doi:10.1186/s13104-016-2208-y

63. Moriel DG, Tan L, Goh KG, Phan MD, Ipe DS, Lo AW, et al. A novel protective vaccine antigen from the core Escherichia coli genome. mSphere (2016) 1:e00326–16. doi:10.1128/mSphere.00326-16

64. Di Padova FE, Brade H, Barclay GR, Poxton IR, Liehl E, Schuetze E, et al. A broadly cross-protective monoclonal antibody binding to Escherichia coli and Salmonella lipopolysaccharides. Infect Immun (1993) 61:3863–72.

65. Heinrichs DE, Monteiro MA, Perry MB, Whitfield C. The assembly system for the lipopolysaccharide R2 core-type of Escherichia coli is a hybrid of those found in Escherichia coli K-12 and Salmonella enterica. Structure and function of the R2 WaaK and WaaL homologs. J Biol Chem (1998) 273:8849–59. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.15.8849

66. Neutra MR, Kozlowski PA. Mucosal vaccines: the promise and the challenge. Nat Rev Immunol (2006) 6:148–58. doi:10.1038/nri1777

Keywords: vaccine, extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella, sepsis, urinary tract infection

Citation: Maddux JT, Stromberg ZR, Curtiss R III and Mellata M (2017) Evaluation of Recombinant Attenuated Salmonella Vaccine Strains for Broad Protection against Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Front. Immunol. 8:1280. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01280

Received: 09 May 2017; Accepted: 25 September 2017;

Published: 09 October 2017

Edited by:

Lee Mark Wetzler, Boston University School of Medicine, United StatesReviewed by:

Raffael Nachbagauer, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United StatesCopyright: © 2017 Maddux, Stromberg, Curtiss and Mellata. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Melha Mellata, bW1lbGxhdGFAaWFzdGF0ZS5lZHU=

†Present address: Jacob T. Maddux, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ, United States;

Roy Curtiss III, Department of Infectious Diseases and Pathology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.