There are a large number of people suffering from an organ or tissue loss due to injury, infection or disease. Although therapies like surgical reconstruction, transplantation or usage of prosthesis have saved and improved countless lives, they remain imperfect solutions due to occurrence of infection, chronic irritation, donor shortages, tissue rejection, and longer term complications such as development of malignant tumour. Although bone has an inherent ability to heal without leaving a scar, critical size defects fail to heal without intervention. The implantation of an engineered scaffold material with osteogenic cells seems to be a promising approach to achieve an optimal bone healing in critical-sized defects, since cell-mediated osteogenesis, especially at the centre of the defect, would be beneficial when combined with the osteoconductive effect of the bone graft material[1]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) isolated from various sources can be used for this purpose. The isolation of MSCs from dental tissues is easy, cost effective and does not raise additional safety and ethical concerns since they are obtained during regular orthodontic procedures. In this study, domestic pig was used as model organism for the isolation and transplantation of TGSCs due to its anatomical, physiologic, and metabolic similarities with humans. Bone structure and size are also important for the choice of pig to study bone tissue engineering. STRO-1 is a useful MSC marker that distinguishes only a subpopulation of MSCs that shows characteristics like high clonogenicity and multipotency differentiating to fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes[2].

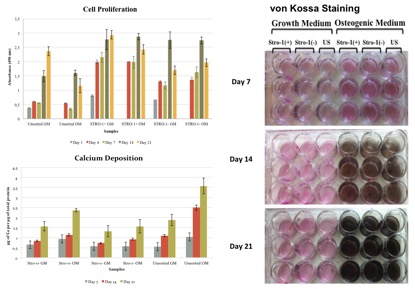

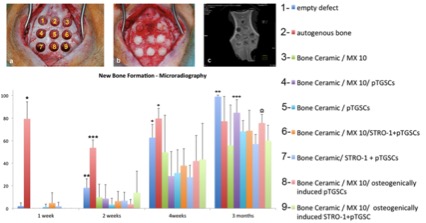

In this study, mandibular third molar tooth germs were surgically removed from the jaws of 6-month-old domestic pigs. Porcine TGSCs (PTGSCs) were isolated by explant culture technique after mincing the entire tooth germ tissue, including the dental mesenchyme and its surrounding follicle. PTGSCs were characterized by flow cytometry and by osteogenic, chondrogenic and adipogenic differentiation. Passage 3 PTGSCs were then tagged with STRO-1 antibody. Cells that express STRO-1 were sorted as STRO-1(+) cells and cells that do not express STRO-1 were sorted as STRO-1(-) cells by FACS Aria III. STRO-1 (+), STRO-1 (-) and unsorted cells were compared for their proliferation capacity by MTS assay and osteogenic differentiation capabilities in vitro by a quantitative calcium deposition assay and von Kossa staining. STRO-1 (+) and unsorted cells were also used for healing of critical-size bone calvarial defects of pigs in vivo with the use of a novel poly-ethylene glycol based hydrogel (PEG-hydrogel / MX10) and Bone Ceramic as scaffold.

According to in vitro studies, STRO-1(+) cells showed to be more clonogenic exhibiting higher proliferation rates compared to STRO-1(-) and unsorted cells, whereas unsorted cells performed better shown by calcium deposition and von Kossa staining when they were osteogenically induced indicating the importance of a heterogenous niche for their role in osteogenesis.

According to in vivo studies, novel PEG-hydrogel and Bone Ceramic was found to be an effective carrier for stem cell transplantation. Although transplantation of pTGSCs with PEG-hydrogel and Bone Ceramic facilitated the healing of defects, STRO-1(+) cells did not perform better than unsorted cells. Furthermore, in vivo studies also revealed the importance of osteogenic induction prior to implantation of cells to defects since osteogenically induced groups of either STRO-1(+) or unsorted cells led to increased bone density compared to non-induced groups.

PEG-hydrogel-Bone Ceramic combination and use of pTGSCs facilitated the healing of bone defect without any significant effect created by STRO-1(+) cells. Thus, STRO-1 sorting of pTGSCs is not an effective strategy to enhance the osteogenic capacity of TGSCs since they possibly perform their role when they are in interactions with other cells in a heterogenous niche.

International Team for Implantation (ITI), Basel, Switzerland; The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK), Ankara, Turkey

References:

[1] Niemeyer P., Szalay K., Luginbühl R., Südkamp N.P., Kasten P. Acta Biomater 2010;6:900-8.

[2] Dennis J.E., Carbillet J.P., Caplan A.I., Charbord P., Cells Tissues Organs 2002;170(2-3):73-82.